Abstract

The field practicum is social work’s signature pedagogy, but no empirical research has established how many hours students need to develop professional competence. Extensive hours pose hardships for working students, so research should determine minimum and optimal numbers of practicum hours. This quasi-experimental study evaluated changes to field hours for BSW, Foundation MSW, and Advanced MSW students. Reduced hours did not harm BSW and Advanced MSW students’ preparedness. However, increased hours may have aided Foundation MSW students’ skill development. Social work programs should consider students’ professional development and their school, work, and family obligations when setting field practicum hours requirements.

Keywords: field practicum; field hours; practice readiness; social work internship; evaluation

Introduction

The field practicum is the signature pedagogy of social work (Council on Social Work Education [CSWE], 2015a). Its intent is “to integrate the theoretical and conceptual contribution of the classroom with the practical world of the practice setting” (CSWE, 2015a, p. 12). In order to bridge theory and practice, signature pedagogies involve the head (knowledge and cognitions), the heart (emotions, ethics, and use of self), and the hand (learning by doing) (Shulman, 2005). In their practicum placements, social work students work with client systems under the supervision of a seasoned social worker, ideally experiencing diverse client systems and taking part in many aspects of social work practice while at their practicum agency (Kay & Curington, 2018). The field practicum is vital to effective social work education.

Social work offers both undergraduate and graduate degrees for those who wish to practice social work. Undergraduate students earn a Bachelors of Social Work (BSW) degree that prepares them to be generalist social workers. Masters of Social Work (MSW) degrees include a Foundation year of generalist social work training and an Advanced year of specialization training. Fully accredited programs may offer advanced standing admission to students who have earned a BSW degree, which only requires completion of the Advanced year of specialization training. Specialization training prepares students to work with “a specific population, problem area, method of intervention, perspective, or approach to practice” (CSWE, 2015a, p. 12).

At the generalist level, students must master nine competencies specified by CSWE (2015a) (e.g., Competency 2: Engage Diversity and Difference in Practice). These competencies are operationalized into behaviors describing how knowledge, values, skills, and cognitive and affective processes are employed in mastery of the competency (e.g., apply and communicate understanding of the importance of diversity and difference in shaping life experiences in practice at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels). At the specialist level, social work programs may either extend and enhance the same competencies to apply to the specialization, and/or add additional competencies specific to the specialization. For example, a social work program that retains Competency 2 for its specialist level might operationalize it with higher-level behaviors (e.g., use knowledge of the effects of oppression, discrimination, structural social inequality, and historical trauma on clients to guide intervention planning). Social work practicum placements afford opportunities for both BSW and MSW students to master the competencies. CSWE requires students to complete a minimum of 400 practicum hours for a BSW and 900 hours for a MSW (2015a), though programs are free to require additional hours. For MSW students who have already earned a BSW, programs may count 400 hours completed as a BSW student towards the 900 hours required for a MSW. CSWE first set minimum requirements for practicum hours in 1982. Raskin, Wayne, and Bogo (2008) suggested that CSWE chose 400 and 900 hours arbitrarily, under political pressure from social work programs, or perhaps (Buck & Sowbel, 2016) for expediency, e.g., two days/week x four semesters ≈ 900 hours. The practicum hours requirements haven’t changed since then, though there are indications that social work practice, the cost of college, and students’ experiences and responsibilities may all be quite different than they were 38 years ago. Each of these may affect field education.

First, social work practice has changed in recent decades, with clients needing substantial assistance to deal with complex multidimensional problems (Bogo, 2015; Gushwa & Harriman, 2019). Moreover, agency budgets are tight and social workers are busier than ever, with many having to meet productivity requirements. As a result, social workers may not have the time or the freedom to supervise social work students, potentially reducing the number of practicum placements available. At the same time, growth in the number of social work programs across the nation and the increase in the number of social work students (CSWE, 2019) results in more competition among programs to place their students in practicum sites. Most of these practicum placements occur during weekday business hours (CSWE, 2015b), leaving little flexibility for many students who must work to finance their education.

The cost of secondary education has risen much faster than family income (College Board, 2017), with tuition being as much as three times higher than it was 30 years ago, after adjusting for inflation. While financial aid has also increased, nonetheless there is a substantial and widening gap between available grants and the cost of attending college, including tuition, fees, books, and living expenses (College Board, 2019a, 2019b). This is also true for social work students: a survey of 2018 social work graduates found that while 30% of MSW students received school-based scholarships, 38% did not receive grant or scholarship assistance from any source; they reported financing their education through loans and/or work (George Washington University Health Workforce Institute, 2019). This is typical, with most social work students carrying substantial student loans: over $28,000 on average for BSWs and over $45,000 on average for MSWs (CSWE, 2019). To control their amount of student loan debt load, most students work; it is not uncommon for social work students to work 20-30 hours/week in addition to taking classes and completing a practicum (Neill, 2015; Yoon, 2012). In addition, many students also have family or caregiving responsibilities (Buck, Bradley, Robb, & Kirzner, 2012; Raskin et al., 2008).

