Abstract

This qualitative study explored the advice of graduating BSW students (N=180) to upper-level students about to embark on their practicum field experience. Using a content analysis methodology, students’ field experience reflections on preparing for the practicum centered on three major themes: practical tips for picking a practicum, being teachable, and finding value in the practicum experience. The desired goal for this inquiry was to provide information that would prove useful to students entering their practicum experience, the field instructors providing on-site supervision, and the BSW field directors conducting orientation to both of these groups.

Keywords: practicum; BSW students; content analysis; field experiences

Introduction

Instructors in undergraduate BSW programs see firsthand the importance of field practicum. Our storied profession has long acknowledged this aspect of professional learning and the pivotal role that field practicum plays in the development of social workers (Abram, Hartung, & Wernet, 2000). The aspect of applied learning and sharing of experiences from field practice students completing their placements holds value from a phenomenological approach.

The challenge for any social work program is developing a dynamic field education program that equips students to bridge from the classroom to the field seamlessly (Boitel & Fromm, 2014; Larkin, 2019). There is value in asking graduating social work students to self-reflect on their time in the field, and ask what they thought were important learning aspects of their practicum. The literature is almost non-existent as it applies to preparing the next generation of bachelor level students for a successful practicum based on the advice of graduating seniors. For this study, graduating students were asked to self-reflect about their recent practicum experience and provide feedback about what they would want other students heading into the practicum to know about this experience. The use of constructivism theory of learning as a lens allowed for the sharing of these insights to serve as a blueprint for future practicum students (Bada, 2015). Providing graduating students finishing their field hours an opportunity to self-reflect about their lived practicum experience sets the stage for this inquiry.

Literature Review

In order to bring relevance to this study, reviewing the current literature surrounding field education, self-reflection, and constructivism theory of learning was necessary. Self-reflection, a vital practice for any social worker, helps ensure the commitment to ethical practice in the profession (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2017). Asking students to self-reflect about their field experiences provides an avenue for them to create meaning of those learning opportunities while using constructivism theory of learning as a framework within the context of field education (Bada, 2015; Urdang, 2010). Separately, each of these three areas have been researched and proven noteworthy for the field of social work. However, there is value and significance when we integrate all three of these areas into a research study.

Field Experience

Field education is widely recognized as a pivotal experience for students to have the opportunity to synthesize their learned knowledge and theory with application to practice under the guidance of a credentialed social work professional (Chen & Russell, 2019; Williamson, Hostetter, Byers, & Huggins, 2010; Young, 2014). The Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), the national accreditation body for education programs, requires field education as the essential standard in preparing social work students in the practice (CSWE, 2015). Some research has been completed regarding specific preparation of students as they encounter many issues common in social work, such as trauma and other emotional distress (Chen & Russell, 2019; Didham, Dromgole, Csiernik, Karley, & Hurley, 2011; Dill, 2017; Farchi, Cohen, & Mosek, 2014; Fulton, 2012). However, little research or investigation is found that is focused on preparing BSW students more holistically, especially related to students’ expectations of and attitudes toward practicum experience. Because of student anxiety and distress regarding practicum, as evidenced by multiple studies regarding graduate student anxiety, researchers and educators are beginning to understand the importance of a more comprehensive approach to the preparation for bachelor’s students entering the social work practicum (Kamali, Clary, & Frye, 2017; Katz, Tufford, Bogo, & Regehr, 2014; Williamson et al., 2010).

Since the purpose of the field experience is to integrate academic learning and practical skills, entering practicum with a teachable attitude, remaining neutral as a learner observer, and possessing a humble spirit allows students to remain open-minded and attain the most beneficial learning from the field experience (Danowski, 2012; Young, 2014). Young (2014) advised practicum students to avoid looking at classmates’ placements with envy if they seem to be going particularly well and reassured students that even a placement with a difficult beginning can transition into an opportunity to learn and practice social work skills. This was echoed by Danowski (2012) who stated, “Even the worst placement, however, can be rich in learning experiences” (p. 13). A review of scholarly articles related to social work student placement reveals research that indicate graduate students suffer a variety of difficulties during their field placement; thus it is possible additional preparation at the BSW-level pre-placement stage might be prudent (Kamali et al., 2017). Guiding students to address unrealistic expectations and attitudes and to deal with any personal emotional concerns before practicum assists students in employing and honing their skills in practicum without troubling distractions (Kamali et al., 2017). Students would be wise to research and choose thoughtfully and carefully the agency with whom they will potentially serve as intern (Baird, 2014).

