Abstract

This study seeks to understand how the COVID-19 outbreak impacted social work students completing field placements during the spring 2020 semester. In May 2020, a national survey was distributed soliciting information from MSW and BSW field students to examine their perspectives on their universities’ and field agencies’ responses to disruption of field education courses. The survey instrument consisted of seven open-ended questions pertaining to the potential impact COVID-19 had on students during their spring 2020–semester field placement, and the final question asked students to voluntarily submit a photo of their work space during the pandemic. Data were analyzed using QDA Miner. Analysis made use of open coding and directed coding using themes derived from the literature and the survey questions. Results revealed that while some field placement students received support, guidance, resources, and communication from their agencies and universities, many did not. Moreover, many students experienced unexpected ethical dilemmas and frustrations associated with the abrupt termination of relationships with clients. These findings are used to formulate policy recommendations for universities and field agencies regarding sudden transition to remote work during a pandemic-related shutdown.

Keywords: field education; ethical dilemmas; COVID-19; university policies; termination

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic (WHO, 2020). By the second week of April 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic prompted statewide lockdown orders in 48 states and the District of Colombia (Wu et al., 2020). Consequently, universities across the globe were compelled to devise plans for remote learning, as campuses were forced to close their doors to in-person learning. This left social work programs scrambling to devise a remote learning plan for social work students enrolled in field placement courses. On March 12, 2020, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) emailed social work programs soliciting information on how they were being affected by COVID-19 and its impact on field placements in particular, and asked for innovative ideas to minimize the impact on students completing their field education (CSWE, personal communication, March 12, 2020). CSWE subsequently announced field students needed only to complete 85% of the field hours required for field instruction.

With the abrupt change from working directly with clients to remote projects and teleservice contacts, field students had to adjust to these changes while dealing with the fallout from the pandemic. Many field students were now required to draw upon the concept of resiliency they learned about in their textbooks. For many students, it was another barrier among the many they had to overcome to complete their higher education goals.

The purpose of this phenomenological study is to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted social work students completing field placement in the spring of 2020. In May of 2020, bachelor’s- and master’s-level field students were contacted and asked to respond to a set of open-ended questions concerning their field placement during the COVID-19 lockdown. Respondents were recruited through listservs associated with six major national and state-level agencies responsible for overseeing field education programs. Subscribers to these listservs were asked to forward the link to our electronic questionnaire to their field students. A total of 219 respondents completed at least part of the questionnaire. Respondents were asked about support from their field agency, support from their university, access to necessary resources, and activities required of them for their field placements during the COVID-19 lockdown.

The findings from this study will help social work educators, field directors, and field placement agencies to understand the impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on social work students completing their field education courses. The study contributes to the small but growing body of literature and policies pertaining to social work placements during a public health emergency. Although, at the time of this writing, there is only one other published study that has captured empirically the experiences of social work field education students during the COVID-19 lockdown in the United States (Davis & Mirick, 2021), this study extends those findings to include a specific focus on how universities and agencies responded to the moment, and how they continued (or did not continue) to manage field education students and their academic requirements.

Literature Review:

Social Work and Social Work Education During Natural Disasters

Field education (FE) has long been known as the signature pedagogy of social work education (CSWE, 2015). FE requires any student within a CSWE-accredited program not only to master competencies through the classroom setting, but also to demonstrate their ability to perform, act, and think within the practice setting (CSWE, 2015). To facilitate the FE experience, social work degree programs must partner with various public and private community agencies, organizations, and corporations to fulfill the expectation of FE set forth by the CSWE.

In 2018, there were approximately 125,817 students enrolled in a CSWE BSW or MSW program (CSWE, 2019). To successfully complete their social work degree, all of these students are required to complete FE requirements during their academic career. While FE is a requirement of CSWE, to function properly FE depends on the willingness of community partners to allow social work students into their facilities to demonstrate their competencies. Providing students with a quality FE experience could potentially become jeopardized should students be barred from working with those public/private partners due to lack of willingness by the partners, or because of safety issues related to pandemics/epidemics or other natural disasters that may interrupt students’ abilities to work directly with those partners.

Since 2000, there have been three significant pandemic/epidemics documented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP, 2016). They include the 2002 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, also known as swine flu, and the 2019 COVID-19 pandemic, which is still occurring at the time of this writing. According to the CDCP (2012), an epidemic is an “increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area” (para. 3), while a pandemic is “an epidemic that has spread over several countries or continents, usually affecting a large number of people” (para. 3).

During a nine-month time span, from November 2002 to July 2003, there were a total of 8,098 people who contracted SARS across the globe, 774 of whom perished due to their illness. During this time, the United States saw only eight individuals who were diagnosed with SARS nationwide, and there were no reported SARS-related deaths (WHO, 2015). While the impact in the United States was minimal, the same cannot be said for China, which had 7,429 confirmed cases of SARS (WHO, 2015).

Approximately five years following the SARS outbreak, in 2009, the H1N1 pandemic began to take its course. H1N1 would move through more than 214 countries and result in 18,449 deaths across the globe (WHO, 2010). Unlike SARS, H1N1 would have a more significant impact in the United States, with 60.8 million confirmed cases and 12,469 deaths occurring between April 12, 2009 and April 10, 2010 (CDCP, 2014). Nearly ten years later, on February 26, 2020, the United States would have its first confirmed non-travel-related case of another deadly pandemic virus, COVID-19 (Jorden et al., 2020). Since that time, COVID-19 has spread to every state in the United States. As of September 7, 2021, more than 39 million cases have been confirmed and 644,848 individuals have died in the US (CDCP, 2021).