Students often struggle to balance these obligations, reporting that juggling school, internship, work, and family leaves them stressed, tired, anxious, and burned out, and may compromise their ability to perform both in the classroom (Benner & Curl, 2018) and at their practicum (Johnstone, Brough, Crane, Marston, & Correa-Velez, 2016). Though students often cut down on work hours during their practica, this places an extra financial burden on them and does not relieve the role conflict between practicum and other obligations (Grant-Smith, Gillett-Swan, & Chapman, 2017). Role conflict can be especially difficult for nontraditional (older) students, who may have been working and supporting their families prior to enrolling in school. Nontraditional social work students are relatively common, with a recent survey of social work graduates finding that 46% of BSW students and 56% of MSW students had worked three or more years of work experience before starting their social work education (George Washington University Health Workforce Institute, 2019).

Students who are employed at social service agencies may find it advantageous to keep working if they can reduce or flex their work hours and/or complete their practicum placement at the agency (CSWE, 2015b; Newman, Dannenfelser, Clemmons, & Webster, 2007). Large social service or government agencies may offer some financial assistance for employees to pursue a social work degree, but very few students are able to access such assistance (George Washington University Health Workforce Institute, 2019). In addition to these advantages, work experience is a strength in that working students may bring already-developed skills to the classroom and their practica. However, ongoing work responsibilities may also constrain the time students can spend in school and at their practicum.

As a result, it can be challenging for students to complete their practicum placement hours. In one study of U.S. and Canadian social work students (Buck & Sowbel, 2016), half were unable to consistently finish each week’s practicum hours. While some planned to catch up by spending extra hours or days at their practicum, 25% did not think they could complete the required practicum hours by the end of the term. While student participants in other studies have suggested that flexible or non-traditional practicum hours such as evenings and weekends would be one solution to this problem (Johnstone et al., 2016), very few practicum placements are available outside of regular business hours (CSWE, 2015b). Moreover, paid practicum placements are very rare due to tight agency budgets, so students cannot realistically expect that income from their practicum will replace reduced work income. Thus, students are obliged to add weekday practicum hours to already-full schedules of schoolwork, jobs, family responsibilities, and so forth.

While social workers can and should advocate for policies to relieve the burden of the high cost of education on students, policy change takes time. Another solution might be to change the required number of practicum hours to the minimum number needed to master social work competencies. However, this solution is problematic in that, to date, there have been no empirical studies to establish either the minimum necessary or the optimal number of practicum hours required for mastery of the competencies (Raskin et al., 2008). As such, the current standards of 400 and 900 hours are not empirically based (Coffey & Fisher, 2016). That is, to the authors’ knowledge, there were no studies of field hours prior to CSWE setting requirements in 1982, nor have field hours been empirically tested since then (Coffey & Fisher, 2016). Thus, it is not known how many hours are required for social work students to master the competencies, and whether current requirements reflect the minimal or the optimal number of hours in the field.

The field of social work is not alone in requiring practicum hours prior to graduation. For instance, nursing is similar in that it offers both undergraduate and graduate degrees, with licensure available at both levels. At the masters level, 500 clinical (practicum) hours are required; Bowling, Cooper, Kellish, Kubin, and Smith (2018) noted that this standard was based on studies investigating the link between clinical hours and competence. However, Bowling et al. (2018) stated that similar studies about competency development in undergraduate nursing students do not exist; perhaps consequently, there are no national requirements for undergraduate nursing students’ clinical hours. Bowling et al. (2018) urged the nursing field to build evidence about the number of hours required for competency at each level.

There have also been calls for social work to build evidence about its signature pedagogy. The 2014 Field Education Summit (CSWE, 2014) identified priorities for advancing field education. One of these called for the development of evidence-based practice on field education, including conducting research to determine necessary elements for high quality field education. Research to determine whether 400 and 900 practicum hours are necessary and/or sufficient for mastery of social work competencies would be consistent with this priority.

The current study was conducted to begin to build evidence about practicum hours. Utilizing field practicum outcome data for BSW and MSW students and surveys completed by field supervisors, it investigates whether changing the required number of field hours for BSW and MSW students results in differential preparedness to practice social work.

Methods

Setting and Design

This study was conducted at a regional campus of a Midwest public university, with well-established accredited BSW and MSW programs. Most classes are on site, though some are available online. The majority of social work students work part- or full-time while attending school. To better accommodate working MSW students, in the year before the study began the social work program moved all MSW classes to evenings and weekends.

The MSW program admits students with a BSW into the one-year advanced standing MSW program, and those with another undergraduate degree into the two-year regular MSW program (Foundation year, then Advanced year). All three levels of field placements (senior year BSW [BSW], Foundation MSW, and Advanced MSW) involve two semesters with the same organization. At each level, the field placements run concurrently with classes in fall and spring semesters, and must be completed by the end of spring semester. Throughout the study, the social work program required more hours than CSWE’s minimum of 400 for BSW and 900 for MSW.