Self-Reflection

Research has brought to light evidence that it is important for BSW students to be encouraged to explore their emotional preparedness to enter field practicum with an emphasis on the need for self-care, self-reflection, and awareness (Harr & Moore, 2011; Lyter & Smith, 2004; Marlowe, Appleton, Chinnery, & Stratum; 2015; Williamson et al., 2010). There are multiple benefits from a student’s use of self-examination and reflection. This exercise can build greater competence, help in situations of ethical dilemmas, and create a strong professional grounding in which to build upon (Urdang, 2010). Reflecting upon experiences in placement allows students at all levels of practice to process thoughts, feelings, and reactions to field and the struggles beginning social work students encounter (Urdang, 2010). Sharing these insights, from those recently completing their field experience, with future field students may hold better outcomes including increased confidence, less anxiety, and an overall sense of being more prepared by those venturing into the endeavor for the first time (Flanagan & Wilson, 2018; Kamali et al., 2017).

Constructivism Theory of Learning

Constructivism theory of learning uses shared experiences of individuals from a social and cultural context to create and prescribe learning (Bada, 2015). Individuals develop their own reality giving it meaning as they experience life through a lens created by past experiences and the world around them (Pritchard & Woollard, 2010). Students who recently completed their practicum utilize self-reflection about the pre-placement and field placement experiences. Students’ interactions with the social work faculty, field director, field instructor, and agency staff all influence how the students will ascribe meaning to the entire practicum experience.

Current Study

While many CSWE accredited programs solicit feedback from students regarding various aspects of their programs, little research was found on preparing the next generation for a successful practicum using the advice from previous cohorts. The purpose of this study was to explore the advice graduating BSW students completing their final practicum, if given the opportunity, would share with upper-level students. In hindsight, would BSW students do anything differently as they prepared for practicum? It was expected that the advice from these BSW seniors, as they reflect back on their field experiences, would provide valuable insight into those key areas needed for a successful practicum. It is also expected that these findings might aid in decreasing some of the anxiety associated with field placement which is often found present with many of our undergraduate students (Kamali et al., 2017).

Methods

Research Design

This applied research allowed the authors to take the results of this study and make it applicable to the real world with the intent to use the results to assist in the orientation of students and field instructors as they prepare for the practicum (Patton, 2002). Consequently, this exploratory study used qualitative content analysis to inductively draw meaning from the data and describe the phenomenon (practicum) (Krippendorff, 2013; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2017).

Qualitative content analysis methodology was used to examine the experiences of BSW students recently completing their 456-hour field placement. By using the phenomenon, conventional content analysis as a qualitative analytical research technique allowed coding categories to come directly and inductively from the data using the research question as a lens to make sense out of the experiences of BSW students finishing their practicum (Babbie, 2017; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Krippendorff, 2013; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2017).

Data Collection

This study involved a content analysis of one question from the Self-Assessment II. Originally, the Self-Assessment II assignment was designed to elicit students’ responses that would assist the field director in assessing the needs or gaps of practicum students on a yearly basis. However, it was determined a qualitative content analysis of all the cohorts’ responses might provide information rich data. The motivation to use this question was heightened by the fact that seniors would be using their own field experiences, and in hindsight, provide what they felt were nuggets of wisdom to the next cohort of practicum students.

A convenience sample utilizing BSW students (N=180) from a small Midwestern United States BSW program provided responses for this inquiry. Graduating seniors, finishing up their 456-hour practicum between the years 2010 and 2019, were asked to complete the Self-Assessment II assignment, consisting of ten questions. For the purpose of this study, content analysis was conducted utilizing only one of the questions from this assignment: As we prepare for next year’s practicum, what advice would you give the next cohort of students who are heading into the field?

