Abstract

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Council on Social Work Education modified field education delivery methods and reduced the number of required field hours. Consequently, schools of social work and field agencies employed online and other methods of distance learning to fulfill field education requirements. This scoping review synthesizes available literature on social work pedagogical approaches to field education during the COVID-19 pandemic, identifies knowledge gaps in the literature for future studies, and suggests the need for proactive disaster preparation for future field challenges. Eleven peer-reviewed articles are included in this review. We describe the challenges and achievements experienced by schools of social work, students, and field supervisors. Findings indicated five themes: (a) remote field work, (b) alternate activities, (c) communication, (d) technology, and (e) early termination with clients. Suggestions illuminate implications for best-practice scenarios to promote future disaster preparedness.

Keywords: social work; social work pedagogy; field education; COVID-19

According to the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), field education is the signature pedagogy of the social work profession (CSWE, 2015). It is in this learning environment that social work students employ ethical codes and practice social justice. Field instruction instills the foundation for practicing competent social work, and gives students empirical opportunities to apply social work practice knowledge while upholding the professions’ values and ethical standards (Azman, 2021). The structural foundation of field education was explicated in 2008 in the CSWE’s Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards manual, and was upheld in its later versions in 2015 and 2022 (CSWE, 2015, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic presented substantial challenges to the standard CSWE field education requirements. By April of 2020, the health crisis led to 45 states implementing restrictions that resulted in greatly reduced human contact and fostered homebound lifestyles (Mevosh et al., 2020). The concepts and principles of traditional in-person delivery of field services were challenged and modifications in service allocation became necessary. As a result, the CSWE issued an addendum modifying field education requirements and reducing required field hours for baccalaureate students from the previously mandated 400 hours to 345 hours, and from 900 hours to 765 hours for master’s-level students (CSWE, 2020).

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, field programs were challenged with surmounting obstacles to positive, productive internship experiences. The very idea of social work students in the field doing 400 or 900 hours of unpaid work for social work field agencies has been considered by some to be oppressive and fraught with numerous challenges related to human rights, social justice, and student well-being. Researchers suggest field placement financial burdens—including vehicle-related costs, reduced time for wage-earning employment, and childcare expenses—have resulted in stress on the family system and on the meeting of basic needs (Smith et al., 2021). In some instances, when students are trying to manage parental responsibilities and employment requirements, field supervisors have noted student learning deficits (Hemy et al., 2016). Field supervisors have indicated that the lack of available staff, heavy caseloads, and overall occupational demands detract from their ability to supervise effectively (Domakin, 2015; Hill et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, despite the issues surrounding it, field education has remained a required and vital component of social work education, and continues to be considered the signature pedagogy of the profession. Historically strained by both limited resources and available placements, field education has been further challenged by a lack of field supervisor retention, the financial constraints faced by educational institutions and social service agencies, and a deficiency in the number of adequate supervisors (Ayala et al., 2018; Dempsey et al., 2022; Gushwa & Harriman, 2019). Within this context, there has been an increase in agencies rejecting student workers due to high caseloads, creating time constraints that do not allow for field supervisors to provide free supervision, and thus disabling the ability to fulfill student needs (Ayala et al., 2018). The challenges already present were further stressed by the pandemic in unforeseen ways. Schools of social work and field agencies alike were unprepared to cope with the challenges of online social work training or practice (Melero et al., 2021).

Due to the nature of the pandemic and the need to ensure student, faculty, and client safety, field education reforms had to materialize quickly. Contingency plans and revised learning platforms were implemented to fulfill student field needs and accommodate distance learning (Crocetto, 2021; Dempsey et al., 2022; Mitchell et al., 2022; Szczgiel & Emery-Fertitta, 2021). While some literature reflected on the innovative methods developed in response to COVID-19 (Crocetto, 2021; Dempsey et al., 2022; Jun et al., 2021; Melero et al., 2021; Mirik & Davis, 2021; Mitchell et al., 2022; Perone, 2021), other research addressed student, faculty, or field supervisor experiences (Bloomberg et al., 2022; Davis & Mirick, 2021; Szczgiel & Emery-Fertitta, 2021).

To date, a review of published literature researching or reflecting on social work field modifications in response to the pandemic has not been undertaken. We conducted a scoping review to summarize available literature, identify knowledge gaps for future studies, and illuminate the implications for social work (Tricco et al., 2018). The focus of this review is to describe how social work programs addressed field education modifications during the pandemic. Additionally, we consider how schools of social work, field supervisors, and students responded to changes in field education implementation. Knowledge gained from changes forced by the pandemic can provide awareness of effective online pedagogical strategies. Importantly, findings can be used to guide practical and strategical approaches in the event of future disasters (Crisp et al., 2021).