All three of these pandemics had a major impact on the social work profession and FE. Although the outbreaks varied in scope, they presented similar challenges for social work FE students in affected locations. Scholarly literature addressing the impacts on students revealed difficulties attempting to reconcile their desire to protect their own safety with their professional responsibilities. Students at times showed various levels of ambivalence when options to return to face-to-face interaction in FE resumed. While some students were eager to return (Ching-Man et al., 2004; Drolet et al., 2013; Gallagher & Schleyer, 2020), others had heightened concern about safety and potential exposure to the disease for themselves and for friends and family with whom they shared regular close contact (Ching-Man et al., 2004; Gallagher & Schleyer, 2020).

One study documented how some students were forbidden by their families to return to FE due to the risk of exposure to SARS (Ching-Man et al., 2004). Almost 17 years later, students would be faced with similar concerns regarding COVID-19. In a qualitative study by Gallagher & Schleyer (2020), one respondent stated, “How do I respond when my housemates…are uncomfortable with me being in the house because I might bring Covid home?” (p. 2).

This personal and professional conflict continued for students as they faced new ethical and moral dilemmas regarding providing care for their clients. SARS left students pondering questions such as, “But if you don’t do [field placement], the deprived groups will be left unattended” (Ching-Man et. al, 2004, p. 103). Respondents in the Gallagher and Schleyer (2020) study on FE students during COVID-19 echoed a similar quandary, with one respondent remarking that “it’s so hard as to be a student and not help when you feel morally and ethically inclined to do so” (p. 2). This conundrum was also expressed by social work field faculty studied by Phlean (2020), one of whom stated, “Some of our students want to continue their field placement and feel to abandon those agencies would not be the right thing to do professionally and ethically” (para. 22). A quantitative study completed by Drolet et al. (2013) examined the impact of the H1N1 pandemic on FE from the perspective of field directors and coordinators at twelve schools of social work in Canada. Their findings suggested that students placed in health care settings did not waiver in their commitment to their professional responsibilities, even when they became aware of increased risk of exposure to H1N1, and accepted additional work requirements, sometimes including vaccination (Drolet et al., 2013).

The length of interruptions in normal activities can vary during pandemics/epidemics, depending on the amount of time required to slow the rate of infection. However, other kinds of natural disasters may cause a different type of interruption. The disaster event may only last for minutes or days, though the aftermath can interrupt normal activity for a much longer period. For example, a year after Hurricane Katrina (HK), which resulted in approximately 80% of New Orleans being flooded, its population was still only half of what it had been when HK struck the city (Plyer, 2016). In 2005, when HK occurred, students pursuing BSW and MSW degrees in the affected regions were also impacted. Plummer et al. (2008), conducted a survey of 416 undergraduate and graduate social work students from four institutions that were impacted by HK and Hurricane Rita, focusing on volunteerism among the sample following the hurricanes. They found 56.7% (n = 236) of students surveyed struggled with feelings of guilt related to not being able to do more to help others.

This theme of students wrestling with their own needs while attempting to address the needs of others is also evident in the personal reflection of Boyer (2008), who states, “I had to be supportive, yet I was hurting too, for the same things, for the same reasons. I felt the pain my clients felt and it was excruciating” (p. 34). In a large national study of FE students’ experiences during the COVID-19 lockdown, Davis and Mirick (2021) also found that FE students expressed frustration, guilt, and regret regarding the need to abruptly terminate services to clients.

Plummer et al. (2008) found that 93.7% of students who elected to participate in the study engaged in some form of volunteering to assist victims of the hurricane despite being a victim of the hurricane themselves. This study also found that hurricane-related stressors were the strongest predictor of volunteerism related to hurricanes. In a personal reflection from a social work faculty member who was teaching in North Carolina at the time of Hurricane Florence, there were indicators of students’ willingness to volunteer in disaster relief efforts, and of the bond that developed among students as they assisted the community (Nguyen, 2020). Gallagher and Schleyer (2020) also found that medical students/residents were eager to volunteer when experiencing the COVID-19 epidemic; in a span of 10 minutes, residents filled a month’s worth of hospital volunteer slots.

The association between volunteerism and disaster has implications for the social work profession, including FE, where students may already be serving without monetary compensation. A recently published study by Davis and Mirick (2021) provides evidence that social work FE students view the social work profession as integral to a society’s capacity to respond to natural disasters such as COVID-19. Plummer et al. (2008) reported a moderate correlation between students who engaged in volunteer activities and an increase in their commitment to social work values. Similarly, Ching-Man et al. (2004), who completed a qualitative and quantitative study of social work students in Hong Kong during the SARS outbreak, found those who had a friend or family member contract SARS scored higher (p < .01) on questions related to positive life attitude in comparison to those who did not have similar direct exposure. Findings also revealed an increased level of devotion to the social work field (mean = 2.88) after the students experienced SARS (Ching-man et al., 2004). Nguyen (2020) reflected similar sentiments when he stated that “so many [students] indicate that the volunteering experience affirmed why they chose social work as a career” (p. 64).