Between the 2016-17 (Year 1) and 2017-18 (Year 2) school years, changes were made to field hour requirements at all three levels. In Year 2, BSW students spent one less 16-hour week at their field practica each semester due to the University reducing the semester length by one week. Advanced MSW students’ practica were reduced from 22.5 to 17.5 hours/week (approximately 75 fewer hours/semester). This change was a component of the program’s initiative to better accommodate working students. Foundation MSW students’ practica increased from 16 to 17.5 hours/week (approximately 20 additional hours/semester), in order to align the practicum requirements for the two years of MSW education. These changes in field hours provided an opportunity for a naturalistic experiment of the effects of changes in field hours on student preparedness for social work. At each level (BSW, Foundation MSW, and Advanced MSW), the authors compared field outcomes for students who were at that level in Year 1 to outcomes for students who were at that same level in Year 2.

Though this was a quasi-experimental study (no random assignment to level of schooling or to Year 1 versus Year 2), the only major difference between the two years was the change in field hours. First, there were no other changes made to the curriculum at any level. Second, the student body was made up of students with similar characteristics in both years: ~85% female, reflective of the racial/ethnic makeup of the region (20-30% African-American, 4-6% Latino, 65-70% Caucasian), and ~50% first-generation college students. No Year 1 student repeated the same level internship in Year 2 (e.g., none failed in Year 1), so at each level the Year 1 cohort was comprised of completely different students than the Year 2 cohort. Thus, at each level the Year 1 and Year 2 cohorts were comparable and engaged in equivalent educational experiences except for the change in field hours. It should be noted that some of the Year 2 Advanced MSW students had been BSW or Foundation MSW students during Year 1. However, it was not possible to track students over time since the field outcome data were de-identified. The study was deemed exempt by the University’s institutional review board.

Participants

Participants were all of the senior year BSW, Foundation MSW, and Advanced MSW students who completed both fall and spring semester practicum placements in either year. They participated through use of administrative outcome data for their field practicum placements. Note that students did not personally provide additional information for the study, as the study focused on comparing, at each level, the differential effectiveness of changing field hour requirements on student preparedness for social work. Since students did not experience both requirements at any level, they would not have been able to compare the requirements’ effectiveness. In addition to the student participants, experienced field supervisors for Year 2 students also participated in the study. (“Experienced” means they had supervised the social work program’s students in at least one previous year.)

Measures

Two measures were used for this study. First, the authors used de-identified administrative data consisting of student outcomes of fall and spring semester field practica for both years. These data were from the evaluation component of each student’s Field Practicum Learning Contract. This measure included scores for each competency (CSWE, 2015a) and for the corresponding behaviors. Field instructors scored students at the end of each semester on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all skilled, 3 = adequate skill for that level of student, 5 = exceptional skill for that level of student), with the goal that most students would achieve better than merely adequate skill (4 or 5) by the end of the practicum placement. While this measure is specific to the social work program, this type of outcome measurement system (scoring students on each competency and behavior using a five-point scale) is fairly common among social work programs (cf. Jensen, Brigham, & Rosenfeld, 2019; Rowe, Kim, Chung, & Hessenauer, 2020).

The second measure was an anonymous online survey created by the authors and completed by Year 2 field supervisors in the fall semester after Year 2. It had a screening question (for field supervisor experience), a description of changes made to field hours at each level, space for written comments about the changes in field hours, and three questions about each Year 2 student’s end-of-school-year readiness, each rated on a 0-10 scale:

1. How well prepared was the student to start their social work career (or to move on to their Advanced MSW year, in the case of Foundation MSW students)? 0 = not at all prepared, 5 = adequately prepared, 10 = very well prepared.

2. Compared to previous supervisees from the social work program, how well prepared was the student to start their social work career (or move on to the Advanced MSW year)? 0 = much worse than previous students, 5 = similar to previous students, 10 = much better than previous students.

3. How much did the change in field hours affect the student’s readiness for social work? 0 = very negative impact, 5 = no impact, 10 = very positive impact.

Procedure

The de-identified administrative field practicum outcome data already existed prior to the study. In the fall semester after Year 2, researchers sent emails to all Year 2 field supervisors, explaining the study and requesting that they click the embedded anonymous link to participate in the survey. The link led to a consent form; participants indicated consent by advancing to the next page to start the survey. Inexperienced field supervisors (in their first year supervising the social work program’s students) were screened out before providing student ratings. Participants could skip any question that they did not want to answer. Researchers sent two reminder emails to supervisors at two-week intervals to encourage those who had not participated to do so.

Analysis

Researchers used IBM SPSS (version 25) to analyze administrative (field outcome) data. Analyses were conducted on scores for each competency. To determine whether fall-to-spring changes in competency scores were different for Year 1 and Year 2 students, repeated-measures 2-way ANOVAs were conducted for each competency. A separate series of ANOVAs was conducted at each level (BSW, Foundation MSW, and Advanced MSW).