Methods

Protocol and Registration

This scoping review was conducted following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (McGowan et al., 2020). A literature search was conducted by a five-member scoping review team on March 14, 2022. The review was guided by the following research questions: (a) How have social work programs addressed field education during COVID-19? and (b) How have schools of social work, field supervisors, and students responded to modifications made to field education due to COVID-19?

In addition to a hand search, the databases Psych INFO, MEDLINE, Ebscohost Academic Collection, Social Work Abstracts, Soc INDEX with Full Text, and CINAHL Complete were searched for qualitative and quantitative peer-reviewed articles published between January 2020 and January 2022. Grey literature and dissertations were not incorporated in the search. The Boolean search strategy used the following search terms: (a) “social work field education” or “social work field placement”; (b) “United States” or “America” or “USA” or “U.S.” or “United States of America”; and (c) “COVID-19” or “Coronavirus” or “2019-nCoV” or “SARS-CoV-2” or “CoV-19.” Additional inclusion criteria required selected literature to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, available in the English language, and include the impact of COVID-19 on Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) and/or Master of Social Work (MSW) students. Exclusion criteria included: (a) articles not published in a peer-reviewed journal; (b) articles published in a language other than English; (c) review articles; (d) dissertations; and (e) letters to the editor.

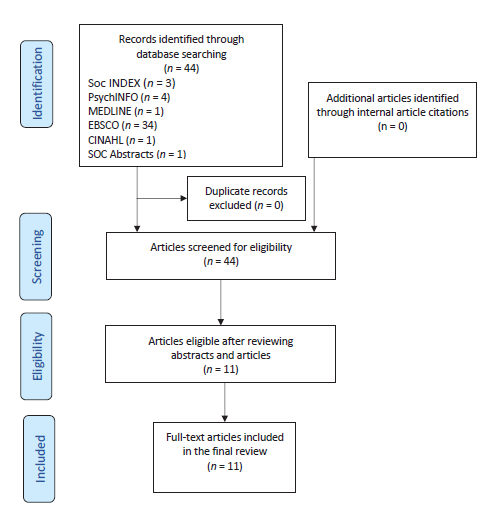

The initial search produced 44 articles with no duplicates. Three articles were found in Soc INDEX (n = 3), four articles were found in PsychINFO (n = 4), one article was found in MEDLINE (n = 1), 34 articles were found in EBSCO (n = 34), one article was found in CINAHL (n = 1), and one article was found in SOC Abstracts (n = 1) resulting in a total of 44 articles (N = 44). No additional articles were identified from article citations as meeting the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1

Review and Selection of Articles

All five members of the research team independently conducted an abstract review of the 44 articles and identified 11 articles which met the criteria for a full-text review. All articles (n = 11) that met the inclusion criteria were selected for the scoping review (see Figure 1). The selected articles were independently reviewed by the research team for agreement on inclusion criteria using a data abstraction form to summarize findings from each study. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and collaborative consensus was achieved. The researchers used the data extraction form to code the author, year of publication, location of the study, purpose, study design, sample size and gender, and study outcomes from the 11 eligible articles. The Zoom platform was used to collaborate while planning and conducting the scoping review.

The selected literature collected data from a range of participants and used a variety of data collection methods, including national surveys, weekly student survey responses, and program analytics. Table 1 provides a summary of the important characteristics of each study, including author(s) and date of publication, study setting, study design, sample demographics, method of data analyses, and study outcomes.

Table 1

Summary of Article Selections

| Author/ Year | Purpose | Study design | Region | Data analysis | Population | N | Female (%) | Study outcomes |

| Bloomberg et al., 2022 | Describe students’ reflections on home lives, school experiences, field placements, mental health challenges, feelings of burnout, complexities of racial disparities and injustices, and coping mechanisms | Personal reflection | New York | — | MSW students | 1 | — | Provided insight into varied experiences during pandemic; pathways toward resiliency |

| Crocetto, 2021 | Summarize field program’s innovative response to COVID-19 pandemic | Brief note | Pennsylvania | — | — | 1 | — | Provided reflections on project’s implementation, insights gained, and plans to sustain new field initiatives |

| Davis & Mirick, 2021 | Describe students’ perspectives on field placement continuation, modification, or suspension | Mixed methods | Nationwide | Descriptive statistics & thematic analysis | BSW & MSW students | 1,522 | 84.95% | Discussed students’ experiences with remote service delivery, abrupt terminations, role of social work in an unprecedented crisis, and implications for social work education |

| Dempsey et al., 2022 | Examine the steps taken by the field faculty/ department to address placement process in field education | Case study | New York | — | Field faculty, department | 1 | — | Discussed field disruptions, continuity of learning, contingency plans, anxiety caused by COVID-19, and lessons learned |

| Jun et al., 2021 | Explore students’ and field instructors’ perceptions of effective teaching practices during online instruction | Mixed methods | Midwestern United States | Descriptive statistics & content analysis | Students & field instructors | 65 | 82.5% | |