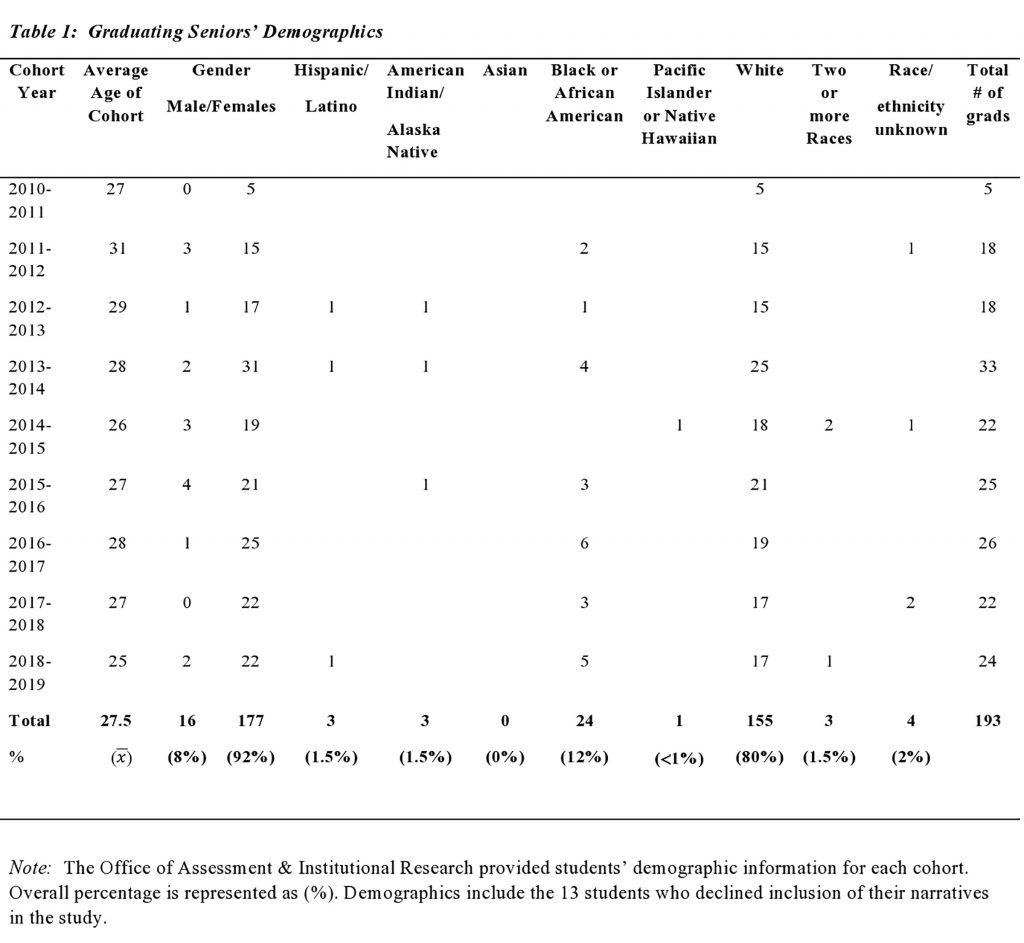

In order to safeguard anonymity, only gender, age, and ethnicity were collected. This information was provided by the University’s Office of Assessment & Institutional Research for all graduating seniors during this time period. Graduating seniors ranged from 22 to 59 years of age with a mean age of 27.5 years. Ninety-two percent were female. Eighty percent self-identified as White and 12% self-identified as Black or African-American. The remaining 8% were either Hispanic/Latino, American Indian/Alaska Native, Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian, two or more races, or had a race/ethnicity that was unknown (see Table 1 in the appendix for full demographic information). All of the students were expected to graduate with a BSW that semester or the following semester, after completing the final practicum.

The University’s IRB was contacted to approve the study. After consulting the University’s IRB Chair, it was determined to be exempt from review based on the low risk, self-reported data and anonymity of the data. However, in order to remain transparent, each cohort was informed of the project and that the narratives would be anonymous, only identifying the year of graduation. Participants were given an opportunity to not have their narratives used in the analysis. Of the 193 graduating seniors between 2010 and 2019, only thirteen students declined inclusion of their narratives in this study, leaving 180 responses that were included in the analysis.

Data Analysis

A conventional qualitative analysis of content approach was used to analyze the data. This allowed for coding categories to come inductively and straight from the data (Krippendorff, 2013; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2017). Data was not transferred to a statistical software for analysis but the analysis was conducted manually by the authors.

Preparing the data for qualitative analysis of content took place after the graduation of each cohort. Seniors’ responses to the Self-Assessment II question was anonymously transferred to a document for analysis. Narratives ranged from one sentence to 17 sentences. The four stages of content analysis discussed by Bengtsson (2016): decontextualisation, recontextualisation, categorization, and compilation were used to examine each sentence. Utilizing the research question as a lens allowed for themes to emerge inductively. Focused coding allowed for the recurrent patterns to be delineated from any subthemes. Subsequently, qualitative analysis of content allowed the authors to move between the data not only within each cohort, but over the time period from 2010 to 2019. Assessing for coding consistency was a necessary process for the authors since coding took place over an extended time period. The authors had to be consistent with the understanding of each coding scheme and determine if these coding schemes had changed or shifted over the time period (Zhang & Wildemuth, 2017).

Reflexivity

In addition to teaching experience, the authors brought to this study varying levels of work experience. Two authors prior to appointment in academia provided several years of field experience to both BSW and MSW practicum students and two of the authors have functioned as a Field Director for a BSW program. In addition, all three authors have gone through the practicum experience at either the BSW or MSW level. As a result, this had the potential to influence how the data was perceived and ultimately could impact the analysis. Elo et al. (2014) stated the importance of self-examination of the researcher on a continual basis is critical so that the interpretations of the data are not being compromised by researcher bias. Consultation and supervision by a social worker not involved with the study were used to mitigate and deal with potential biases of the authors by allowing for alternative viewpoints (Boyd, 2007).

Ensuring Quality Research-Trustworthiness

In order to demonstrate a high-quality study, the purpose, data collection, and analyst triangulation were interrelated in order to bring credibility (validity), dependability (reliability), transferability (generalization), and confirmability (objectivity) to the study (Bengtsson, 2016; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2017). Since the data was collected over a span of ten years resulting in a large sample size, being able to use the results outside the bounds of this study (transferability) was a goal (Bengtsson, 2016; Pearson, Parkin, & Coomber, 2011). The authors were cognizant that since the focus was breadth, in depth data could have been compromised. Coding schemes emerged inductively while using conventional content analysis as a qualitative analytical research technique (Patton, 2002). A conscious effort was made to be aware of personal biases or expectations, and it was essential to not force something to emerge that might not otherwise have become apparent during this process.