To determine if median field supervisor ratings of Year 2 students were significantly different from 5 (a neutral value for each question), researchers conducted single-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. This test was selected because of low n in the Foundation MSW and Advanced MSW groups. Researchers used the Real-Statistics Excel add-in (Zaiontz, 2019) for these analyses. Again, these tests were conducted separately for each level of students. Field supervisor qualitative comments were grouped by student level, then read to identify common themes expressed by many supervisors, as well as themes specific to one level of practicum placement.

Results

There were 46 BSW students who completed both fall and spring semester practicum placements in Year 1, and 48 in Year 2; 14 Foundation MSW students who completed both fall and spring semester practicum placements in each year; and 32 Advanced MSW students in who completed both fall and spring semester practicum placements in Year 1 and 34 in Year 2. Administrative field outcome data were available for 100% of BSW, Foundation MSW, and Advanced MSW students in both Year 1 and Year 2.

However, not all field supervisors provided ratings of Year 2 students via the online survey: there were 19 responses for BSW students (39.6% response rate), 4 responses for Foundation MSW students (28.6% response rate), and 11 responses for Advanced MSW students (35.3% response rate). (These numbers do not include several inexperienced field supervisors who consented but were ineligible to participate.) These response rates are comparable to those achieved in other studies in which field supervisors provided data: Gelman (2011) reported a 27.0% response rate from eligible field supervisors and Kay and Curington (2018) reported a 27.9% response rate from eligible field supervisors.

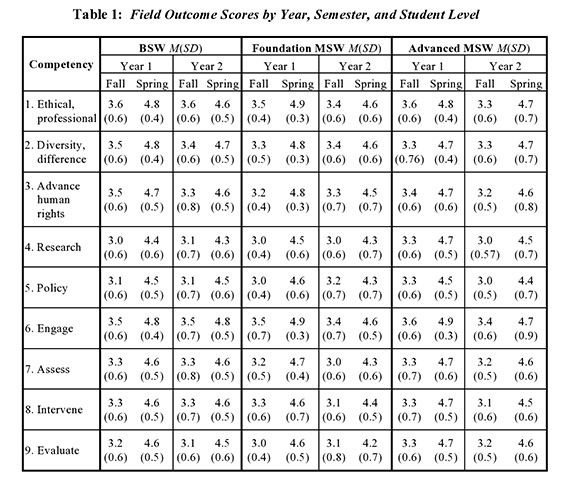

Average field outcome scores were lower for fall (3.0-3.6) than for spring semesters (4.2-4.9, see Table 1), which is expected. The lowest outcome scores were usually for Competency 4 (Engage in Practice-Informed Research and Research-Informed Practice) and Competency 5 (Engage in Policy Practice), with Foundation MSW students also typically earning lower scores for Competency 9 (Evaluate Practice With Individuals, Families, Groups, Organizations, and Communities). Scores were highest for Competency 1 (Demonstrate Ethical and Professional Behavior) and Competency 6 (Engage With Individuals, Families, Groups, Organizations, and Communities).

Results of the two-way ANOVAs were consistent for the nine competencies across all three levels of students: there was not a significant interaction between semester and year, p = .15-.99, or a significant main effect for year, p = .11-.99. That is, Year 1 students’ ratings were equivalent to Year 2 students’ ratings. This was true for all nine competencies for BSW, Foundation MSW, and Advanced MSW students. However, there was a significant main effect for semester, all p < .001. All three levels of students improved from the end of the fall semester to the end of the spring semester, for all competencies. The one exception to this pattern of results was a significant interaction on Competency 5 (policy) for Foundation MSW students, p = .04. Year 2 students scored higher than Year 1 students in fall, but lower than Year 1 students in spring (see Table 1). However, as there were 27 ANOVAs, this significant interaction is likely due to family-wise alpha error rather than being a legitimate effect (McDonald, 2014).