| Melero et al., 2021 | Describe the response of a field education department to COVID-19 | Field note | California | — | Described lessons learned, recommendations for social work curriculum, online social services, and future research | |||

| Mirick & Davis, 2021 | Describe students’ perspectives to online courses, and field modification or termination | Mixed methods | Nationwide | Descriptive statistics & thematic analysis | MSW & BSW students | 1,522 | 84.95% | Increased student needs, perceptions of programmatic responses in terms of academic and social support, and recommendations for crisis response |

| Mitchell et al., 2022 | Delineate program redesign for oncology social work interns at a cancer center using remote/virtual modalities | Case study | New York | — | Social work interns | 1 | — | Described an innovative programming model for health care settings |

| Morris et al., 2020 | Describe a case study on project to reduce isolation among older adults and provide an alternative model to field work | Case study | New York | — | MSW students, community companions | 7 | — | Described student-initiated field education project to decrease social isolation and contribute to action learning projects for social work field education |

| Perone et al., 2021 | Explore students’ concerns, attitudes, and perceptions about online instruction, virtual field placement, and innovations | Mixed methods | Michigan | Descriptive statistics, comparative analysis, & reflections | Social work students | 75 | 86.67% | Discussed lessons learned about assignments, context, agency, mental health support, and equity; student recommendations on education and training |

| Szcygiel & Emery-Fertitta, 2021 | Provide literature review on concepts of forced field termination, parallel process, and shared trauma | Literature review | — | — | — | — | Provided literature review and insights on forced termination |

Results

One of the selected articles was published in 2020 (Morris et al., 2020) and all other articles (n = 10) were published in 2021. The majority of the studies (n = 7) were based in the northeast or midwestern United States, with only one study (n = 1) based in California and two (n = 2) that collected data nationwide. The majority of the studies (n = 7) collected data from BSW and/or MSW students, with two (n = 2) collecting data from field faculty and field instructors, and two (n = 2) not collecting original data. Four studies (n = 4) used a mixed methods research design, three (n = 3) were case studies, two (n = 2) were field notes, and one (n = 1) was a literature review.

The 11 articles selected for review addressed pedagogical approaches to field education during the COVID-19 crisis through the perspectives of students, field instructor faculty, agency field supervisors, schools of social work, or a combination of participant voices. Three of the 11 articles were case studies. Of these, Mitchell et al. (2022) explored field program adaptations at an oncology field placement, Morris et al. (2020) examined a new program started by social work students to fulfill their field hour requirement, and Perone (2021) used a case study designed to assess attitudes of students regarding online instruction and virtual field placements. One literature review was included (Szcygiel & Emery-Fertitta, 2021), which looked at the field termination process and collective trauma experiences of students, including a student example and faculty reflections. Studies by Crocetto (2021) and Melero et al. (2021), discussed institutional field program responses to the COVID-19 crisis in the form of field notes. The two mixed-method articles included in this review used the same set of participant responses. Davis and Mirick (2021) explored student experiences in the virtual learning environment, COVID-19–related termination processes, and social work during the pandemic. Mirick and Davis (2021) focused on student needs created by the pandemic and the students’ perspectives on program response. Only one of the articles selected was a quantitative study, and it presented the perspectives of both students and field instructors (Jun et al., 2021). Of the remaining two articles reviewed, one reflected on student experiences in modified field placements (Bloomberg et al., 2022), and the other reflected on the actions of field faculty at a school of social work (Dempsey et al., 2022).

As defined by PRISMA- ScR, scoping reviews are a method of evidence mapping when investigating a broad topic, rather than pursuing a narrow, defined question (McGowan et al., 2020; Tricco et al., 2018). Our scoping review objective was to describe how social work field education responded to the challenges presented by COVID-19. In doing so, we identified the available literature’s concepts and characteristics, summarized findings, and discussed knowledge gaps to suggest areas for further research. After reviewing all included articles, information applicable to our objectives was themed and combined to answer our research questions narratively. Our scoping review of the literature resulted in the emergence of five themes: (a) remote field work, (b) alternative activities, (c) communication, (d) technology, and (e) early termination with clients.

Remote Field Work

Remote field work can be defined as field work that is not accomplished in person but rather via technology of some kind, while students remain in their homes. Remote field work can also refer to activities completed by students online (training, meetings, workshops) that may or may not be related to the students’ original field placement activities. The COVID-19 crisis resulted in social work programs rapidly and unexpectedly altering field work requirements and seeking methods to conduct remote field work as a response to state mandates regarding social distancing. As a result, the loss of in-person client contact became a difficult and sobering reality, as instructors produced curriculum reflecting the needed changes (Perone, 2021). Individualized consideration was available in some programs when deciding to remain in or vacate a field placement (Mirick & Davis, 2021). For most students, traditional field placement transitioned to remote field work, with a reduction in required field hours (Crocetto, 2021; Mirick & Davis, 2021; Perone, 2021) or early termination of field services (Melero et al., 2021).