While there are many parallels between SARS, H1N1, and COVID-19, COVID-19 represents the first time in modern history that the US has faced an abrupt, nationwide interruption in higher education, with more than 1,100 colleges and universities in all 50 states converting their face-to-face curriculum to an online format (Smalley, 2020). Other natural disasters, such as hurricanes, have halted higher education in specific areas for a more limited amount of time, but these do not compare to the magnitude of the COVID-19 interruption. The literature on social work practices during similar crises suggests that social work students and students in helping professions have struggled with balancing their personal and professional identity while attempting to recover from the crisis at hand, while also managing their desire to serve populations affected by the crisis within realities rife with risk and obstacles (Boyer, 2008; Ching-Man et al., 2004; Davis & Mirick, 2021; Gallagher & Schleyer, 2020). Students also leaned into opportunities to help others through volunteering, often resulting in an increased commitment to the field of social work (Ching-Man et al., 2004; Nguyen, 2020; Plummer et al., 2008).

Few studies, however, have examined FE students’ perspectives on how their academic institutions and field placement organizations prepared, responded, and supported them through the interruption in typical FE responsibilities and experiences. Although the extent of the damage, death, and disruption caused by COVID-19 are unprecedented in the postmodern globalized world, epidemiologists have warned for years that such a pandemic was likely, as humans have encroached into more natural systems with which they had not previously had contact, and have changed ecosystems in ways that may have negative human health outcomes (Myers et al., 2013). COVID-19 is the most recent pandemic, but it is not likely to be the last. Social work FE programs, agencies, and students should be prepared for similar circumstances in the future. This study makes use of an original dataset of 219 MSW and BSW students who were enrolled in FE courses during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, to examine the students’ perspectives on how their universities and field agencies responded to the sudden disruption of FE courses.

Data and Methods

Survey and Sample

In May of 2020, a survey of 15 questions was created using the SurveyMonkey platform (see Appendix 1 for questions as they appeared to respondents). The survey included seven open-ended questions concerning respondents’ field placements during the COVID-19 lockdown and five closed-ended demographic questions. The survey also requested that respondents upload a photograph of their current work environment during the lockdown. A link to the survey was sent to email listservs for the following agencies: the Association of Baccalaureate Social Work Program Directors; the National Association of Social Workers; the National Association of Social Workers, Ohio chapter; the National Association of Social Workers, Kentucky chapter; the Council on Social Work Education; and the North American Network of Field Educators and Directors. The email invitation asked field placement directors to forward the survey link to their bachelor’s- and master’s-level field students. Analysis began after a week of days with no new responses, in the first week of July, 2020. A total of 219 respondents completed the survey. The study was approved by the University Internal Review Board (IRB) Committee (IRB #S220-14). Respondents submitting photos completed an additional photography permission form, permitting use of their submitted photographs as part of the study and publications (Appendix 2).

Coding Procedures

Responses were first exported from SurveyMonkey into an Excel file, and then imported into QDA Miner, a qualitative data analysis software package. Coding was performed by the lead author. The coding strategy included a combination of both open and directed coding. Open coding is an inductive process that involves recognizing emergent themes in the data, while directed coding is a deductive process that involves identifying themes predetermined by the researcher, typically drawn from published literature and theory on the topic (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). In this study, directed codes were limited to “ambivalence about fulfilling responsibilities during a pandemic,” “ethical dilemmas,” and “emotional impacts,” all themes that have been identified in previous studies of FE during a natural disaster (Ching-Man et al., 2004; Gallagher & Schleyer, 2020; Phelan, 2020; Plummer et al. 2008). In addition, the qualitative questions included on the survey served as primary directed codes, because data segments generally followed patterns that reflected the questions asked. For example, one question asked respondents about resources that were unavailable to them during the COVID-19 lockdown, and responses to this question were limited to addressing unavailable resources. Therefore, “resources not available” served as a primary code in analysis. While the survey questions served as primary codes, a total of 147 secondary and tertiary codes were identified, resulting in a nested coding tree.

Reliability Analysis

Interrater reliability analysis was performed on a 10% sample of cases (22 cases) (see Hodson, 1999, p. 29). Interrater reliability and agreement analyses were limited to primary and secondary codes (see Campbell et al., 2013). Three independent coders coded the 10% sample of cases using the coding tree developed by the original coder. Among all three independent coders, a total of 403 codes were applied to the sample; of those 403 codes, 255 were identical codes applied to identical strands of text by all three coders, making the interrater reliability score 63.28%. After the interrater reliability analysis was performed, the three independent coders then met to attempt to resolve coding disagreements. The most frequent source of disagreement was on the application of the secondary code, “guidance” (under both the primary code “support from agency” and “support from university”), which one of the coders tended to interpret more narrowly than the other two. These disagreements were largely resolved through discussion. The final interrater agreement score for the 10% sample was 97.77%.

Results

Supports Received and Not Received from Agency

Students’ field placements were severely disrupted by the COVID-19 lockdown, and this typically meant altering several facets of their relationship with their field placement agency, including methods and frequency of communication, tasks assigned, and location of work, as many students were forced to work from home. Students sometimes had their field placements terminated entirely.

Through this disruption, agencies varied in the amount and type of support they provided to their field placement students. Here we define support as clear communication, direction, assistance, and flexibility in expectations and responsibilities. One respondent remarked, “I received a lot of direction and options to make me comfortable in regards to how to handle the crisis from the field agency.” Another respondent said, “My agency was really great about support and direction during the COVID 19. When it first began, we had lots of contact and was told what to do right away.” One BSW student commented that “my supervisor came up with some ideas on how I could complete my field hours from home but I was given the freedom to decide what I wanted to do.” Respondents also appreciated regular access to field supervisors via telephone, email, and videoconferencing, and support for students’ desires to change work hours and responsibilities.