The analyst triangulation method was also used as a way for credibility to be strengthened (Bengtsson, 2016; Elo et al., 2014; Patton, 2002). Because the analysis took place in stages, the authors had to keep track of coding decisions and determine if these changed over time (dependability). Analysis took place after each cohort graduation and by using a minimum of two of the authors. Validity in this content analysis was demonstrated via face, social, and content validity (Krippendorff, 2013).It was determined that these sources assisted in determining significance of the study. Prior to this study, the authors began by asking whether this type of study would show significance or benefits to the field of social work. In asking these questions, it helped guide the study to substantive significance.

Results

The authors employed the methodology of qualitative content analysis to identify key themes. Key themes were merged into two major categories: (1) advice for preparing for practicum and (2) advice during the practicum. For the purposes of this article, the authors focused on the three prominent themes found from the reflections of BSW students’ field experiences on preparing for the practicum: finding an agency, be teachable, and knowing it’s all valuable learning opportunities (see Table 2 in the appendix for summary of themes and sub-themes).

Theme 1: Finding an Agency

There were three key actions most students felt upper-level students should do in order to secure a practicum site: (1) do not procrastinate, (2) choose an agency carefully, and (3) go to the interview prepared.

Do not procrastinate. For this BSW program, the process of preparing for practicum begins two semesters prior to the actual practicum, with the actual agency selection taking place the semester prior to the start of the practicum. When preparing to select a potential practicum site, students felt it was helpful to start the process early and not wait until later in the semester to begin looking for a practicum site. Preparation not only included meeting with the field director for direction in identifying potential agencies of interest, but also developing a professional resume and beginning to interview potential practicum sites. For this student, waiting to begin this process put her at a disadvantage: “Get your practicum ‘stuff’ done as soon as possible. Had I done this, I might have been placed in my first or second choice of agencies” (2011-2012 Cohort).

Choose an agency carefully. Many students felt a successful practicum included having an interest in the agency, as seen by this student: “Definitely choose an agency that they [the student] have a great interest in” (2012-2013 Cohort). However, it was felt that picking an agency out of convenience or a desire to help out the agency was not encouraged:

Do not settle for something “simple” or “easy” or for a position because you know the agency needs the help. Find a place that makes you just uneasy enough that you are kept in awe and wonder and a step off balance. That is how you will learn the most. If you are too comfortable, or if it feels “too much like home,” you will not grow nearly as much as you will if you have to rise to a challenge (2012-2013 Cohort).

It also meant not taking an easy route:

Don’t choose the easy path. I could have done my practicum with one of my dear friends and that would have been the easiest and most convenient thing to do. But, if I wanted to pursue my dream of working in a school someday, I needed to do something extraordinary. It was scary, but well worth it (2011-2012 Cohort).

While having an interest in the agency was important, some students felt using the practicum as a way to explore other areas proved advantageous:

Don’t be afraid to pick a practicum that goes outside of [your] interest area. My agency wasn’t anything close to what I had initially wanted for my practicum, but I still learned a lot and was able to gain experience in an area that I most likely wouldn’t have had a chance to do otherwise. Yes, of course it would be nice to spend your practicum hours in a setting that matches up with your interests, but a practicum is one of the few opportunities you get to experience new things, go outside of your comfort zone, and explore your options as a social worker before you have to settle down and get your “big girl” job (2013-2014 Cohort).

Don’t do a practicum at the same agency where you work. A sub-theme that surfaced frequently when considering an agency was not to do a practicum at the same agency where a student worked. This theme was present in every cohort that had students completing a paid practicum as an option. Even though students who completed a paid practicum were required to identify new learning opportunities, and in many cases a new field instructor, their advice was simply to not do this, as seen by this student, “Make sure that you’re NOT doing your practicum at the same place you are currently employed”(2013-2014 Cohort).

Go to the interview prepared. Students had to take the initiative when picking the right agency and this began by going to the interview prepared. This student stated, “Work on good interviewing skills and have a good resume” (2012-2013 Cohort). In addition to good interviewing skills and a professional resume, students felt it was important to have an understanding of the agency, as stated by this student, “Research each placement before you call to set up an interview” (2014-2015 Cohort). Finally, students felt taking responsibility to ask questions about the agency, expectations, and roles of employees during the interview was critical, as seen by this student:

Ask a lot of questions during your initial interview. Make sure the agency understands what your role will be there and find out how much support you will have from the employees there. I recommend bringing the field manual with you and skim through it with the potential instructor. Remember you are interviewing them just as they are interviewing you, making sure the learning styles match. Questions are your friend, so ask a lot (2013-2014 Cohort).