Davis and Mirick (2021) conducted a nationwide survey of BSW (n = 632) and MSW students (n = 80), reporting that 42.5% of students surveyed participated in remote field placements. Of the 330 students who provided information on the delivery of services, 125 reported that services occurred nondirectly, and 205 reported that field services were conducted over the telephone and video conferencing. These authors also reported that 56.6% of students abruptly terminated field work with clients, and notably, of those delivering field services remotely, only 15.9 % received preparatory training on effective engagement in remote field. A remediating measure noted by Perone (2021) was that some schools adopted a pass/fail grading system during this time.

To promote student success and provide supportive measures to field agencies, one large school of social work surveyed 120 field agencies supervising 430 students to understand the agencies’ abilities to provide remote learning experiences. Transition assistance was then provided by the school to support agencies and students with terminating student–client relationships and separating from agency personnel. Additionally, the school assisted students with the completion of agency documentation and the return of agency-owned materials (Melero et al., 2021).

Concurrently, changes occurred in how student evaluations of field services were conducted. Both field evaluation visits and final evaluations of field work were completed remotely by institutions of higher learning (Jun et al., 2021; Melero et al., 2021). When agencies terminated student internships, field liaisons at one large school of social work became field supervisors, implementing remote assignments and activities (Melero et al., 2021). Although that school and the other social work programs discussed in the reviewed literature offered remote supervision, when live field supervision was not available some students were uncomfortable continuing their placement (Dempsey et al., 2022).

Further complicating matters, the ability to remain in the field was hindered by the type of service delivered. Essential agencies, such as shelter/housing programs and meal services, continued to operate in person but for safety reasons could no longer provide placement to students (Melero et al., 2021). A student case example that included reflections by field faculty noted that internships were abruptly terminated with little recourse for students (Szcygiel & Emery-Fertitta, 2021). The students experienced confusion, anger, and grief related to the loss of field time and the minimal contact that continued with field clients via phone or virtually.

Alternate Activities

Alternate activities can be defined as activities, projects, or trainings that occur outside of the actual field location and are conducted electronically. Consequently, supervision of these remote activities usually occurred via teleconferencing. At the start of the pandemic, the alternate activities, altered field schedules, and altered means of service delivery required schools of social work to develop flexible ways to fulfill field hours. In the study by Davis and Mirick (2021), 47% of students surveyed completed alternate field activities conducted at home. These activities included report writing, projects, participation in virtual meetings and trainings, and policy-related work. Allowances were made for extensions to assignment due dates, reduction in the number of required assignments, and variations in how missed assignments were made up. Where applicable, assignment makeup allowed for remote time with clients as well as other school- and home-related responsibilities. Very few instructors continued with originally planned assignments (Mirick & Davis, 2021). One school’s contingency plan mostly included assignments in the form of reflexive papers on specified topics (Dempsey et al., 2022).

Despite these changes, there was indication that some students deemed the field hour requirement as unrealistic in the crisis climate (Mirick & Davis, 2021). One school of social work studied by Melero et al. (2021) responded to student frustration regarding online assignments and activities by making appropriate adjustments to assigned work and exams. They also initiated an alternate activity to supplement field work in which students created a macro-level psychoeducation project on COVID-19 relevant to their assigned field agencies’ client needs, in addition to other alternate actives that were adjusted according to their online field transition (Melero et al., 2021). Furthermore, free remote trainings were provided to field agencies and students to assist with completing learning plans. Perone (2021) self-reflected on challenges as a social work instructor in making necessary adjustments. To accommodate the alterations in field, an individual policy-brief assignment was modified into a group policy-brief project due to the inability of students to use field placement policy to complete the requirement.

As programs scrambled to meet the new demands, one school of social work at a private liberal arts college implemented a virtual learning plan to fulfill field hour requirements. This learning plan included 17 skill labs, free registration to an antiracism summit, biweekly group supervision, two role-play events, 20 online modules, and 20 live virtual events such as panel discussions and job fairs (Crocetto et al., 2021). A different approach was taken by another school in which students engaged in a self-directed learning project. This led to the formation of a community-based online service that satisfied field hour requirements (Morris et al., 2020).

Another variation on meeting field hour requirements was presented by Mitchell et al. (2022), who described how an oncology social work internship implemented “patient-less” field while preserving the clinical learning experience. Alternate learning practices were accomplished by presentations made by hospital staff via phone or video platform, patient scenarios guided by learning modules presented via role-play with supervisors, and observation of open, online client support groups. Process recordings, reflective papers, and documentation practice were used as adjunct learning methods (Mitchell et al., 2022).