Although many field students extolled the support received by their field placement agencies, a greater number expressed frustration with a lack of support from their agencies. While 5% of cases were coded as indicating a high degree of support from their agencies, 17.3% of cases were coded as indicating that they received very little support from their agencies.[1] One BSW student remarked that, with regard to support from her agency, there was “none—they went under quarantine and I was not allowed in the building, nor did I receive any at-home work.” Another MSW student remarked that she received “minimal direction. My placement agency was mostly reactive and delayed compared to the directives I received from my university/department of education.” One particularly frustrated MSW student described support from her agency in this way:

Trying to receive support was like pulling teeth. Nobody at my agency reached out to me or had any answers/direction when I finally reached out to them. I was never clear on the order of operations/chain of command so often I approached individuals out of order which caused unintended frictions. Ultimately, it led to a lot of wasted time.

Students who lamented a dearth of support from their agencies generally expressed frustration over lack of communication, unclear direction, confusion about tasks, and the absence of supervision. For example, one respondent said that “my supervisor and I met for supervision less frequently and they were mostly focused on signing off on my hours.”

Supports Received and Not Received from University

While the COVID-19 lockdown threw students’ relationships with their agencies into disarray, they also had to contend with the implications of those disruptions for completing their field courses for their universities. As with agencies, we observed substantial variation in the quality of support from professors, academic departments, and universities in general. However, our data suggest that students were a bit more satisfied with the support they received from universities compared to their agencies. While 11.8% of cases were coded as indicating a high degree of support from their universities, 6.8% of cases were coded as indicating that they received very little support from their universities. Students who expressed gratitude for the support they received from their universities largely discussed the flexibility their professors displayed by allowing them to complete alternative assignments in place of field hours. A BSW student said of her university, “The University was more than helpful and I do not think it would have been possible for me to graduate without their resources, such as trainings, research articles, and other activities related to social work. I cannot stress enough how helpful and understanding they were.” Another MSW student described the university’s flexibility in tasks this way:

There were a few field assignments given by [my institution’s] social work field office for students to complete. They were not tedious at all, and one assignment included a write-up to discuss personal thoughts on the pandemic and transitions that have had to be made. This assignment counted towards field hours, which was fair. There were also online module trainings to choose from that enhanced knowledge and understanding of social work, which students can take even after spring semester.

Another student commented on the flexibility her university displayed by allowing remote work to count toward field hours. She was given “options to remotely make up field hours in the event our placements closed or no longer were able to support interns. Support in the event a student did not feel comfortable going to their placement—the field director would help facilitate remote work or ending the placement and using supplemental hours.”

Students who expressed satisfaction with support received from their university also expressed satisfaction with guidance and direction received from their departments and professors. One BSW student said that she received “a lot” of support from her university. She goes on: “My social work professors were incredibly supportive and made sure to check in on us, as well as keep us updated. One of my professors became my new “field director” and has been great so far.” Other remarks, such as “guidance regarding ending with clients, how to complete field course requirements,” “emails regarding the situation, guidance on what to do,” and “answer [sic] to questions, guidance on the next steps to follow,” were typical.

Field placement students who were dissatisfied with the support received from their universities most often expressed frustration with insufficient guidance and communication, which often caused confusion. One first-year MSW student expressed her frustration thusly:

The university’s communication was minimal in regard to field placements. They communicated that classes would be held online after spring break, but did not immediately follow up regarding internships, leading to confusion and stress. There was mixed communication between faculty advisors and supervisors, leading my supervisor to ask me to come in more hours to try to get as many under my belt as possible when the pending announcement from the university was actually to remove interns immediately. The lack of direction was stressful. Additionally, my university was slow to act. There were LMFT interns at my field placement site from other universities who were all pulled from their internships before I was.

Another MSW student indicated mixed messages with regard to applying for a reduction in field hours. She said, “Direction was unclear regarding replacement assignments and applying for a reduction in field hours. Dean said no in official letter but 2 weeks later, assistant dean told us to apply.” Another student responded:

They sent conflicting information, overloaded our inboxes, ignored questions, got angry when we wanted results, and waited so long to give us alternate field assignments that I have been doing around 20 hours of my new assignment a week to complete. They were already problematic, but COVID-19 made it worse.

The above response alludes to another recurring theme with regard to lack of clear guidance: an overwhelming number of emails and instructions. While some universities were clearly remiss in their communications, others sent so many, often with conflicting information, that they caused consternation among students. One student lamented that “the university itself provided guidance … but all of the emails were a bit overwhelming.” Another MSW student interpreted the casual manner in which conflicting information was disseminated as disrespectful to students:

The communication from my school was disjointed, unhelpful, and frustrating. We as students kept hearing different things from the field office depending on who you spoke to and the time of day. It was frustrating because we felt like we were left out or being treated as first-year students when we are seniors and soon to be their colleagues with autonomy and opinions. The school seemed to be annoyed with us as a whole once they found out we were communicating and networking among ourselves and finding ways to take action and advocate for ourselves. But that is what our university has taught us.

By far, the most common failings in support from universities were inadequate communications and conflicting directives.

