Abstract

This article shares the results of a study designed to identify the most significant challenges in social work field education from the perspectives of Canadian field educators and students. A web-based survey was conducted with 155 participants, and the findings were analyzed thematically. The most significant challenges included lack of preparation, support, and training; the burden of multiple responsibilities and roles; communication and supervision challenges; administrative challenges; COVID-19–related changes to online learning and practice; equity, inclusion, diversity, and access (EIDA); and competition and unfair placement selection procedures. The findings provide insight to inform change in social work field education.

Keywords: field education; practicum; social work; most significant challenges; Canada

In recent years, there has been increasing concern regarding the state of social work field education in Canada (Walsh et al., 2022). Field education is defined as a “component of social work education where students learn to practice social work through delivering social work services in agency and community settings” (Bogo, 2006, p. 163). In our study, the term field education—also referred to as field learning, field instruction, fieldwork, and field practicum in some contexts—is used to describe social work students’ learning experiences in a supervised environment. Field education is widely recognized as the signature pedagogy of social work education because of its proven capacity to prepare students to enter the professional field through apprenticeship, experiential learning, and guided reflection (Ayala et al., 2017; Bogo, 2015; Wayne et al., 2010).

In Canada, most social work students complete two field education placements during their Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) program and one placement during their Master of Social Work (MSW) program. Field education placements vary in length, but typically range from 400 to 700 hours. These placements are completed in diverse settings, including community-based, research-based, and clinically-based organizations. Field education placements are supervised by a field instructor who is a qualified social work professional, and students receive ongoing feedback and evaluation throughout their placements. Field instructors are responsible for ensuring that students are provided with appropriate learning opportunities and experiences, and for guiding and supporting students in their professional development.

Previous research on the context of field education illustrates a national crisis due to agency funding cuts, a decreased commitment to education at the agency level, and an increased number of social work programs (Bogo et al., 2020). Due to a high number of complex caseloads, many practicing social workers are unwilling or incapable of accepting practicum students. Consequently, there is a lack of supply despite continued high student demand for practicum opportunities (Bogo et al., 2020).

In response to the longstanding, multilayered challenges in field education experienced by Canadian social work students, field education coordinators/directors, and field educators, the Field Education Committee (FEC) of the Canadian Association for Social Work Education (CASWE) formally acknowledged how these challenges have amounted to an undeniable crisis in social work field education (Ayala et al., 2017). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has added a new dimension and complexity within the field education landscape and social work practice (Archer-Kuhn et al., 2020; Ashcroft et al., 2021; Drolet et al., 2020). The pandemic has had far-reaching effects, with evolving challenges and uncertainties. Social workers have undergone transformative changes in practice, such as the rapid uptake of virtual technologies due to social distancing requirements (Ashcroft et al., 2021). Social work practitioners have experienced negative consequences, including increased workload, loss of employment, redeployment to new settings, forced early retirement, greater concerns for personal health and safety, and struggles with field education opportunities that limit graduates’ employment potential (Ashcroft et al., 2021).

The literature demonstrates that both challenges and benefits have been associated with the transition to virtual care, adapting services, and working with clients with increasing complexities (Ashcroft et al., 2021; Banks et al., 2020). In the case of field education, COVID-19 prompted a dramatic shift to virtual learning environments, including virtual social services delivery and implementation. Consequently, there is a need to better understand the current challenges in field education from diverse perspectives and to develop sustainable models of social work field education. This article explores the most significant challenges in field education from the perspectives of BSW and MSW students and field educators, including field education coordinators and directors and faculty liaisons, in CASWE-accredited social work programs. This study contributes to the ongoing dialogue to inform the development of sustainable models of social work field education in Canada (Drolet & Harriman, 2020).

Challenges in Field Education

Previous literature on social work field education documents several challenges regarding placements, resources, and staffing. Social work field education programs rely heavily on social service agencies and organizations to provide practical learning opportunities for students (Bogo & Globerman, 1995). Due to staff shortages, agency pressures, demanding workloads, time constraints, and insufficient resources, there are significant rising challenges with recruiting high-quality practicum placements for social work students in agencies with field educators (Wayne et al., 2006). Moreover, many universities have policies and procedures for field education that may present or contribute to conflicts among university priorities, those of the practicum settings, and those of the students (Wayne et al., 2006). For example, students reported differences in required hours between the Alberta College of Social Workers (ACSW)/university and the agency, as well as ignorance of religious and cultural accommodations. It is difficult to argue against such policies.