Communication

In this context, communication is defined as information exchanged among schools of social work, students, and agency-based field supervisors. The articles reviewed indicated that perceptions of communication varied at the onset of the crisis. The lack of effective interaction between school-employed field instructors, social work field agency supervisors, and students resulted in miscommunication, fear, and confusion. Jun et al. (2021) asserted that field directors needed to communicate the expectations for field hours and have processes in place for supporting students during transitions in placement, listening to student concerns, working with students on creating alternate field learning plans, modeling self-care, and attending to future career goals. Szczygiel and Emery-Fertitta (2021) presented a student voice that described the emotional struggle experienced by students when announcements about terminating field placements were done via email. In these situations, there was no opportunity for students to process or communicate client needs to anyone involved. In the same article, a field liaison reflected on how open communication with the students by faculty, the office of field education, and field supervisors was often a measure of how well students were supported during the pandemic crisis.

In response to student anxiety, field faculty participated in students’ online classes to address concerns. Additionally, they established drop-in sessions for field agency supervisors (Dempsey et al., 2022). Perone (2021) noted that students felt they should have been included in field-related decisions. Moreover, the author advocated for the “promotion of student agency” in that including students in the decision-making process had added value and should have been considered.

To encourage continuity during this time of uncertainty, Jun et al. (2021), suggested that programs improve communication between school field instructors and agency field supervisors, and implement a provision allowing for the agency field supervisor to terminate field placement. These authors also reflected on the need for field instructors to elicit reports of the challenges that agency field supervisors cope with, while encouraging supportive contact between field supervisors and students through school-assisted technology. This communication was not made a priority; therefore, there were instances where agencies were unaware that students terminated field placement on the directive of their school (Mirick & Davis, 2021). In contrast, Melero et al. (2021) reported that continuity of communication was accomplished by school field liaisons working together to deliver continuous and consistent information and guidance to students and field agencies. Further, video meetings initiated by field liaisons offered support and guidance to students and fostered the meeting of personal and educational needs.

Some students expressed frustration and were dismayed that their school was not prepared for a crisis (Perone, 2021), and there was a subsequent lack of training on delivering remote services (Davis & Mirick, 2021) including a lack of field learning experiences in general (Perone, 2021). There were instances in which students quickly experienced blurred lines between home time and field hours when engaging in field work online (Perone, 2021), thus indicating the need for training in developing boundaries between remote work and home life (Jun et al., 2021). Jun et al. (2021) reported that within social services, field work has been delivered virtually in the past, yet some educators have not had significant experience with the delivery of social work content and service in the virtual space. These authors also emphasized the need to focus on inclusion of social work competencies in the remote field environment.

Technology

In this context, technology can be defined as electronically assisted communication through the use of computers, tablets, or telephonic devices to maintain engagement with other people in lieu of in-person work. At the advent of the pandemic, social work schools had not been afforded the time to create a plan for technologically directed field placements. Challenges were plentiful, including concerns about the use of personal cell phones and computer functionality (Perone, 2021). Lack of reliable internet connectivity was also noted as problematic by Jun et al. (2021), especially in relation to group projects. Davis and Mirick (2021) discussed “barriers to remote work” including lack of access to the field agency email system, records, computers, and phone line while servicing agency clients remotely. Similar barriers were noted by Mitchell et al. (2022) and Dempsey et al. (2022), including the need for educators to abide by ethical standards and practical guidelines when considering the logistics of online field work (Jun et al., 2021). Fortunately, some agencies were technologically sound and were able to offer cellular phones and laptops, while also providing HIPAA compliance and effective training on remote service delivery (Melero et al., 2021).

Although technological challenges created impediments, innovations prevented the complete cessation of field education. As indicated by Mitchell et al. (2022), technology fostered indirect practice skills which can produce meaningful client care. Advancements in videoconferencing platforms provided an avenue for educational and supportive measures (Jun et al., 2021; Melero et al., 2021; Mirick & Davis, 2021; Perone, 2021) and for client contact (Davis & Mirick, 2021). These platforms also furnished the opportunity for students to engage with each other and complete group assignments (Perone, 2021). Similarly, prolific use of discussion boards on learning management systems such as Canvas and Blackboard had the advantages of “critical thinking,” efficiency, and increasing student comfort level when expressing opinions (Jun et al., 2021).

Early Termination With Clients

Early termination with clients can be defined as the cessation of services that occurred prior to the planned or expected completion of field services due to the social distancing requirements created by the pandemic. Issues associated with early and unforeseen client termination were negative emotions, lack of strategies for informing clients, and, in a few cases, easy endings (Davis & Mirick, 2021). Contributing to the distress of termination, schools of social work were indecisive and gave mixed messages about when to terminate clients. Due to the nature of some placements, contact with clients was severed and proper client termination was not possible (Davis & Mirick, 2021); however, a small number of study participants indicated that terminations were done properly.