One student felt during the interview process it would be advantageous to ask the field instructor how they handle conflict, ethical dilemmas, self-care, and stressful situations and how social workers are perceived in the agency, especially multidisciplinary agencies:

Make sure to ask your field supervisor about self-care and how this concept is implemented, especially during stressful situations. It is important that the field instructor gives detailed examples of how she copes with her daily stress related to her job. Most importantly, how can she help the intern handle stress especially if things start going south, emotionally? I would also ask about how they incorporate the NASW Code of Ethics into their daily work routine. Have the field instructor give an example of a code of ethics violation and what was the outcome. Finally, ask how a social worker will fit in with the agency, especially if the agency has several other majors (2015-2016 Cohort).

Theme 2: Be Teachable

Having a good attitude, being open to new learning opportunities, managing expectations, and taking the initiative were found by many students to provide utility when preparing for the practicum.

Have a good attitude. Some students reported having a good attitude in general about the practicum would assist them in having a good experience and this mind-set should begin early, as seen by this student, “Aim to enjoy the experience. The practicum shouldn’t and doesn’t have to be just a requirement that you must meet for class but an opportunity to expand your skills and knowledge” (2011-2012 Cohort). Students didn’t “sugar-coat” the experience, acknowledging that the experience might be difficult; however, a positive outlook could bring value, “Be optimistic, there will be days that are hard, and days that won’t end. However, take every single day for what it is worth, because you will miss it when it is gone” (2011-2012 Cohort).

Be open to new learning opportunities. Students in every cohort offered a better practicum experience if the student was willing to be open to new learning opportunities. This student suggested openness and approach had everything to do with the experience, “Be open to receive. Don’t think you know it all because when you have that attitude you hinder yourself from learning more” (2012-2013 Cohort). Openness involved thinking outside one’s comfort zone, as stated by this student:

Keep an open mind and be open to try anything and everything available at the site. If students are open to try different things, their practicum will be very successful and a great experience for them. I really enjoyed my practicum because I was open to try anything and kept an open mind when I was trying new things (2015-2016 Cohort).

Interestingly enough, students felt “being open” also applied to personal growth and feedback. “You need to be open to criticism; your placement will have plenty to tell you about” (2015-2016 Cohort). “Try to be open to learning and to your growth as a person. Remember that this is a learning experience so you will make mistakes; but know that mistakes are your friends” (2010-2011 Cohort). Practicum was seen as a time to not only learn about the field of social work, but to also grow as a person. Most students felt this experience would have the potential to open various job options or additional learning experiences, as seen by this student:

Keep an open mind, even if they feel they already know the population they want to work with. Through this experience there could be doors that open you wouldn’t imagine (2013-2014 Cohort).

Being open to learning was felt to create opportunities for personal and professional growth. However, the student had to be teachable.

Be careful with expectations. For many students, the skills, knowledge, and values of social work learned in the classroom created a disconnect, rather than a bridge, to the professional world. As a result, some students felt having a teachable attitude also involved being mindful of expectations regarding the practicum, agency, and themselves. Being aware when these expectations fell short, and acknowledging mistakes would be made, served a purpose as seen by this student’s response:

My advice is, as hard as it is to do, try not to have expectations because you’re just setting yourself up for failure […] And stay true to the profession, the Code of Ethics and to yourself (2010-2011 Cohort).

In some cases, where students had expectations that were too high, flexibility and advocacy were essential skills needed to have a successful practicum experience:

Just roll with the punches. Your practicum is not going to be all roses and it surely isn’t going to be everything you expected. I would tell them not to set their expectations too high and to remember to advocate for themselves (2012-2013 Cohort).

Take the initiative. Students who could be responsible for their own learning, and not depend on the field instructor, agency, or field director, found the field experience to be more positive. This social work student shared how initiative was critical in order to practice social work skills in the field:

Be prepared to work for what you want. Don’t go into a placement and think it’s all going to fall into your lap. Go and get what you need. And if you still don’t get it ask and/or let it be known what you are missing and needing. This experience is for you to learn and gain knowledge; sometimes you may have to be the teacher (2012-2013 Cohort).

For this student, taking the initiative also meant taking an active part and involving others in the learning:

Study too long, ask too many questions, spend as much time with professors and practicum supervisors as you possibly can, and don’t be afraid to raise the bar every chance you get. Be okay with the idea that it may make classmates feel obligated to raise the bar themselves. Our Social Work Department is not for lollygaggers and bottom feeders ☺ (2010-2011 Cohort).

Finally, initiative concerned itself with putting in the effort to acquire as much learning and experiences as possible. Doing just enough to get the BSW was seen as a missed opportunity for personal and professional growth. This student articulated the importance of capturing as much as possible not only via the college experience but the practicum as well:

Really, really invest yourself in it. I see people approach school fully intending to do the minimum they can and spend as little time and mental bandwidth as they possibly can on it. This is sad. Take full advantage of as many opportunities as possible. You have paid whatever price to utilize the resources that the university has to offer. I guess if you spend time devising ways to elude the mental, spiritual, and physical challenges that college presents individuals the opportunity to participate in [you] must enjoy mediocrity. A degree may make you a candidate for a job, but if you don’t have interviewing skills, you probably won’t get it (2010-2011 Cohort).