Similarly, university hiring practices can create challenges in field education for faculty liaisons, faculty members, and field educators. For example, faculty hired in social work programs in limited-term positions or in part-time contracts with multiple roles and responsibilities have limited power or longevity in their positions to implement feedback into field education curricula (Wayne et al., 2006). Additionally, implementing social work research curriculum in field education is a recognized challenge (Cameron & Este, 2008; Cox & Burdick, 2001), as is the lack of training for generalist practice and limited opportunities to combine theory with practice at the macro level (Carey & McCardle, 2011). These challenges adversely affect students’ learning outcomes, and holistic and radical reform approaches are required to address rising challenges and barriers in field education (Wayne et al., 2006).

Supervision and Training

Social work students’ ability to integrate theoretical and conceptual classroom learning into practice in their field education experience is of critical importance. Bogo et al. (2017) stated that despite education, practice, and knowledge in social work field education, several prominent challenges to teaching and guiding students about social work skills in practice have been arising for field educators due to structural issues in the agency and in civil society. There are many barriers to field education supervision, including the lack of empirical research on supervision models. Furthermore, research indicates that the quality of training in communication skills in field education raises some concern, as few students feel well prepared to apply these skills in their field settings (Fox & Higgins, 2018). Because of these increasing challenges and barriers, Bogo et al. (2017) stressed the need to re-model supervision and training for social work field education to fulfill educational requirements.

Discrimination

Racism and discrimination have also been identified in the literature as challenges in field education (Razack, 2002). Bernard (2013) stated that “unless there is an acknowledgement of the role of white privilege, white practitioners will fail to understand the subtle dynamics of racism” (p. 1673). This is true not only for racism, but for all forms of discrimination. A survey conducted in Canada by Bhuyan et al. (2017) determined that while the social work profession and program may endorse social justice values, graduates reported limited opportunities to learn about antioppressive practices and the application of social justice theories in their field education. Furthermore, a study in Canada suggested that social work students from Black, Indigenous, Person of Color (BIPOC) communities report experiencing subtle and overt racism such as abuse and derision as everyday features of their field placements (Srikanthan, 2019).

Financial Compensation

The lack of financial compensation for the field practicum has long been a topic for discussion in social work field education in Canada. Hemy et al. (2016) found that students who reported experiencing financial hardship, including having to work additional jobs while completing their studies, “experience more significant levels of psychological distress and stress than those who do not have to work” (p. 220). Furthermore, Collins et al. (2010) reported that students commonly experience fatigue and emotional exhaustion because of feeling overwhelmed. For students dealing with competing responsibilities, dedicating time towards meaningful learning may be an unaffordable luxury. Ryan et al. (2011) found that a lack of financial compensation meant that students often juggled many responsibilities, including paid employment, which undermine their focus on education. Students may be satisfied with simply achieving a passing grade rather than aspiring for academic excellence, thereby adopting “a strategic or shallow approach to learning” (Hemy et al., 2016, p. 222). Similarly, if students are fortunate enough to pick their practicums, they often modify their preferences and make decisions based on practicality rather than educational richness. (Collins et al., 2010; Ryan et al., 2011).

Research indicates that students feel enormous amounts of stress and anxiety when engaged in field education (Allen & Trawver, 2012; Hemy et al., 2016). Students often worry about their ability to balance their personal and academic obligations, as well as their perceived competence while dealing with clients. Students engage in a sort of “balancing/juggling” act when it comes to the multiple roles they manage, including caring for family or simultaneously holding employment while studying and completing field education (Hemy et al., 2016). The importance of having flexible and accessible practicums, as identified by Ryan et al. (2011), means offering students the option of work-based (learning from paid employment) or part-time practicums to help alleviate the challenge of managing multiple responsibilities. Another benefit that flexible placements for students provide is an increased opportunity for social workers who double as field supervisors to balance their caseload alongside field education work, especially with the postpandemic labor shortages affecting nonprofits and social work agencies.

Methodology

This exploratory study used an online survey distributed via Survey Monkey to answer the following research question: What are the most significant challenges in field education in social work? An online survey was chosen for its capability to gather large amounts of data effectively across a large geographic region in a short period of time. A convenience sampling technique was used to engage a population of field educators and students (undergraduate and graduate social work students). The survey was distributed in eight provinces across Canada. In total, 155 respondents participated in the survey from seven provinces across Canada, including Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec, but there was considerable variation in the response rates for each question. Participants completed an online survey in English or in French from March 24 to May 5, 2021. An invitation to participate in the study was delivered by recruitment emails and posts on social media (e.g., Facebook and Twitter). A link to the survey was distributed through CASWE-ACFTS–accredited institutions across Canada, published on the Transforming the Field Education Landscape (TFEL) website, and in TFEL newsletters. All responses were anonymous.