Jun et al. (2021) recognized the service delivery constraints of agency field supervisors, which provided insight into the reasons students felt disconnected from their field placements. A large percentage of field supervisors (86%) indicated that client contact was delivered or concluded remotely. Constraints experienced by field supervisors included feeling stressed by having reduced staff, limited access to residential facilities, and closed court systems. There was a significant emotional toll for the students, which included their immense concern for clients (Szczygiel & Emery-Fertitta, 2021). These authors noted one student who reflected on feeling fear and worry that her abandonment would retraumatize the school-age clients she served. Their article also relayed the emotional toll on a field supervisor as a result of supporting students through the termination phase and navigating the resultant grief. Similarly, students expressed guilt, sadness, and concern that their clients may experience a trauma response when abrupt terminations were required (Bloomberg et al., 2022).

Discussion

This scoping review assessed literature to determine how baccalaureate- and master’s-level social work programs navigated adjustments to the signature pedagogy of social work education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eleven articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Five recurrent themes emerged from the articles included in the scoping review: (a) remote field work, (b) alternate activities, (c) communication, (d) technology, and (e) early termination. These themes highlighted pandemic-initiated field placement modifications experienced by social work students and faculty. Challenging new obstacles included adapting to virtual classrooms and remote field placements, attempting to meet the required number of field hours, having the resources available to engage in field placement activities, and meeting the needs of clients in the field agencies.

Similarly, the pandemic affected other disciplines regarding the need to adjust pedagogical approaches. Aspects of our findings parallel that of nursing education. A study examining COVID-19–related clinical rotation disruptions revealed abrupt shifts in how education and clinical field experiences were conducted, thus leading to communication dilemmas, missed opportunities, and emotional responses to the loss of in-person contact (Diaz et al., 2021).

In this review, the scoped literature reflected the dedication, determination, and resiliency of social work programs across the United States, which not only survived during the pandemic, but strived to support students and their communities. The challenges encountered by schools of social work during COVID-19 are similar to barriers resulting from previous natural and man-made disasters. Nguyen (2020) highlighted the impacts of Hurricane Florence on the School of Social Work at The University of North Carolina Wilmington. Students lost significant instructional time when field modifications were required. Some faculty used class time as an opportunity to assess students and provide academic and emotional support. Department faculty obtained approval from the CSWE for students to apply recovery-related volunteer efforts toward required field hours.

Social work students in New York City faced similar challenges immediately following the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2001. Some agencies were forced to close temporarily, and others had difficulty accessing the technology and resources necessary to provide services. In some cases, agencies were unable to offer their usual services due to the disaster and subsequent reduced clientele. Matthieu et al. (2007) indicated that this sometimes resulted in “the pacing or slowing down of many requirements” (p. 33).

Modified social work field placements appear to be common during disasters.As a result of mandated restrictions during COVID-19, the schools included in the articles reviewed in this study rapidly developed alternative activities, including case studies, simulations, online trainings, and other assignments, to provide a means for students to complete the required field hours and gain social work skills (Mitchell et al., 2022). When the modifications were initiated, some students struggled to find a healthy balance between work and home life. In some cases, these complications were further compounded by the experience of the collective trauma of the pandemic. This was especially poignant for students who had to assist their children with schooling or caring for other family members while they engaged in virtual field activities. However, when considering that engaging in uncompensated field work has historically led to financial and familial stressors (Smith et al., 2021), the advent of remote field work may alleviate some of this burden by reducing or eliminating childcare and transportation costs. Future research is needed to explore this and other possible advantages of remote field work.

Even when not faced with pandemic-related challenges, social workers and other “helping” professionals are at risk of burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary trauma throughout their careers (Grise-Owens & Miller, 2021; Kanno & Giddings, 2017). Lemieux et al. (2020) conducted a study assessing the mental health of social work students, including those completing field placement, following the Great Flood of 2016 in the state of Louisiana. The researchers observed that nearly 60% of students participating in the study displayed symptoms of clinical depression. While the students engaged in a variety of healthy coping strategies to manage their stress, unhealthy coping strategies also occurred: 16.9% reported alcohol and other substance use (Lemieux et al., 2020). Literature suggests that schools of social work and social work educators have a duty to teach students to recognize the need for self-compassion and self-care in a profession where practitioners often put the needs of others before themselves (Grise-Owens & Miller, 2021; Matthieu et al., 2007).