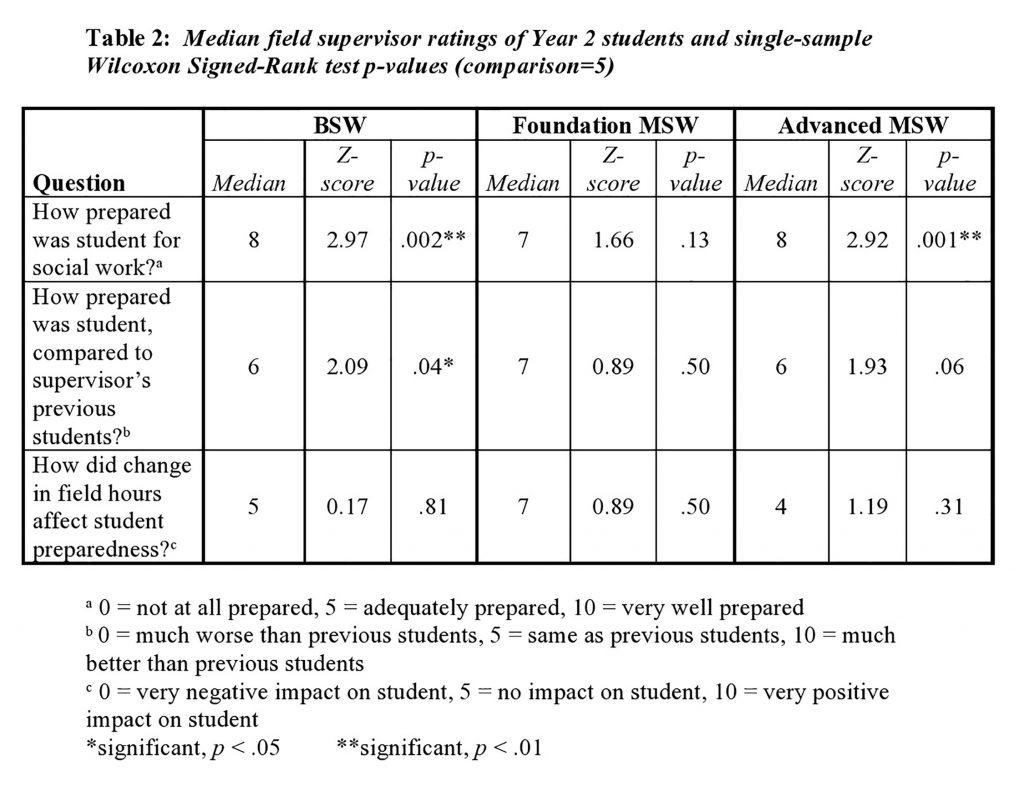

Median supervisor ratings of student preparedness to begin social work careers (or go on to their Advanced MSW year, for Foundation MSW students) were 7 or 8, see Table 2. Single-sample Wilcoxon Signed-rank tests revealed that Foundation MSW students were adequately prepared (non-significant test, which means that the median score was not significantly different from the reference score of 5 [adequately prepared]). However, BSW students and Advanced MSW students were significantly better than adequately prepared (significant test). Comparisons of Year 2 students with supervisors’ previous students were generally favorable (median = 6-7), with BSW students being significantly better prepared than supervisors’ previous students (significant test) but Foundation MSW and Advanced MSW students being equally prepared as previous students (non-significant test). Supervisors reported that the change in field hours had no impact on BSW and Advanced MSW students (median = 4-5, non-significant test). Ratings of the impact of additional hours on Foundation MSW students was higher (median = 7), though this was not significantly different than 5 (no impact).

Many supervisors expanded on this finding (no impact of changing practicum hours) in the comments section. They explained that they felt readiness was more a function of personal factors – capabilities, efforts, and experience – than the specific number of hours spent at the practicum. For instance, one supervisor stated, “I think different students need more attention, or less attention, than other students. [It’s] not necessarily dependent on the number of hours they get in the field, more of an age, maturity, etc. thing.” Another supervisor had a similar assessment, stating that it would be ideal to be able to customize practicum placements based on a student’s abilities and human service experience.

In keeping with this theme, most supervisors of BSW students did not feel that having one less week of field practicum per semester made any difference to BSW students: “I do not feel that the fewer number of hours impacted the intern’s preparedness to enter the work world.” Another supervisor explained that, “the changes were so minimal (only one less week) for the BSW senior level student that I supervised, that there was no impact to their work or readiness to enter the field after graduation.” Although minimal, having one less week per semester did necessitate changing established procedures for some placements. For instance, a supervisor noted that the change required some adjustment to the student’s projects and goals for the field practicum, but they did not feel that this impacted the student’s readiness for social work.

Only one BSW supervisor disapproved of the reduction in hours. They stated, “students do not spend enough time in field hours, so it is hard to understand why you would lower the requirement […] more learning is done on the job than in a classroom.” In a similar vein, the only Foundation MSW supervisor to write a comment felt that the increase in Foundation MSW hours did not go far enough. They advised increasing practica to 24 hours/week, indicating that it would be ideal because it would be “much more like being employed at your placement.”

Supervisors of Advanced MSW students noted some disadvantages of requiring ~75 fewer hours per semester. Several stated that students were simply not at the practicum enough hours to get the full experience of day-to-day social work practice at the agency. For instance, students were not always able to participate in all aspects of client care. One supervisor noted, “the change in hours made it difficult for the [Year 2] students to see multiple aspects of treatment, including seeing a patient through a full case.” That is, Year 1 students’ additional practicum hours “allowed them time to see a patient one last time before discharge, which they did not have last year [in Year 2].” Another disadvantage of the reduction in hours was that it created a tension between time spent on routine duties and time spent on larger projects. One supervisor noted, “the interns learn less about the day-to-day due to making time for bigger projects.” Conversely, another supervisor noted that the reduction in hours limited students’ participation in long-term projects. “The change did impact the number of macro projects the students were involved in. I do think it made some of the mezzo interventions difficult to complete.”