The survey consisted of three open-ended and 14 closed-ended questions, and took approximately 10 minutes to complete. Data collected included respondent demographics, and survey questions were organized into five sections: introductory question (one open-ended question), learning outcomes (four closed-ended questions), accessibility and training (two closed-ended questions), challenges and barriers (one open-ended and two closed-ended questions), supervision and support (four closed-ended questions), compensation (two closed-ended questions), and conclusion (one open-ended question). The survey questions were created first in English and translated into French. Both versions were reviewed by the TFEL research team for context to ensure that the survey was consistent and understandable in both languages. Prior to implementation, the survey was pilot tested on four students and field educators who fell within our target population, to ensure that the questions were relevant and appropriate for respondents.

For data analysis, individual responses were first considered separately to ensure all responses were given equal emphasis. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed on both the close-ended and the open-ended responses and were analyzed thematically to identify themes and patterns across responses. The open-ended questions invited qualitative responses on the most significant field challenge experienced. An initial codebook was created based on the first grouping of completed surveys, which included 41 responses. To ensure intercoder reliability, open-ended questions were individually coded. Five researchers individually coded the responses to the first open-ended question (“Tell us about the most significant challenge you experience in social work field education.”), as researchers agreed that this question most clearly and extensively related to the study’s objectives. Two researchers coded the second open-ended question (“Have you personally experienced discrimination in field education based on your own identities? Please elaborate.”), and three researchers coded the third open-ended question (“Are there any other field challenges you have experienced that were not covered in the sections before? If so, please specify.”)

After creating codes from the initial batch of responses, analyses were discussed and then collated into a master codebook, which was used to code the remaining surveys. Any responses that were different from the codes initially developed were analyzed separately and added to the master codebook afterwards. The themes were named, defined, and refined, then related back to the study objectives in developing the manuscript. Ethical approval for this study was received from the Conjoint Faculties Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (REB 19-0901).

The participants were provided with the opportunity to receive a copy of their responses by email in order to ensure transparency. All participants were required to provide informed consent at the beginning of the survey, and had the option to withdraw from the survey at any time. French responses were translated into English using Google Translate and then examined by a bilingual team member to ensure translational accuracy. From the survey results, two data files—one for English and one for French responses—were created, then merged into a single Excel file for analysis.

Results

Demographic Data

The survey collected 155 responses from respondents in seven provinces. Most participants identified as Caucasian (80%) and female (85%). The majority of respondents were from Newfoundland and Labrador (39%), Alberta (26%), and Ontario (19%). Most participants were field educators (39%), followed by MSW students (34%) and BSW students (26%). Table 1 provides data on participants’ roles in field education, years of experience in field education, geographic location, gender identities, sexual orientation, racial/ethnic identities, and disability status.

Table 1

Demographic Information of the Survey Participants (n =80)a

| % of respondentsb | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Role in FE | ||

| BSW student | 26.25% | 21 |

| MSW student | 33.75% | 27 |

| Field instructor | 38.75% | 31 |

| External field supervisor | 12.5% | 10 |

| Field coordinator/ director | 6.25% | 5 |

| Faculty field liaison | 3.75% | 3 |

| Other | 3.75% | 3 |

| Years of FE experience | ||

| < 1 year | 34.18% | 27 |

| 1–2 years | 25.32% | 20 |

| 3–5 years | 8.86% | 7 |

| 5+ years | 31.65% | 25 |

| Geographic location | ||

| Alberta | 26.25% | 21 |

| British Columbia | 3.75% | 3 |

| Manitoba | 2.5% | 2 |

| New Brunswick | 0% | 0 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 38.75% | 31 |

| Nova Scotia | 3.75% | 3 |

| Ontario | 18.75% | 15 |

| Quebec | 6.25% | 5 |

| Gender identities | ||

| Female | 85% | 68 |

| Male | 10% | 8 |

| Other | 18.75% | 15 |

| Prefer not to say | 1.25% | 1 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 78.75% | 63 |

| Other | 22.5% | 18 |

| Prefer not to say | 5% | 4 |

| Racial/ethnic identities | ||

| Black | 3.8% | 3 |

| Caucasian | 79.75% | 63 |

| Indigenous | 8.86% | 7 |

| Other racialized | 10.13% | 8 |

| Prefer not to say | 2.53% | 2 |

| Prefer to self-describe | 5.06% | 4 |

| Disability | ||

| Yes | 15% | 12 |

| No | 85% | 68 |

| Prefer not to say | 0% | 0 |

a Out of total 155 survey respondents, only 80 responded to demographic questions.

b Respondents were asked to select all options that applied to their circumstances. The demographic data was intended to capture the multiple roles and identities of respondents in FE, resulting in higher than 100% response rate for some questions.