As revealed in this review, the lessons gleaned from COVID-19 serve as an opportunity for schools of social work and field programs to plan for future disasters and to understand the resulting implications, particularly for field education. The pandemic experience fundamentally altered the way field education was carried out, and highlighted the fact that schools of social work need to be intentional in planning for disasters such as COVID-19. As such, implications for field practice include developing contingency plans for future disasters, including natural and man-made disasters and pandemics. These plans need to offer a variety of alternative field activities that promote critical thinking while modeling probable scenarios. Future studies can appraise the success of the alternative activities. Creative approaches that identify and publicize the technological resources available to students and faculty, and strategies that foster communication and collaboration between field faculty and students and between field supervisors and schools of social work during times of uncertainty need to be considered. During the COVID-19 pandemic, students who received regular updates and routine communication from their social work programs tended to have a more positive experience, and felt their concerns were validated and included in the decision-making process (Mirick & Davis. 2021).

Considering the shared trauma experienced by many during the pandemic, research highlights the obligation to respond to the needs of the student community using a trauma-informed approach to instruction (Barros-Lane et al., 2021). We suggest that schools of social work create field committees dedicated to developing a remote field curriculum to contribute to disaster preparedness. To proactively prepare students, field faculty, and field supervisors for contingencies, we further suggest schools build a student disaster resilience module into their curriculum to educate students on disaster-related field policies. This module could explain the application of online technology, contain learning activities and assignments in the event of disaster-related in-person field termination, and provide information on self-care and stress management. Because computers and phones with data plans may not be a financial reality for all students, schools could establish a computer loan service and provide internet connectivity for students in need. Responsive communication between field programs and field supervisors is imperative during disasters, and field programs need to establish contingency plans with field agencies prior to the start of field placements. A hotline for field-related questions could be established for both field agencies and students.

Technological advancements have expanded learning opportunities for students far beyond what was available before COVID-19. Given this reality, schools of social work need to consider the value of technology as a complement to in-person field placements. Remote simulation exercises could provide exposure to clinical and other field placements that may otherwise not be possible (Bogo, 2015). Such remote opportunities could resolve accessibility challenges and enhance the overall curriculum.

Implications for research include the need for continued evaluation of modified field programs. Future studies can assess academic institution preparedness for natural and man-made disasters, while identifying the greatest challenges for students according to age, race, ethnicity, and income levels. Additional studies could observe how modified field placements and extenuating circumstances impact social work curriculum development and daily operations among schools of social work. There is also a need for an appraisal of the quantity and quality of remote field hours required to result in an optimal field education experience. Finally, workshops and conferences on field education’s triumphs and tragedies during the COVID-19 pandemic can provide a forum to promote collaboration among schools of social work.

It is important to note that this study had some limitations. Due to the nature of the topic reviewed, the time frame for published articles included in the review was limited. Only 11 articles fully met the inclusion criteria, of which two had the same authors and appeared to use some of the same data. None of the quantitative studies were experimental.

Conclusion

Although limited, this review makes an important contribution to the literature on field education during COVID, and highlights areas of further research. Field education is often referred to as the heart of social work education. It provides students with the opportunity to realize and practice the knowledge obtained in the classroom and develop the skills necessary to become competent micro- and macro-level practitioners. Schools of social work often are required to make adjustments to the content, delivery, and requirements of field education during disasters. This scoping review explored the impacts of COVID-19 on social work field education students in the United States.

References

Ayala, J., Drolet, J., Fulton, A., Hewson, J., Letkemann, L., Baynton, M., Elliott, G., Judge-Stasiak, A., Blaug, C., Gérard Tétreault, A., & Schweizer, E. (2018). Field education in crisis: Experiences of field education coordinators in Canada. Social Work Education, 37(3), 281–293.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1397109

Azman, A., Singh, P., & Isahaque, A. (2021). Implications for social work teaching and learning in Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A reflection. Research and Practice, 20(1-2), 553–560.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325020973308

Barros-Lane, L., Smith, D. S., McCarty, D., Perez, S., & Sirrianni, L. (2021). Assessing a trauma-informed approach to the COVID-19 pandemic in higher education: A mixed methods study. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), S66–S81.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1939825

Bloomberg, S., Tosone, C., Agordo, V. M., Armato, E., Belanga, C., Casanovas, B., Cosenza, A., Downer, B., Eisen, R., Giardina, A., Gupta, S., Horst, T., Kris, J. G., Leon, S., Li, B., Montalbano, M., Moye, S., Pifer, J., Piliere, J., … Zinman, D. (2022). Student reflections on shared trauma: One year later. Clinical Social Work Journal 50, 67–75.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00819-7

Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices and contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 317–324.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

Council on Social Work Education. (2015). 2015 educational policy and accreditation standards.

https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/standards/2015-epas/2015epasandglossary/

Council on Social Work Education. (2022). 2022 educational policy and accreditation standards.

https://www.cswe.org/getmedia/94471c42-13b8-493b-9041-b30f48533d64/2022-EPAS.pdf

Council on Social Work Education. (2022). COVID-19 and social work education.