While mediocrity may have been the path traveled by some during the practicum, doing “just enough to get by” had future consequences:

Make the most of your experience and work hard. I would say that it is mostly the student’s responsibility to ensure that their practicum is a worthwhile and good experience. I would also advise that they take it seriously, because it will be for many of them, the first impression they make on the social work community, and it should be a good one (2013-2014 Cohort).

Theme 3: It’s All Valuable Learning Opportunities

Some students reported there was purpose for everything experienced prior to and during the practicum and that acknowledging this could prove useful to other students preparing for practicum. Advice centered on finding value in the day-to-day activities as well as the benefits of the practicum for future utility.

Find value in the practicum. Students did not have to like their practicum in order to learn or discover value in it. One student stated, “I think that keeping their eyes open and trying to find the learning experience in everything that they do during their practicum will give them the best experience possible” (2012-2013 Cohort). However, students repeatedly reported that learning took place, regardless of how they felt about it. This advice meant negative feelings towards a practicum did not equate that the practicum was not useful or helpful for their social work career. Valuable learning could take place, even if the student did not enjoy the site:

No matter how they [students] feel about the practicum, it can be a learning experience. Really, your time at your practicum is what you make of it, so make the most out of it. You need to understand how important the relationships you form at your practicum can be [for] your coworkers or even boss one day (2014-2015 Cohort).

How or what a student thought or felt about the practicum did not have to set the path for the student’s future, as seen by this student, “Your practicum does not define what you have to do the rest of your life. You can work with whatever population your little heart desires” (2018-2019 Cohort).

This experience will help you one day. Most students related there was function in all aspects of the practicum, “Everything you are learning is important and you will use in your career” (2015-2016 Cohort), so it was important to utilize the practicum experiences. Students were painstakingly aware that other professionals were watching them which could prove beneficial or not, as depicted by this student:

This is not something to be afraid of, nothing but good can come from this whole experience if you look at it that way. Even though you aren’t being paid for your time, you are gaining experience and networking. Just like [professor] always says, “You never know who you are going to run into.” The impression you make on somebody has the ability to either work in your favor or hurt you in future endeavors (2013-2014 Cohort).

Be prepared. A surprise finding for the researchers was, when looking back at the field experience, students stated they felt prepared to handle practicum but wished they had been more serious about retaining or remembering the classroom information as articulated by this student:

Read as much as you can before going into the field. I found myself wishing that I had engaged more heavily in the reading assignments prior to entering the field. While I did feel well prepared for practicum, I do see that there was room for improvement (2013-2014).

Yet one student felt learning was more than just having the head knowledge from the classroom setting. The applied learning brought about something that could not be taught in the classroom but had to be experienced firsthand. Learning in the field held a much higher stake than in the classroom:

It is all well and good to work hard in your classes and dedicate yourself to the academics but the instructors are completely serious when they are tough on you for things applicable to the real world. No matter how well prepared you think you are for the practicum it is not enough because it must be experienced and felt with the heart. Instructors cannot teach that. High marks are good and desirable but the world does not give A’s and B’s nor is this a term paper you can write and then wonder what you wrote about. You are being groomed to take charge and make the best decisions possible for people in real difficulties and with real emotions. They [clients] will look to you. This type of feeling and weight of responsibility can only be passed to an individual through practicum (2012-2013 Cohort).

Participants provided insight into what was most useful and would benefit the upcoming cohort. The advice to fellow classmates, such as securing a practicum site, being teachable, and using each experience as a learning opportunity, was meant to be intentional when preparing for practicum.

Discussion

The desired goal for this inquiry was to provide information that would prove useful to students entering their practicum field experience, the field instructors providing on-site supervision of these students, and the BSW field directors conducting orientation to both of these groups. The graduating seniors’ feedback could prove useful in equipping other students as they prepare for the upcoming field experience by hearing the shared lived experiences and what they might change if given the opportunity. In addition, the data underscores the importance of students taking responsibility for their learning with the field instructors acting as a guide and role model for effective and ethical practice (Young, 2014). This insight could lead field directors in better assigning agencies and students to each other as well as enhancing the orientation process for both students and field instructors. The findings not only aligned with current research on preparing students for practicum when it came to reducing anxiety, being open minded, and creating positive relationships with field instructors (Chen & Russell, 2019; Danowski, 2012; Young, 2014), but also advances the research field as data comes directly from BSW students’ perspectives in preparing for practicum.