In summary, the primary disadvantage of a large reduction in practicum hours for Advanced MSW students was that they had less of an opportunity to experience the full range of social work tasks and client situations at the agency. It is notable that supervisors did not report that the reduction in hours hurt Advanced MSW students’ preparedness to practice as MSW social workers, simply that students’ reduced availability allowed them to have fewer experiences while they were at their practicum. Indeed, one supervisor of an Advanced MSW student reported that requiring fewer hours could be advantageous to students’ overall well-being. This supervisor felt that it “allowed [students] more time to focus on the curriculum needs of classes, to pass without major stressors.”

Discussion

This study is the first to empirically evaluate the effectiveness of different field practicum hour requirements in preparing students to practice social work. The authors used multiple data sources to determine whether making a small reduction, large reduction, or small increase to the required number of practicum hours resulted in differential preparedness in two cohorts of students at three levels of social work education: BSW, Foundation MSW, and Advanced MSW.

The social work program’s students face similar challenges as those described by Buck et al. (2012): they juggle multiple obligations, including work, school, and often family. While the changes to BSW and Foundation MSW field hours were made for administrative reasons, the program lowered the requirement for Advanced MSW practicum hours in order to better accommodate working MSW students’ needs. However, this change was contingent on Advanced MSW students achieving satisfactory competence with fewer practicum hours. The authors found that Year 2 Advanced MSW students achieved similar competency to Year 1 students; indeed, they were rated as being better than adequately prepared for social work, although they spent ~75 fewer hours per semester at their practicum placement. Field supervisors’ comments indicated that, although students missed out on some experiences, they were nonetheless ready to begin their social work careers.

The small reduction in hours for BSW students had similar results: better-than-adequate preparation for a career in social work. Field supervisors’ comments overwhelmingly indicated that the small reduction was not noticeable and had no overall impact on students. Thus, it appears that small (~32 hours) or large (~150) reductions in practicum hours over the course of a year for social work students nearing the end of their training may not impair their readiness for professional social work. Additional hours could broaden their experience with client systems, and may be necessary for continuity of care purposes at some practicum placements (Kay & Curington, 2018); but those hours could be “icing on the cake” in that they may further enhance expertise in students who have already mastered required competencies. For instance, additional hours could allow a BSW student who has already become proficient in working with culturally diverse families (Competency 2 & Competency 8) to assist with organizing the community (Competency 8) to advocate for laws (Competency 5) to ban discriminatory hiring practices. This would entail simultaneously utilizing skills from multiple competencies: sharpening macro practice skills (intervening with communities, and policy practice) with clients from diverse populations.

Not all supervisors approved of requiring fewer hours at the practicum; indeed, several urged increases at both the BSW and MSW levels. Kay and Curington (2018) argued that, ideally, practicum placement requirements should balance agency and clients’ needs (for more hours) with students’ needs (for fewer hours, to accommodate their busy lives). Ultimately, the ideal for social work’s signature pedagogy would be for it to require sufficient hours for students to encounter a range of client systems and situations, so that they may develop appropriate social work judgment and good knowledge of procedures. This is in keeping with a statement in CSWE’s (2015a) Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards, “Signature pedagogies are elements of instruction and of socialization that teach future practitioners the fundamental dimensions of professional work in their discipline – to think, to perform, and to act ethically and with integrity” (p. 12). For students who have less preparation in social work prior to the practicum placement (i.e., Foundation MSW students) and/or little prior experience in human services, fewer practicum hours may not be sufficient for them to develop these fundamental dimensions of social work.

In the current study, field supervisor ratings suggested that the additional practicum hours may have enhanced Foundation MSW students’ readiness for social work. (Note: though non-significant, the statistical test was underpowered with n = 4 field supervisors, so its results are not definitive.) The beneficial effect of additional hours may be due to the Foundation MSW students being new to social work – in their first semester – when they begin their practicum. In contrast with BSW students, who complete several years of social work classes prior to their senior year practicum, the social work program’s Foundation MSW students start their formal socialization into the field of social work – both content and structure (Miller, 2010) – simultaneously with their first practicum placement. As students new to social work, Foundation MSW students may begin their placement with very basic skills (Walton, 2005), and are thus often anxious about being able to help client systems at their first practicum (Gelman, 2004). Thus, additional hours at the Foundation MSW practicum may facilitate their professional development in a way that is less necessary for students near the end of their social work education. This may be especially true of those with little human service experience prior to entering the social work program.

One difficulty in studying the number of practicum hours necessary for competency is that the practicum placement is not the only venue in which students learn about and practice each of the required competencies. For instance, students also study theory, interventions, and the competencies in the classroom. Some social work programs also require that students enroll in seminars concurrently with their practicum placements; these are intended to help students integrate classroom learning with practice opportunities encountered at the practicum. To truly determine which educational elements are necessary or sufficient for students to master the competencies, research would also have to investigate these other learning opportunities in addition to the practicum placement.