The Most Significant Challenges in Field Education: Qualitative Responses

Based on the qualitative data, seven themes were identified as the most significant challenges experienced in social work field education: lack of preparation, support, and training; burden of multiple responsibilities and roles; communication and supervision challenges; administrative challenges; COVID-related changes to online learning and practice; equity, diversity, inclusion, and access (EIDA); and competition and perceived unfair placement selection procedures. Each theme is discussed in the next section.

Lack of Preparation, Support, and Training

Research participants described the lack of preparation, support, and training as one of the most significant challenges in social work field education in Canada. Students and field educators reported receiving insufficient training, support, and resources from schools and field agencies to support their role in field education. In exemplifying the lack of support from institutions, one respondent said, “[Students had trouble having] access to specific courses in a second-degree program” (Respondent 79, Q2). This theme was echoed by another participant, who stated that the field agency sometimes failed to offer students the necessary preparation and support for them to complete their work. A few students also felt unsupported by their field educators. The following excerpt illustrates this concern: “Field educators have high expectations but do not train or guide students and are looking for students to help them in their overwhelming job as opposed to designating time to train students” (Respondent 37, Q9). Respondent 8 agreed with the sentiment of Respondent 37, as she reported that field educators regarded students “like additional helping hands, with minimal support from educators” (Q2). Lack of support was of concern to students, as they felt they were not prepared enough to work independently in the field.

Field educators more frequently reported that lack of student preparedness and readiness for placement posed major challenges to the quality of field education. These challenges were noted with a comment on students not showing enough initiative to improve or to complete assigned tasks. A respondent shared this perception: “I find that sometimes the students are not prepared and do not take the initiative to help grow their knowledge” (Respondent 77, Q2). Further, another respondent stated, “I have experienced challenges when we are given a student who is not at the level expected and are sometimes defiant towards the requirements set out by the school (i.e., completing weekly logs)” (Respondent 81, Q2). Faculty liaisons also identified preparation- and support-associated challenges. As indicated by a survey respondent, “a major difficulty is understanding the practice context of the agencies where students are working in their practicum” (Respondent 2, Q2).

Burden of Multiple Responsibilities and Roles

The study participants identified that the burden of multiple responsibilities and roles was one of the challenges that negatively affected the quality of social work field education in Canada. It was reported that most students, field education coordinators, directors, and field educators who had multiple commitments and responsibilities outside of field education experienced stress and burnout. Many of the participants discussed their struggles associated with finding enough time to complete all their tasks at home, at school, and at work. For example, Respondent 24 expressed worry about juggling multiple tasks: “It was challenging to find time to provide adequate supervision and mentoring to students when also fielding one’s own work” (Q2). According to the participants, this challenge negatively impacted their potential to fulfill their roles in field education and influenced the quality of service they provided to clients.

The financial burden associated with unpaid field placements was cited as an influencing factor that contributed to students’ multiple responsibilities. One respondent commented, “Unpaid placements for many students meant working a full-time job without pay while still needing to pay tuition. This situation poses challenges to students in making ends meet or engaging in self-care” (Respondent 31, Q9). A similar sentiment was expressed by another respondent who stated that

Students often had to choose between their paid job and field placement. The lack of financial compensation may contribute to creating inequities for people who wish to enter the field of social work as only privileged people can pursue social work, perhaps contributing to the under-representation of some communities in social work. (Respondent 7, Q9)

Communication and Supervision Challenges

Lack of communication or ineffective communication was one of the most significant challenges participants consistently reported as negatively impacting field education in Canada. The channels of communication included those between faculty and field educators, between faculty and students, between the external field educator and their field agency (where the supervised students do their placements), and others. Many students expressed that they lacked a clear understanding of the processes of field education because they perceived the university did not provide enough information. Similar sentiments were expressed by field educators, indicating they found it difficult to supervise students since the tasks and expectations were not adequately explained. For example, a field educator expressed,

I was given no information about what the student could do, what the expectations were, or what I would need to get her set up. It really took a good few weeks to get everything ironed out, and I do not feel this should be the field educator’s responsibility. (Respondent 89, Q2)