University social work programs focus on preparing BSW students for their field practicum from a skills perspective achieved through academic instruction including theory, evidence-based research, ethics, and rehearsal of skills in the classroom environment. A lack of confidence in handling the field role as a burgeoning social work professional, though somewhat normal for most students, increases stress for the undergraduate social work student upon entering their Bachelor-level field practicum (Katz et al., 2014). The realities of the day-to-day role may overwhelm a practicum student’s desire to apply their learned skills. Lee and Fortune (2013) found higher satisfaction with the practicum and an increase of professional skillset when students were able to take advantage of various applied learning opportunities. Lyter and Smith (2004) found there can be a discrepancy between the curriculum and the practical expectations in the field, which would in fact underscore the need to evaluate how social work students are prepared to enter their practicum experience.

Providing students opportunities to “practice” skills learned in the classroom should be the signature pedagogy of any applied learning program and constitutes a vital part of any curriculum (CSWE, 2015). BSW field education programs have a front row seat to the professional learning and see the crucial role that field practicum plays in the development of competent professionals (Abram et al., 2000). The ongoing challenge for programs is designing curriculum that prepares its students to enter the field with the necessary values, skills, and knowledge. Often, these practices are dictated by the guidelines of each program and are often influenced by the accreditation or certification process, but rarely are the experiences of those who have completed the field experience sought.

The results of this study have been used to augment and strengthen the authors’ field program. Enhancements were made to include the findings to the field orientation seminar for students and field instructors. Faculty have been able to incorporate the findings into discussions with students surrounding upcoming practicums. The student-led social work organization held a mixer for their peers, allowing the seniors to talk about their experiences in practicum, thereby creating an opportunity for mentoring to begin (Inoue et al., 2017). The biggest use of the research findings has been with the creation of a new course to bridge the student from the classroom to the field (Kamali et al., 2017).

As graduating seniors share their advice with fellow students, the goal would be students about to begin the process of obtaining a practicum would learn from the experiences of their peers and modify their own behaviors as they prepare for this learning experience. Learning transfer takes place by using an applied learning experience and the learner’s prior knowledge (Boitel & Fromm, 2014). As students prepare to engage in the practicum, they can utilize the concepts of constructivism theory of learning in order to develop their own reality giving it meaning, with the understanding these insights can lead to a more successful learning experience (Pritchard & Woollard, 2010).

Limitations

Like many research studies, this study had limitations. One limitation was the geographical makeup of the sample. Since this was a convenience sample, participants were from one university and primarily lived in the Midwest area. Possible future research could include other BSW programs from various locations. Additionally, social response bias was seen as a limitation. Since the students’ narratives were for an assignment, the potential to minimize or sugarcoat their experiences was possible. Finally, the potential for researcher bias connected to the inductive nature of this study was also a limitation. While the authors put in place practices to safeguard against researcher bias, the authors recognized the risk was still present.

Implications for Social Work Education

As stated, the lived experiences of students are a valuable asset that can help inform future field practice settings. In addition, creating a venue where graduating seniors can share their experiences directly with fellow students provides learning opportunities and for mentoring relationships to take place. Inoue et al. (2017) found benefits to both the student mentors and to the mentees.

Using these experiences, curriculum and trainings can be developed in order to address gaps found in the curriculum and provide additional skills found vital to the field. Mackie and Anderson (2011) found students demonstrated more competence when their curriculum was embedded with competency-based content. Dill (2017) indicated social work educators should lead in, and field supervisors should demonstrate, the exploration and reflection on student emotional status and preparation for possible distressing field experiences.

Conclusion

The Council of Social Work Education charges its accredited programs to prepare students for competent and effective practice and encourages programs to continually evaluate both the implicit and explicit curriculum (CSWE, 2015). While curriculums are designed with these goals, past students’ experiences should not be ignored. Asking students about their experiences and obtaining their synthesized advice proves only to assist future students and field directors for a more successful practicum experience.

References

Abram, F. Y., Hartung, M. R., & Wernet, S. P. (2000). The nonMSW task supervisor, MSW field instructor, and the practicum student: A triad for high quality field instruction. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 20(1/2), 171–185. doi:10.1300/J067v20n01_11

Babbie, E. R. (2017). The basics of social research (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage.

Bada, S. O. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 5(6), 66-70. doi:10.9790/7388-05616670

Baird, B. N. (2014). The internship, practicum, and field placement handbook: A guide for the helping professions (7th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

Boitel, C. R., & Fromm, L. R. (2014). Defining signature pedagogy in social work education: Learning theory and the learning contract. Journal of Social Work Education, 50(4), 608–622. doi:10.1080/10437797.2014.947161

Boyd, E. (2007). Commentary – Containing the container. Journal of Social Work Practice: Psychotherapeutic Approaches in Health, Welfare and the Community, 21(2), 203–206. doi:10.1080/02650530701371929

Chen, Q., & Russell, R. M. (2019). Students’ reflections on their field practicum: An analysis of BSW student narratives. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 39(1), 60–74. doi:10.1080/08841233.2018.1543224