Online Trainings and Loss of On-the-Job Training

One common way that social work programs accommodated students who had their field placements terminated, or their hours reduced, was to provide students with opportunities to satisfy those hours with online training programs, such as continuing education units (CEUs), which document the completion of online trainings by awarding credit hours. One MSW student was relieved to be able to complete field hours with CEUs paid for by his university, but also noted that they paid for them only “reluctantly so.” Another MSW student noted that the online training programs funded by her university amounted to $800 per student, and expressed gratitude for this accommodation. However, some of the MSW students who completed field hours with online training courses were less satisfied with them as a substitution for the work experience that only a field placement can provide. One student observed that online work “cannot really replace on-the-job training.” Another student “felt the suspension of the experiential learning throughout the summer was not appropriate for graduate students.” Although provision of online alternatives to field hours is understandable for universities that needed to provide options for students to meet graduation requirements during an emergency lockdown, it is reasonable to assume that these students lost an important element of their professionalization that cannot be replaced by online trainings.

The Inability to Properly Terminate Client Relationships

Proper termination of services to clients is an integral component of ethical social work practice. According to section 1.17(b) of the NASW Code of Ethics (2017):

Social workers should take reasonable steps to avoid abandoning clients who are still in need of services. Social workers should withdraw services precipitously only under unusual circumstances, giving careful consideration to all factors in the situation and taking care to minimize possible adverse effects. Social workers should assist in making appropriate arrangements for continuation of services when necessary (para. 72 in “Ethical Standards”).

Indeed, abandonment is a form of malpractice, “which could lead to a lawsuit, a complaint to the state licensing board, or a request for professional review by the NASW Ethics Committee” (Felton & Polowy, 2019, para. 7). A sudden shelter-in-place order issued by a state government can reasonably be considered “unusual circumstances,” though the pervasive consternation and confusion that ensued often precluded “giving careful consideration to all factors in the situation and taking care to minimize possible adverse effects” for MSW and BSW students terminating services for clients in their field placements. Some common themes among respondents included frustration with an inability to properly terminate client relationships; grappling with the ethical dilemma of the need to keep oneself, loved ones, and clients safe during a public health emergency without abandoning clients; and the emotional toll such dilemmas wrought on students. When asked how COVID-19 affected their field placements, 10.7% of respondents spontaneously mentioned problems with termination of client relationships in their responses. One MSW student felt particularly burdened when her program failed to provide clear guidelines, and placed on her the onus of deciding whether or not to abruptly terminate client services:

COVID-19 started to impact on my community from the spring break. Since nobody was taking this crisis seriously in the beginning, it was hard to make [the] decision to come back to field after the break or not. At that time, my fellow students and I were very frustrated of missing clear leadership from our school liaison. While campus was closed and extending the emergency break for one more week, our program official asked social work students to make [their] own decision to go to field work or not. It caused extra emotional burden on students in the unprecedented time.

One BSW student also expressed some feelings of guilt concerning the abrupt termination of her placement in a public school: “I didn’t like it because I didn’t really get to get closure with my students. Since I was placed at a school, we didn’t know the Friday before will be our last time together.” Feelings of guilt, indeterminacy, and anxiety over abandonment pervade responses from students who were forced to abruptly terminate their client relationships due to the COVID-19 lockdown.

Resources: What Students Had, and What They Didn’t

For students who continued in their field placements, most were forced convert to videoconferencing with their agencies, field directors, and clients. This posed several challenges, including securing access to necessary resources in new, makeshift home offices. The most common resources to which students had access that were mentioned in responses were a laptop or computer (45.5% of respondents) and the internet (28.6% of respondents ).[2] Other commonly mentioned resources included access to a phone; videoconferencing platforms, such as Zoom and FaceTime; and continued access to agency resources. For example, one BSW student was grateful for access to “some clients numbers and emails,” while other students indicated they had continued access to agency-related online resources, such as OneDrive, SigmaCare, and other client websites. Only 2.7% of respondents spontaneously mentioned access to a confidential work space as a resource available to them during the COVID-19 lockdown.

While many students were able to access necessary resources in their transition to remote work, many also lacked necessary resources to properly continue in their field placements. However, relatively fewer students indicated that they lacked necessary resources, compared to those who indicated that they had necessary resources on hand. Moreover, the resources not available to students were much less concentrated into a few categories, compared to resources that were available. For example, while 45.5% of respondents spontaneously indicated access to a computer or laptop, no unavailable resource approached that percentage of respondents in our data. The most frequently occurring resources not available to students were agency resources (3.2% of respondents), and access to wireless internet (3.2% of respondents). Most unavailable resources had to do with access to technology, such as lack of a printer, scanner, reliable computer, software, or local telephone line (several respondents indicated that clients would not answer their calls because their cell number did not have a local area code). Informational resources were also relatively common among those resources indicated as not available, such as lack of access to client information, textbooks, and a library.

Although only two respondents spontaneously mentioned access to a confidential work space as a resource not available to them, several others mentioned lack of access to a work space or a desk (without explicitly referencing confidentiality issues), and one gender-nonbinary BSW student describes the challenges associated with continuing remotely in a field placement after being expelled from their dorm, and disowned by their family:

I was kicked out of university housing. So, I didn’t know where I was going. I couldn’t go “home” because my family disowned me. I ended up moving into the basement of my friend’s parent’s house. I did not, and do not, have a stable environment or sense of safety.

Although most respondents did not spontaneously indicate problems securing access to a safe and confidential living and working environment, this was clearly a problem for some of the students who were forced to suddenly leave the physical spaces of their universities and agencies.