Implications and Future Research

This study focused on changes to practicum hours above those currently required by CSWE, so its findings may not apply to changes resulting in practicum requirements below current CSWE standards. Indeed, fall semester competency scores consistently indicated that students had only achieved minimal competency expected for their level. The social work program’s goal is to ensure that students are more than minimally competent, which means that half of the currently required hours would be insufficient preparation for social work practice. However, results of this study suggest that fewer practicum placement hours may not harm BSW and Advanced MSW students’ mastery of social work competencies and preparedness for practice.

Future research should replicate this study with other populations of social work students, at social work programs offering varied Advanced MSW specializations, and with other specific numbers of practicum hours at all three levels. It would also be helpful to include students’ perspectives on their preparedness for social work in future studies. An additional step would be to build the evidence base about current CSWE standards. While social work programs are not allowed to set practicum requirements below current CSWE standards, shorter practicum placements could be simulated by measuring student competence and readiness for social work practice at multiple points throughout their practicum placement. In addition, while the current study focused on student mastery of all of the competencies, another approach would be to determine how many hours are required to master each competency. It is possible that mastery would occur at different numbers of practicum hours for each competency; furthermore, studies should determine whether students with extensive work experience in social services prior to starting their social work education are able to achieve mastery of each competency with fewer practicum hours than are needed by traditional students. Finally, future research should feature students’ views of both the stresses and the benefits associated with social work’s signature pedagogy.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had both strengths and limitations. One strength is that the authors were able to assess the effects, of both large and small changes in field hours, across all three levels of social work students. Another strength is that the authors had administrative outcome data for 100% of the students in both years. These data are routinely collected on all students for each competency and behavior, a common practice among social work programs (Jensen et al., 2019; Rowe et al., 2020). The spring scores are high, which might indicate a “halo effect” (Ayasse, 2016), in which evaluations are enhanced by the relationship built between the student and supervisor. Improvements to the current scoring system, such as the addition of clear definitions of behaviors, or rubrics illustrating no/minimal/exceptional mastery of each competency (Ayasse, 2016) could minimize the halo effect. Another strength is that the authors were able to compare two different assessments of Year 2 students’ readiness for social work (administrative outcome data and field supervisor ratings), although the online rating questions were not yet validated as they were created for this study. In addition, less than half of the field supervisors provided ratings for Year 2 students via the online survey. Although findings from field supervisor ratings parallel results from the administrative outcome data for Year 2 students, it is not clear whether students whose field supervisors responded to the online survey were typically prepared, or whether the field supervisors who participated were a biased sample in that their students were less well prepared (or better prepared) for social work than were students whose field supervisors did not respond to email requests to complete the online survey. This is a limitation to the study. Future research could address this limitation by recruiting field supervisors for the study in person, for instance at the student’s final evaluation of the school year.

Another limitation is that students did not directly participate in the study. While students could not have compared the differential effectiveness of different requirements for field hours in Year 1 and Year 2 (because they only experienced one set of requirements), nonetheless they could have provided information on how prepared they felt they were for social work practice. While there is evidence from other studies that students’ judgments of their own preparedness generally parallel field outcome data (cf. Regehr, Bogo, & Regehr, 2011), without direct student participation in the study we cannot know whether students’ judgments would have been similar to the existing two sources of data for this study.

Conclusion

There are many challenges to effective field education. This research study started to build the evidence base about one challenge: the number of field practicum hours necessary to prepare social work students to be professional social workers. The results suggest that requiring many field practicum hours above current CSWE standards may not be necessary to prepare Advanced MSW or senior year BSW social work students for a career in social work. However, additional hours may assist students who are early in their social work education (e.g., Foundation MSW students) to build their social work skills. Students’ professional development should be balanced with their many obligations when setting field practicum requirements. Future research into requirements for field hours should investigate whether different numbers of practicum hours would be necessary to prepare Advanced MSW students for effective practice in different specializations. In addition, research should determine both the minimum necessary and the optimal number of field practicum hours for students to master the competencies and be well-prepared for social work practice.

References

Ayasse, R. H. (2016). Engaging field instructors to develop measurements of student learning outcomes in school social work settings. Field Educator, 6(1). Retrieved from https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/engaging-field-instructors-to-develop-measurements-of-student-learning-outcomes-in-school-social-work-settings

Benner , K., & Curl, A. L. (2018). Exhausted, stressed, and disengaged: Does employment create burnout for social work students? Journal of Social Work Education, 54(2), 300–309. doi:10.1080/10437797.2017.1341858

Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices and contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43, 317–234. doi:10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

Bowling, A. M., Cooper, R., Kellish, A., Kubin, L., & Smith, T. (2018). No evidence to support number of clinical hours necessary for nursing competency. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 39, 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2017.12.012

Buck, P. W., Bradley, J., Robb, L., & Kirzner, R. S. (2012). Complex and competing demands in field education: A qualitative study of field directors’ experiences. Field Educator, 2(2). Retrieved from https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/complex-and-competing-demands-in-field-education

Buck, P. W., & Sowbel, L. (2016). The logistics of practicum: Implications for field education. Field Educator, 6(1). Retrieved from https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/the-logistics-of-practicum-implications-for-field-education