The quantitative data showed that more than 50% of respondents were satisfied with the communication and liaison between the practicum office and field agency. Yet poor communication between field educators and students, which many students described as inadequate or even disappointing, was often cited by respondents as a supervision challenge. One respondent explicitly raised the challenge of communication when a student was supervised by multiple supervisors as follows: “Having multiple supervisors adds extra communication challenge to students with respect to “[not] develop[ing] much of a relationship with either of the supervisors” (Respondent 97, Q2). The importance of student–supervisor communication was also echoed by another student, who opined that

I think there need to be more dedicated spaces for supervision. I have lived experience in the system I’m working in, but there’s nowhere to debrief about that. My field instructor doesn’t get much supervision, so as a result neither do I. (Respondent 49, Q9)

Besides these challenges, many students reported a positive supervision experience during their field education (see Table 2). Considering both positive and negative communication and supervision experiences, participants agreed that having an open channel of communication among institutions, students, and supervisors could greatly improve the quality of field education in Canada.

Administrative Challenges

Field education coordinators/directors noted that recruiting qualified field educators and securing suitable field placements for students was their most significant administrative challenge. It was reported that this challenge negatively affected the quality of field education among students. For instance, many students indicated that their placements did not align with their learning objectives or career goals. The following excerpt illustrates the view of one student respondent regarding their most significant challenge: “Lack of ability to choose my placement. My placement was determined by a lottery system that does not reflect my learning or future employment goals” (Respondent 18, Q2).

COVID-Related Changes to Online Learning and Practice

COVID-19 and the resulting move to virtual learning were widely discussed by respondents to be among the most significant field challenges they experienced. It is important to note that the survey was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. Survey respondents reported high stress levels during the pandemic, making it more difficult for them to adapt to ever-changing COVID-19 restrictions and adjust the way they work and learn. In addition, working and learning from home on virtual platforms was perceived to create barriers for field educators and students to engaging in hands-on direct practice. For instance, field educators reported experiencing challenges supervising and supporting students online. Student respondents indicated that online field placements made them feel isolated, with very limited peer support, both emotionally and academically. Many worried about not having the same experiences as other graduates, which was perceived to potentially exclude them from many forms of future potential employment opportunities.

Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Access (EDIA)

Some study participants identified the lack of EDIA as a field education challenge. The concepts and guiding principles of EDIA aim to promote fair treatment and opportunities for all people. Challenges related to issues of EDIA in field education were articulated as mostly manifested through prejudice and discrimination (e.g., against one’s race, religion, sexual orientation, age, and ethnicity, etc.) that some students experienced in their interactions with field educators or agency stakeholders. One respondent remarked:

I experienced discrimination from a field education coordinator on the basis of my religion. In our short, 20-minute meeting to determine what placements I would be interested in, she spent around half the time asking me questions about my relationship to my faith. I felt judged and felt she believed my faith to be a barrier to me being a good social worker. (Respondent 28, Q5)

Some respondents expressed the concern that they were unfairly or inequitably treated in field education. It was noted by some of the participants who felt oppressed in field education that they found it hard to voice their concerns, given the power imbalance within the traditional student–supervisor dyad. One notable barrier for concerned students in advocating for EDIA was the fact that they relied on their field educators to evaluate their performance in the mandatory field education practicum. The study identified the demographic attributes and concerns of several study participants who expressed the view that they experienced discrimination in their field education.

Four of the participants attributed their young age to the reason that they experienced discrimination. One respondent said that “My skills and abilities were disrespected due to age” (Respondent 68). The respondents consistently described how “looking young” or “at a young age” had a negative connotation regarding their capacity. Three respondents reported that they were discriminated in their field placement because they were Black. One Black respondent reported that “I have experienced microaggressions in my field placement.” (Respondent 93, Q2).

Furthermore, two participants expressed the view that they were discriminated against through verbal harassment due to their physical appearance in terms of body weight and shape, or their appearance in general. One respondent claimed that a supervisor narrated encountering harassment from a supervisor who labeled the student as “sticks,” referring to how the student’s legs looked. Other forms of discrimination expressed by the participants were targeted at sexual orientation, religion, health and mental health issues, or a disability such as visual impairment.