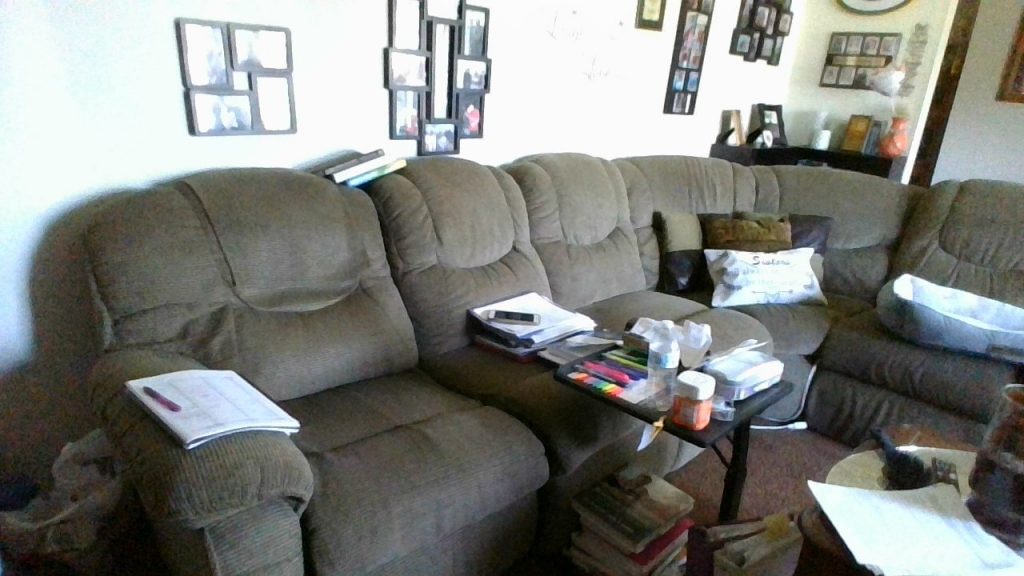

To illustrate further the challenges of transitioning to remote work for field placement students, we also asked respondents to upload an image of their current work environment. Images such as the one depicted in Figure 1 were common. Although this respondent did not explicitly reference lack of access to a confidential work space, the large, sectional couch suggests that it is a communal space, and raises questions about the ability to secure clients’ confidentiality while providing remote services. Figure 2 depicts another common theme among work space images submitted by respondents: cramped or sparse work spaces, often doubling as living rooms or sleeping quarters.

Figure 1

Student Remote Work Space in Living Area

Note: Photo of remote work space uploaded with questionnaire. Although we cannot say for sure that this is not a confidential work space, the large, sectional couch suggests that this is a communal space.

Figure 2

Student Remote Work Space in Bedding Area

Note: Photo of remote work space uploaded with questionnaire. Images of cramped work spaces, often doubling as living rooms or sleeping quarters, were common among respondents who uploaded images of their work environment.

Discussion

The sudden transition to remote work and learning severely disrupted many dimensions of social and economic life for businesses, social service agencies, and institutions of higher education across the country. Social work students who were in the process of completing their practicum requirements during this time likewise found themselves amidst confusion, as their university programs and placement agencies scrambled to adjust to the new reality. While many of the respondents in this study expressed satisfaction with their agencies’ and universities’ responses, our analysis also revealed that poor communication, confusion over changing expectations, and lack of access to necessary resources, including a confidential work space, were recurring themes. Respondents who were instructed to substitute other trainings or assignments for field hours also lamented the loss of on-the-job experience, and the inability to properly terminate services with clients.

Many of the results presented here echo findings of previous studies of how natural disasters may affect social work field placement students. Frustration with an inability to properly terminate client relationships (Ching-Man et al., 2004; Gallagher & Schleyer, 2020; Phelan, 2020); grappling with the ethical dilemma of the need to keep oneself, loved ones, and clients safe during a public health emergency without abandoning clients (Ching-Man et al., 2004; Gallagher & Schleyer, 2020); and the emotional toll such dilemmas wrought on students (Davis & Mirick, 2021; Plummer et al., 2008) were recurring themes among respondents of this study. Social work is a deliberately empathetic profession, and the NASW code of ethics impels social workers to make clients the highest priority by fostering trust, obtaining informed consent when using technologies to provide services, protecting clients’ confidentiality, and formally terminating services when they are no longer required (NASW, 2017). However, natural disasters, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and the corresponding disruptions to social and economic life such disasters induce, can make meeting those standards especially challenging, if not impossible in some cases. While natural disasters can inspire renewed commitment to community service (Gallagher & Schleyer, 2020; Nguyen, 2020; Plummer et al., 2008), they can also create substantial obstacles to delivering those services.

Although COVID-19 has often been referred to as a “once-in-a-century pandemic” (Gates, 2020), epidemiologists have warned for years that such a pandemic was likely, as humans have encroached into more and more natural systems with which they had no previous contact, and have changed ecosystems in ways that may have negative human health outcomes (Myers et al., 2013). Even if an increasingly vaccinated population makes another COVID-19 lockdown unlikely, it is possible that there could be future pandemic-related lockdowns that may affect practicums. Therefore, it is imperative that social work programs and field placement agencies develop clear policies for such circumstances.

University and Agency Policies

Field students reported confusion and a lack of resources from their universities and/or field sites. Our findings reiterate the importance of clear guidance and frequent communication. However, this communication must be strategic, thorough, and, most importantly, send a unified message from the program. As students reported receiving conflicting information from various faculty and administrators within the program, social work programs are encouraged to devise a state-of-emergency communications plan specific to field education. The COVID-19 shutdown forced programs to create a reactive response to the pandemic; however, hindsight now provides programs a clear path of “lessons learned” to create a proactive response to devising a rapid response communication plan.