Coffey, D. S., & Fisher, W. T. (2016). The future of field education: A conversation with Darla Spence Coffey. Field Educator, 6(1). Retrieved from https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/the-future-of-field-education-a-conversation-with-darla-spence-coffey

College Board. (2017). Trends in college pricing 2017. Retrieved from https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-college-pricing-2017-full-report.pdf

College Board. (2019a). Trends in college pricing 2019. Retrieved from https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-college-pricing-2019-full-report.pdf

College board. (2019b). Trends in student aid 2019. Retrieved from https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-student-aid-2019-full-report.pdf

Council on Social Work Education. (2014). Report of the CSWE summit on field education 2014. Retrieved from https://www.cswe.org/CSWE/media/AccredidationPDFs/FieldSummitreport-FINALforWeb.pdf

Council on Social Work Education. (2015a). Educational policy and accreditation standards. Retrieved from https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Standards-and-Policies/2015-EPAS/2015EPASandGlossary.pdf.aspx

Council on Social Work Education. (2015b). Findings from the 2015 state of field education survey. Retrieved from https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/08068351-037f-473f-b773-2b90ad5af0b0/Findings-From-the-2015-State-of-Field-Education-Su.aspx

Council on Social Work Education. (2019). 2018 statistics on social work education in the United States. Retrieved from https://cswe.org/getattachment/Research-Statistics/Annual-Program-Study/2018-Statistics-on-Social-Work-Education-in-the-United-States.pdf.aspx

Gelman, C. R. (2004). Anxiety experienced by foundation-year MSW students entering field placement: Implications for admissions, curriculum, and field education. Journal of Social Work Education, 40(1), 39–54. doi:10.1080/10437797.2004.10778478

Gelman, C. R. (2011). Field instructors’ perspectives on foundation year MSW students’ preplacement anxiety. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 31(3), 295–312. doi:10.1080/08841233.2011.580252

George Washington University Health Workforce Institute. (2019). From social work education to social work practice: Results of the survey of 2018 social work graduates. Report submitted to the Council on Social Work Education and National Workforce Initiative Steering Committee. Council on Social Work Education: Alexandria, VA. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=eLsquD1s2qI%3d&portalid=0

Grant-Smith, D., Gillett-Swan, J., & Chapman, R. (2017). WiL wellbeing: Exploring the impacts of unpaid practicum on student wellbeing. Report submitted to the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. Curtin University: Perth, Australia. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/109505/1/GrantSmith_WIL.pdf

Gushwa, M., & Harriman, K. (2019). Paddling against the tide: Contemporary challenges in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47, 17–22. doi:10.1007/s10615-018-0668-3

Jensen, T. M., Brigham, R. B., & Rosenfeld, L. J. (2019). A psychometric analysis of field evaluation instruments designed to measure students’ generalist-level social work competencies. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(3), 537–550. doi:10.1080/10437797.2019.1567416

Johnstone, E., Brough, M., Crane, P., Marston, G., & Correa-Velez, I. (2016). Field placement and the impact of financial stress on social work and human service students. Australian Social Work, 69(4), 481–494. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2016.1181769

Kay, E. S., & Curington, A. M. (2018). Preparing masters’ students for social work practice: The perspective of field instructors. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 37(8), 968–976. doi:10.1080/02615479.2018.1490396

McDonald, J. H. (2014). Handbook of biological statistics (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Sparky House Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.biostathandbook.com

Miller, S. E. (2010). A conceptual framework for the professional socialization of social workers. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 20(7), 924–938. doi:10.1080/10911351003751934

Neill, C. (2015). Rising student employment: The role of tuition fees. Education Economics, 23(1), 101–121. doi:10.1080/09645292.2013.818104

Newman, B. S., Dannenfelser, P. L., Clemmons, V., & Webster, S. (2007). Working to learn: Internships for today’s social work students. Journal of Social Work Education, 43(3), 513–528. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2007.200500566

Raskin, M. S., Wayne, J., & Bogo, M. (2008). Revisiting field education standards. Journal of Social Work Education, 44(2), 173–188. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2008.200600142

Regehr, C., Bogo, M., & Regehr, G. (2011). The development of an online practice-based evaluation tool for social work. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(4), 469–475. doi:10.1177/1049731510395948

Rowe, J. M., Kim, Y., Chung, Y., & Hessenauer, S. (2020). Development and validation of a field evaluation instrument to assess student competency. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(1), 142–154. doi:10.1080/10437797.2018.1548988

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 134(3), 52–59. doi:10.1162/0011526054622015

Walton, C. (2005). How well does the preparation for practice delivered at the university prepare the student for their first practice learning opportunity in the Social Work Degree? Journal of Practice Teaching, 6(3), 62–81. doi:10.1921/jpts.v6i3.332

Yoon, I. (2012). Debt burdens among MSW graduates: A national cross-sectional study. Journal of Social Work Education, 48(1), 105–125. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2012.201000058

Zaiontz, C. (2019). Real statistics using Excel [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://www.real-statistics.com