Competition or Unfair Practicum Placement Selection Procedures

Perceived competition for placements, and/or unfair practicum placement selection procedures, was one of the field challenges of concern to participants. The results of the study indicate that there is a perception of competition for placements among students that could, through inequitable access to more desirable placements, ultimately lead to an unfair advantage of some students over others regarding securing future employment. It was reported that students often compete for placements at agencies with more resources. A respondent highlighted this theme by saying that

There is a certain unspoken culture/precedent of students being offered work after their placement is complete. However, this does not happen for every student, and I do perceive slight competition between students in hopes of being considered for future work at the placement. I don’t know that this is a challenge that could be eliminated (competition for limited jobs is a reality!) but perhaps making it something that was okay to talk about openly would help. (Respondent 40, Q9)

The competition for placements was described as exacerbated for students in lower years, who felt they were unfairly treated. It was perceived that when placement sites took students based on their year of study, it deprived less experienced students in the lower years of valuable opportunities to grow and learn.

The results of the descriptive analysis of the closed-ended Likert Scale questions, which indicates the extent of the most significant challenges in field education, are presented in the next section.

The Most Significant Challenges in Field Education: Quantitative Responses

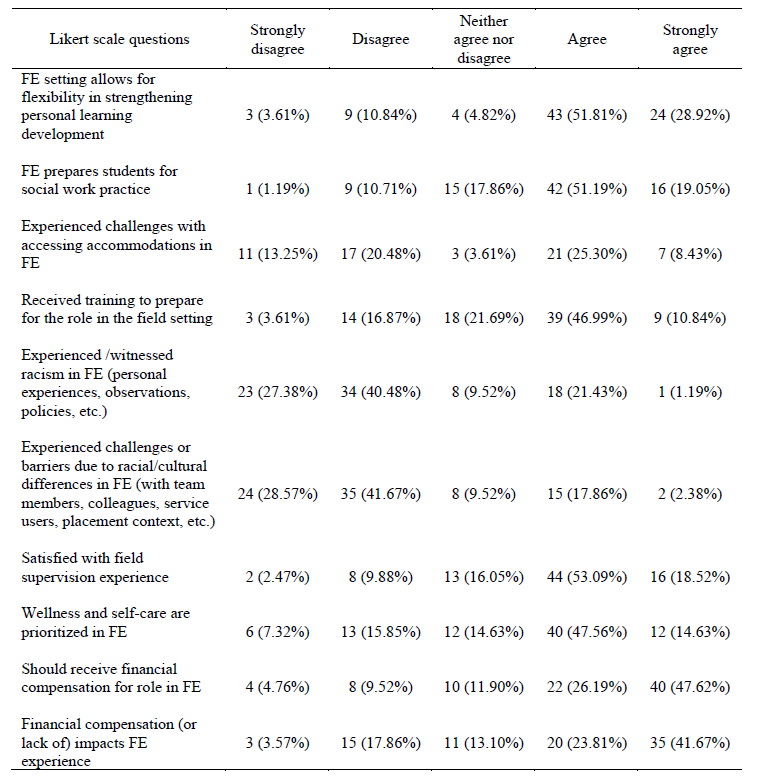

Table 2

Summary of Likert Scale Responses

In terms of flexibility in field education, out of 83 respondents, 43 (52%) agreed and 24 (29%) strongly agreed that field education provides flexibility for strengthening personal learning. In addition, out of 83 respondents, 39 (47%) agreed and 9 (11%) strongly agreed that they received training that helped them to feel prepared for their role in the field. However, 17 (21%) of respondents perceived that schools and field agencies did not provide sufficient training, support, and resources to support their role in field education. According to the survey, respondents’ perceptions about their ability to access accommodations in field education revealed that 28 (34%) of the respondents experienced difficulties accessing accommodations related to office space, computers, and religious and cultural holidays during field education. However, the other 28 (34%) of the respondents disagreed that they faced accommodation challenges. The survey also examined perceptions of discrimination as a challenge or barrier in field education. Approximately 60 (71%) of respondents agreed that they had not encountered racism in field education or faced challenges or barriers due to racial or cultural differences. Only 17 (20%) of respondents reported they faced challenges or barriers because of racial or cultural differences.

Regarding respondents’ satisfaction with field supervision and wellness and self-care in field education, most respondents agreed (44, 53%) or strongly agreed (16, 19%) that they were satisfied with their field supervision experience. Similarly, most respondents agreed (40, 48%) or strongly agreed (12, 15%) that wellness and self-care were prioritized in field education.

The survey also examined the impact and perceptions of financial compensation in relation to individuals’ role in field education. To these questions, almost half of the respondents (40, 48%), strongly agreed, and over a quarter of the participants agreed (22, 26%), that they should be financially compensated. Similarly, 35 (42%) of the respondents strongly agreed, and 20 (24%) agreed that financial compensation (or lack thereof) impacted their experience in field education.