As programs permitted the use of online trainings and webinars to count towards field hours, students were often faced with financial barriers when trying to access online training platforms. As such, it would behoove the profession as a whole to devise pathways for field students, during state of emergency/public health crises, to access online training platforms at a reduced or prorated rate to accommodate financial disruption and hardship.

Ethical Dilemmas

Results of this study suggest that many students did not have the opportunity to terminate services with their clients. It was often reported that students were told, without warning, that they were not able to return to their field site. Without access to agency resources such as databases, students were unable to conduct any type of termination, let alone communication, with their clients. As a result, assignments and online trainings were substituted with no follow-up plan developed to terminate with clients. Consequently, programs reactively contributed to engaging in unethical termination practices. Therefore, the COVID-19 shutdown can potentially serve as a learning experience for programs regarding how to prepare proactively for ethical termination practices during a state of emergency, including developing policies, revising curriculum, and ensuring confidential work spaces for students.

Programs are encouraged to consider how to address termination procedures should a national shutdown or state of emergency prevent students from returning to their field placement sites. Programs should consider starting these conversations with their field sites by creating work groups to develop a response and/or utilizing the social work advisory boards to devise ethical termination procedures during a shutdown. Such procedures should be included in the learning contracts or memoranda of understanding, so that there is a clear pathway for students to access client data and agency resources while working from remote locations.

The COVID-19 national shutdown provided many examples of ethical dilemmas faced by social workers and social work students. This presents an opportunity for programs to revise the ethics curriculum to include “safety verses responsibility” considerations in social work practice. The purpose here is to prepare students for critical thinking on this issue. Such discussions will also serve to prepare students mentally to address ethical issues of termination when faced with a state of emergency or pandemic. Numerous studies, including this one, highlight students’ moral struggles when they are unable to terminate with clients when natural disasters and other public health crises interrupt service delivery.

Finally, photos submitted by field students during this study highlight students’ inability to access confidential work spaces when providing remote teleservices. Students often shared work spaces with roommates and laptops with family members, and many did not have the ability to work within confidential spaces when providing remote teleservices to clients. As such, field instructors should incorporate either discussions or assignments to assist students to develop a confidential work space plan, should students need to provide remote services to clients.

Although this study provides important insights into the experiences of FE students during the COVID-19 lockdown, it does have limitations. Responses to open-ended questions were typed into the SurveyMonkey platform, which did not permit researchers to ask follow-up questions. Moreover, responses were often short, sometimes just a few words. Semistructured interviews would have provided richer data. There were no identified implications when surveys were not completed in their entirety. The most commonly omitted response was the invitation to upload a photograph of the respondent’s work space. Future studies of how natural disasters affect social work students’ field placements should make use of qualitative interviewing techniques. Also, because this is a qualitative study of students’ experiences, it cannot provide information about the proportion of universities and agencies that provided clear guidance and access to resources to field students, or the proportion of students within each university and agency who were satisfied with their responses to the COVID-19 lockdown.

Future research in this area might develop a metric to operationalize the quality of universities’ and agencies’ responses in a natural disaster. Furthermore, as the national shutdown caused the abrupt shutdown of field placements, we suggest future research be conducted on client outcomes after abrupt termination with field students. Longitudinal studies could assess the long-term effects on client outcomes due to abrupt termination of services from FE students, which could include trust versus mistrust of working with students, follow-through with services post-COVID, and the impact of teletherapy/teleservice on client outcomes. Finally, MSW and BSW programs may have systematic differences in their capacities to respond to a disaster situation, including differences in the types of resources and supports offered to field students. The authors of this study plan to conduct further data analysis on survey results to explore if any trends are evident in the responses of BSW students versus MSW students.

References

Boyer, E. (2008). A student social worker’s reflection on the self and professional identity following the impact of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans. Traumatology, 14(4), 32–37.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608325296

Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J., & Pedersen, O. K. (2013). Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(3), 294–320.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113500475

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, May 18). Principles of epidemiology in public health practice, third edition: An introduction to applied epidemiology and biostatistics. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section11.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, June 24). H1N1 flu. https://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/estimates_2009_h1n1.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, June 27). CDC timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 7). COVID data tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

Ching-Man, L., Hung, W., & Terry, L. (2004). Impacts of SARS crisis on social work students: Reflection on social work education. The Hong Kong Journal of Social Work, 38(1/2), 93–108.

https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219246204000075

Council on Social Work Education. (2015). 2015 educational policy and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs.

https://www.cswe.org/getmedia/23a35a39-78c7-453f-b805-b67f1dca2ee5/2015-epas-and-glossary.pdf

Council on Social Work Education. (2019). 2018 statistics on social work education in the United States.

https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/d778d922-bf29-49c4-bef0-28873937f41f/2018-statistics-on-social-work-education-in-the-united-states-ver-2.pdf/

Davis, A., & Mirick, R. G. (2021). COVID-19 and social work field education: A descriptive study of students’ experiences. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), 120–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1929621

Drolet, J., Ayala, J., Pierce, J., Giasson, F., & Kang, L. (2013). Influenza “A” H1N1 pandemic planning and response: The roles of Canadian social work field directors and coordinators. Canadian Social Work Review, 30(1), 49–63.