https://www.cswe.org/about-cswe/covid-19-and-social-work-education/

Crisp, B. R., Stanford, S., & Moulding, N. (2021). Educating social workers in the midst of COVID-19: The value of a principles-led approach to designing educational experiences during the pandemic. British Journal of Social Work, 51(5), 1839–1857.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab108

Crocetto, J. (2021). When field isn’t field anymore: Innovating the undergraduate social work field experience in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. International Social Work 64(5), 742–744.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00208728211031950

Davis, A., & Mirick, R. G. (2021). COVID-19 and social work field education: A descriptive study of students’ experiences. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), 120–136.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1929621

Dempsey, A., Lanzieri, N., Luce, V., de Leon, C., Malhotra, J., & Heckman, A. (2022). Faculty respond to COVID-19: Reflections-on-action in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(1), 11–21.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10615-021-00787-y

Diaz, K., Staffileno, B., & Hamilton, R. (2021). Nursing student experiences in turmoil: A year of the pandemic and social strife during final clinical rotations. Journal of Professional Nursing, 37(5), 978–984.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.07.019

Domakin, A. (2015). The importance of practice learning in social work: Do we practice what we preach? Social Work Education, 34(4), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1026251

Grise-Owens, E., & Miller, J. J. (2021). The role and responsibility of social work education in promoting practitioner self-care. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(4), 636–648.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1951414

Gushwa, M., & Harriman, K. (2019). Paddling against the tide: Contemporary challenges in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(1), 17–22.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0668-3

Hemy, M., Boddy, J., Chee, P., & Sauvage, D. (2016). Social work students “juggling” field placement. Social Work Education, 35(2), 215–228.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1125878

Hill, N., Cleak, H., Egan, R., Ervin, L., & Laughton, J. (2019). Factors that impact a social worker’s capacity to supervise a student. Australian Social Work, 72(2),152–165.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1539111

Jun, J. S., Kremer, K. P., Marseline, D., Lockett, L., & Kurtz, D. L. (2021). Effective social work online education in response to COVID-19. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 41(5), 520–534.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2021.1978614

Kanno, H., & Giddings, M. M. (2017). Hidden trauma victims: Understanding and preventing traumatic stress in mental health professionals. Social Work in Mental Health, 15(3), 331–353.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/15332985.2016.1220442

Lemieux, C. M., Moles, A., Brown, K. M., & Borskey, E. J. (2020). Social work students in the aftermath of the Great Flood of 2016: Mental health, substance use, and adaptive coping. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(4), 630–648.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1661914

Matthieu, M., Ivanoff, A., Lewis, S., & Conroy, K. (2007) Social work field instructors in New York City after 9/11/01. The Clinical Supervisor, 25(1-2), 23–42.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v25n01_03

McGowan, J., Straus, S., Moher, D., Langlois, E. V., O’Brien, K. K., Horsley, T., Aldcroft, A., Zarin, W., Garitty, C. M., Hempel, S., Lillie, E., Tunçalp, Ӧ., & Tricco, A. C. (2020). Reporting scoping reviews—PRISMA SCR extension. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 123, 177–179.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.016

Melero, H., Hernandez, M. Y., & Bagdasaryan, S. (2021). Field note—Social work field education in quarantine: Administrative lessons from the field during a worldwide pandemic, Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), 162–167.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1929623

Mervosh, S., Lu, D., & Swales, V. (2020, April 20). See which states and cities have told residents to stay at home. New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-stay-at-home-order.html

Mirick, R. G., & Davis, A. (2021). Supporting social work students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 41(5), 484–504.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2021.1978612

Mitchell, B., Sarfati, D., & Stewart, M. (2022). COVID-19 and beyond: A prototype for remote/virtual social work field placement. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(1), 3–10.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00788-x

Morris, Z. A., Dragone, E., Peabody, C., & Carr, K. (2020). Isolation in the midst of a pandemic: Social work students rapidly respond to community and field work needs. Social Work Education, 39(8), 1127–1136.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1809649

Nguyen, P. V. (2020). Social work education and Hurricane Florence. Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping, 26(1), 61–67.

https://reflectionsnarrativesofprofessionalhelping.org/index.php/Reflections/article/view/1723.

Perone, A. K. (2021) Surviving the semester during COVID-19: Evolving concerns, innovations, and recommendations. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), 194–208.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1934210

Smith, D. S., Goins, A. M., & Savani, S. (2021). A look in the mirror: Unveiling human rights issues within social work education. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 6(1), 21–31.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-020-00157-7

Szczygiel, P., & Emery-Fertitta, A. (2021). Field placement termination during COVID 19: Lessons on forced termination, parallel process, and shared trauma. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), 137–148.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1932649

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Alderoft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-Scr): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7). 467–473.

https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850