Discussion

Our study contributes to the growing body of literature that focuses on the experiences and challenges facing social work field education in Canada to inform the development of proactive and sustainable field education models and practices. It is one of the few Canadian national studies to identify significant challenges facing social work field education from the perspective of field education coordinators, directors, faculty liaisons, field educators, and students (Tam et al., 2018). Seven significant challenges that were perceived to compromise the quality of social work field education in Canada were identified and are discussed in this section.

Social work students participate in field education as part of their academic program in order to develop their capacity to integrate theoretical and conceptual classroom learning into their practice in the field. Several students and field educators reported a lack of support, training, and resources from institutions and field agencies that undermined their supervisory role and acquisition of social work skills. On a micro level, field educators and students shared complaints about each other regarding these challenges. Students commented that field educators had high expectations and used them to help perform the educators’ own overwhelming tasks that were contrary to students’ learning objectives. Field educators, meanwhile, noted that students did not take initiative and did not perform tasks at the expected level, preventing them from achieving their learning objectives. This clearly demonstrates a need to enhance social work field education preparation among students and field supervisors in Canada. Fox and Higgins (2018) suggested investing in research programs that can support evidence-based strategies to enhance the quality of students’ and field supervisors’ preparation, support, and training models. These strategies can be imbedded in field education preparation seminars, specialized courses, assignments, and training of field supervisors (Fortune et al., 2018; Nedegaard & Carlin, 2021) or delivered as stand-alone models.

Various supervision models—such as Indigenous field education and antiracist models, policy development and staffing models, near-peer mentorship, etc.—have been developed to prepare students for social work field education. One promising model is simulation-based learning. A study from the University of Toronto suggests that feedback from simulation-based learning has the potential to improve students’ preparation for field education (Kourgiantakis et al., 2019). At the University of Oklahoma, it was found that using field labs in conjunction with simulation was associated with social work students’ adequate preparation for their first field placement (Bragg et al., 2020). In a study conducted at the University of Calgary, using role play had positive outcomes in terms of preparing students for social work field education (Allemang et al., 2021).

While it is important to utilize supervisory training models, this study also identified structural concerns, such as a lack of resources (lack of staff resulting in work overloads, lack of physical space and computers), a lack of accountability regarding student learning, and a lack of agencies’ taking responsibility for providing adequate support and resources for field education. Bogo et al. (2017) also identified these challenges and attributed them to structural problems within agencies. Supervision and support should not be overlooked as areas in need of improvement, as they still reportedly pose challenges for many respondents, demonstrating a need to enhance social work field education in this regard.

Field educators indicated a lack of student initiative, which could be the result of unpaid field training in social work. Many students reported being burdened by multiple responsibilities, which forced them to compromise on the achievement of quality field education. The study results support the field education literature; Hemy et al. (2016) reported students experiencing financial hardship and having to work additional jobs while completing their studies (Ryan et al., 2011). These financial hardships not only affected their education but also impacted them psychologically. Collins et al. (2010) reported that students commonly experience fatigue and emotional exhaustion due to feeling overwhelmed. There is a need to think more creatively about how to design social work field education programs and supervision models that can reduce the burdensome workload.

Our study also concurs with the literature that suggests field placement acts as a stressful burden for social work students, as most of them find it challenging to balance unpaid field placements with full- or part-time work and course work (Morris et al., 2022). Having multiple responsibilities has been reported to undermine students’ application of key social work values and skills in practice, compromising the quality of their education. Therefore, there is a need for social work education institutions to develop sustainable social work field education that considers students’ financial needs.

Many students reported a lack of communication with field educators, as well as between universities and agencies, preventing them from establishing strong working relationships with their supervisors. Furthermore, field educators and students indicated that, due to a lack of communication, they were unable to access adequate information and guidelines from both universities and agencies, which negatively impacted their learning. According to Vassos et al. (2018), one of the responsibilities of social work field education is to inculcate and develop effective communication skills in students, as such skills are central to the practice of social work. This study indicates that students and field educators, as well as field liaison faculty members, should have a strong and effective supervisory relationship, grounded in effective communication. It is, therefore, of paramount importance for social workers to identify ways to communicate effectively. Students’ communication skills can be developed by focusing on this in the social work curriculum or prepracticum training.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, social work field education shifted from in-person to online. Many respondents reported having difficulties adapting to the change. According to many respondents, it hindered their learning. Students were unable to engage in hands-on direct practice, and field educators found it challenging to supervise and support students online. The study findings support the literature, in which the pandemic was shown to significantly impact the social work field education landscape in Canada and globally (Dempsey et al., 2022; Drolet et al., 2020; Morley & Clarke, 2020). Institutions, field educators, and students had to rapidly adapt to the evolving circumstances presented by the pandemic with no preparatory training. It is also acknowledged that there were limited academic and mental health supports from institutions as well as from peers. As a result, pandemic-related stress and challenges were heightened, as teaching and learning at home via virtual platforms created barriers for field educators and students. Due to imposed restrictions, many field education opportunities were removed or shifted to remote settings. Many students felt their online training was insufficient in comparison with those who received in-person training before the pandemic, which may negatively impact their future employment opportunities. Ashcroft et al. (2022) also found the pandemic negatively impacted social workers in multiple ways, one of which was limiting employment opportunities for recent graduates. Remote learning and practice will likely continue beyond the pandemic (Ashcroft et al., 2022); therefore, more research is needed to ascertain optimal online approaches and provide students with quality online field education opportunities.