Council on Social Work Education. (2015). Educational policy and accreditation standards. Retrieved from https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Accreditation-Process/2015-EPAS/2015EPAS_Web_FINAL.pdf.aspx

Danowski, W. A. (2012). In the field: A guide for the social work practicum (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Didham, S., Dromgole, L., Csiernik, R., Karley, M. L., & Hurley, D. (2011). Trauma exposure and the social work practicum. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 31(5), 523–537. doi:10.1080/08841233.2011.615261

Dill, K. (2017). Emotional triggers to field experiences: Preparing students and field instructors. Field Educator, 7(2). Retrieved from https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/emotional-triggers-to-field-experiences-preparing-students-and-field-instructors/

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1). doi:10.1177/2158244014522633

Farchi, M., Cohen, A., & Mosek, A. (2014). Developing specific self-efficacy and resilience as first responders among students of social work and stress and trauma studies. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 34(2), 129–146. doi:10.1080/08841233.2014.894602

Flanagan, N., & Wilson, E. (2018). What makes a good placement? Findings of a social work student-to-student research study. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 37(5), 565–580. doi:10.1080/02615479.2018.1450373

Fulton, A. E. (2012). Dealing with client death and dying: A letter to social work practicum students. Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping, 18(2), 69–76. Retrieved from https://reflectionsnarrativesofprofessionalhelping.org/index.php/Reflections/article/view/51/85

Harr, C., & Moore, B. (2011). Compassion fatigue among social work students in field placements. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 31(3), 350–363. doi:10.1080/08841233.2011.580262

Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

Inoue, M., Tsai, L. C., Lee, J. S., Ihara, E. S., Tompkins, C. J., Aguimatang, J., Fountain, K., & Hudson, S. (2017). Teaching note—Creating an integrative research learning environment for BSW and MSW students. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(4), 759–764. doi:10.1080/10437797.2017.1287027

Kamali, A., Clary, P., & Frye, J. (2017). Preparing BSW students for practicum: Reducing anxiety through bridge to practicum course. Field Educator, 7(1). Retrieved from https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/preparing-bsw-students-for-practicum-reducing-anxiety-through-bridge-to-practicum-course/

Katz, E., Tufford, L., Bogo, M., & Regehr, C. (2014). Illuminating students’ pre-practicum conceptual and emotional states: Implications for field education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 34(1), 96–108. doi:10.1080/08841233.2013.868391

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Larkin, S. (2019). A field guide for social workers: Applying your generalist training. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Lee, M., & Fortune, A. E. (2013). Patterns of field learning activities and their relation to learning outcome. Journal of Social Work Education, 49(3), 420–438. doi:10.1080/10437797.2013.796786

Lyter, S. C., & Smith, S. H. (2004). Connecting the dots from curriculum to practicum. The Clinical Supervisor, 23(2), 31–45. doi:10.1300/j001v23n02_03

Mackie, P. F. E., & Anderson, W. (2011). Reinventing baccalaureate social work program assessment and curriculum mapping under the 2008 EPAS: A conceptual and quantitative model. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 16(1), 1–16. doi:10.5555/basw.16.1.16616271822n4m63

Marlowe, J. M., Appleton, C., Chinnery, S. A., & Stratum, S. V. (2015). The integration of personal and professional selves: Developing students’ critical awareness in social work practice. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 34(1), 60–73. doi:10.1080/02615479.2014.949230

National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Code of ethics. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Pearson, M., Parkin, S., & Coomber, R. (2011). Generalizing applied qualitative research on harm reduction: The example of a public injecting typology. Contemporary Drug Problems, 38(1), 61–91. doi:10.1177/009145091103800104

Pritchard, A., & Woollard, J. (2010). Psychology for the classroom: Constructivism and social learning. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Urdang, E. (2010). Awareness of self—a critical tool. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 29(5), 523–538. doi:10.1080/02615470903164950

Williamson, S., Hostetter, C., Byers, K., & Huggins, P. (2010). I found myself at this practicum: Student reflections on field education. Advances in Social Work, 11(2), 235–247. doi:10.18060/346

Young, S. L. (2014). 8 tips for new social work interns. The New Social Worker. Retrieved from https://www.socialworker.com/feature-articles/field-placement/8-tips-for-new-social-work-interns/

Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. M. (2017). Qualitative analysis of content. In B. M. Wildemuth (Ed.), Application of social research methods to questions in information library science (2nd ed., pp. 318–329). Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Limited.

Appendix

Table 2: Students’ Advice on Preparing for the Practicum

| Themes | Subthemes |

| Finding an agency | Do not procrastinate. |

| Choose an agency carefully. | |

| Don’t do a practicum at the same agency where you work. | |

| Go to the interview prepared. | |

| Be teachable | Have a good attitude. |

| Be open to new learning opportunities. | |

| Be careful with expectations. | |

| Take the initiative. | |

| It’s all valuable learning opportunities | Find value in the practicum. |

| This experience will help you one day. | |

| Be prepared. |