Felton, E. M., & Polowy, C. I. (2019). Termination: Ending the therapeutic relationship-avoiding abandonment. National Association of Social Workers California News.

https://naswcanews.org/termination-ending-the-therapeutic-relationship-avoiding-abandonment/

Gallagher T. H., & Schleyer A. M. (2020). We signed up for this: Student and trainee responses to the Covid‐19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(25), e96(1)–e96(3).

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005234

Gates, B. (2020). Responding to Covid-19—A once-in-a-century pandemic? New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 1677–1679.

http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2003762

Hodson, R. (1999). Analyzing documentary accounts. Sage.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jorden, M. A., Rudman, S. L., Villarino, E., Hoferka, S., Patel, M. T., Bemis, K., Simmons, C. R., Jespersen, M., Johnson, J. I., Mytty, E., Arends, K. D., Henderson, J. J., Mathes, R. W., Weng, C. X., Duchin, J., Lenahan, J., Close, N., Bedford, T., Boeckh, M., …Starita, L. M. (2020). Evidence for limited early spread of COVID-19 within the United States, January–February 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(22), 680–684.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6922e1

Myers, S. S., Gaffikin, L., Golden, C. D., Ostfeld, R. S., Redford, K. H., Ricketts, T. H., Turner, W. R., & Osofsky, S. A. (2013). Human health impacts of ecosystem alteration. Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(47), 18753–18760.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1218656110

National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Read the code of ethics.

https://www.social workers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

Nguyen, P., V. (2020). Social work education and Hurricane Florence. Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping, 26(1), 61–67.

https://reflectionsnarrativesofprofessionalhelping.org/index.php/Reflections/article/view/1723

Phelan, M. T. (2020, March 31). Clinical placements adapt to COVID-19 crisis. UMB News.

https://www.umaryland.edu/news/archived-news/march-2020/newspressreleaseshottopics/clinical-placements-adapt-to-covid-19-crisis.php

Plummer, C. A., Ai, A. L., Lemieux, C. M., Richardson, R., Dey, S., Taylor, P., Spence, S., & Kim, H.-J. (2008). Volunteerism among social work students during hurricanes Katrina and Rita: A report from the disaster area. Journal of Social Service Research, 34(3), 55–71.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01488370802086328

Plyer, A. (2016, August 26). Facts for features: Katrina impact. The Data Center.

https://www.datacenterresearch.org/data-resources/katrina/facts-for-impact/

Smalley, A. (2020, July 7). Higher education responses to coronavirus. National Conference of State Legislatures.

https://www.ncsl.org/research/education/higher-education-responses-to-coronavirus-covid-19.aspx

World Health Organization. (2010). Pandemic (H1N1) 2009—update 112.

https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2010_08_06-en

World Health Organization. (2015). Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO timeline—COVID 19. 27 April 2020 statement.

https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19

Wu, J. Smith, S., Khurana, M., Siemaszko, C., & DeJesus-Banos, B. (2020, March 25). Stay-at-home orders across the country: What each state is doing—or not doing—amid widespread coronavirus lockdowns. NBC News.

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/here-are-stay-home-orders-across-country-n1168736

Appendix 1

Survey Questions

Open-ended Questions:

1. What support or direction did you receive from your field agency during the COVID 19 crisis?

2. What support or direction did you receive from your university during the COVID 19 crisis?

3. What self-care measures did you take during the COVID 19 crisis? If you did not take self-care measures, discuss why or why not.

4. How has the COVID 19 crisis impacted your field placement?

5. Did you have to complete remote activities due to COVID 19?

a. If no, why?

b. If yes, did you have the resources to complete remote activities from home?

6. What resources did you need, that you had, for your remote work?

7. What resources did you need, that you did not have, for your remote work?

Demographic Questions:

1. What semester of field are you in as defind by your university?

2. Are you in an MSW or BSW program?

a. BSW

b. MSW

3. Gender (open ended):

___________

4. Class standing:

a. Undergraduate, senior

b. Undergraduate, junior

c. Graduate student, advanced standing

d. Graduate student, standard program

5. What type of field site?

a. Child Welfare

b. Colleges & Universities

c. Government Agencies

d. Health Clinics and Outpatient Care Settings

e. Hospice & Palliative Care

f. Hospitals & Medical Centers

g. Mental Health Clinics & Outpatient Facilities

h. Private Practice

i. Psychiatric Hospitals

j. Schools (K-12)

k. Social Services Agencies

l. Corrections

Appendix 2

Informed Consent for Photograph Upload

We would like you to upload a photograph of your remote work station you are using for your field placement.

By submitting a photograph of your remote work station, you give permission to Understanding the Impact of the COVID 19 Pandemic on Social Work Field Placements: A Student’s Perspective to use my photographic likeness of my remote work station in connection with my field placement in the connection with the COVID 19 remote work field requirements, in all forms and media for publications, presentations, and any other lawful purposes.

Check One:

___I give permission to share my photograph

___I do not give my permission to share my photograph

[People who indicate they do not give permission to upload a photograph, will not be given the option to upload a photograph and will be taken to the end of the survey.]

[1] While many respondents commented on specific supports received or not received, these percentages refer to respondents who commented specifically on the overall quality of support from their field placement agencies.

[2] This does not necessarily indicate that only 45.5% of cases had access to a computer, or that 28.6% of cases had access to the internet. It indicates the percentage of respondents who spontaneously mentioned those items when asked which resources were available to them for their field placement work during the COVID lockdown.