Several respondents reported experiencing discrimination in their field education due to factors such as age, race, physical appearance, disability, sexual orientation, and religion. They perceived inequitable treatment in field education, which made them feel oppressed. Previous studies have addressed these challenges (Gair et al., 2015; Razack, 2002). Several students in this study also reported that they preferred to remain silent in the face of discrimination, due to a power imbalance within the traditional student–supervisor dyad. Students were fearful that field educators might unfairly use their power in retaliation, negatively affecting the students’ performance evaluations for their mandatory field education practicum. The results of this study clearly indicate that students and educators must learn more about antioppressive practices in field education. Bhuyan et al. (2017) found that graduates have limited opportunities to learn about antioppressive practices and social justice theories in their field education.

Although this study identified various perceptions of field challenges, we also note that many racialized students, staff, and faculty experience additional barriers and challenges within their respective roles in social work. More specialized research is needed, as well as intentional systemic and institutional changes, to address these gaps and other barriers that differently abled bodies and various identities face in social work field education.

Finally, our findings, along with those of other studies in Canada, show that social work education not only involves competition for financial resources but also for practicum placements (Archer-Kuhn et al., 2020). The competition to secure a placement perceived among students is due to various pressures in the social work field. The practicum placement selection procedures were reported as unfair, as some placement sites take students based on their year of study. This can deprive less experienced students of valuable opportunities to foster their learning. Overall, the competition for a placement and lack of suitable placements (commensurate with student level and learning needs) are posited to be a consequence of neoliberalism and consumerist approaches, which limit meaningful engagement with practice experiences, hindering the development of the next generation of social workers.

Limitations of the Study

There were several notable limitations to this study. As this study is specific to Canadian social work field education and captured only the experiences of respondents affiliated with CASWE-ACFTS–accredited universities, the findings cannot be generalized to social work certificate and diploma programs or to social work programs in other countries. However, the challenges experienced may resonate with the global social service workforce.

Further, the lack of diversity in the demographic makeup of respondents is notable (see Table 1). The sample comprised a balance of students and field educators, which helped to strengthen our study findings, as representative perspectives were offered from multiple roles within social work field education. There was a significant lack of geographic representation across the sample, which predominantly represented Newfoundland and Labrador, Alberta, and Ontario, with some provinces and territories yielding little or no responses. It is also important to note that the study demographic was primarily female, heterosexual, and white. As such, the findings are not representative of all populations and identities within Canadian social work field education. The findings are also based on the perceived experiences and challenges of field education across Canada.

The survey was made available online for approximately three weeks, which may be a potential limitation in terms of obtaining a comprehensive understanding of all field challenges experienced in social work field education in Canada; a longer data collection period may have provided more survey responses. The high rate of skipped responses in the survey is a limitation. Respondents were permitted to skip questions and answer only certain ones. Although all questions were examined to ensure that respondents could answer every question depending on their status (as students, field educators, and administrators), it is possible that some respondents skipped questions that they deemed not applicable to them. Consequently, the findings for each question are based solely on the respondents who chose to respond, which makes it difficult for the researchers to conclude that all respondents are equally represented regarding each question. The survey was conducted during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have exacerbated some of the issues discussed. Therefore, when interpreting the study’s results, one should consider the pandemic’s influence. Despite these limitations, the study obtained comprehensive and enriching responses that were beneficial for a critical examination of Canadian social work field education.

Conclusion

Our survey findings provide information on the most common and significant challenges experienced by numerous stakeholders in field education. Program planning, policy development, and institutional change are needed to address the challenges identified. This will require commitment and collaboration with multiple stakeholders, including students, CASWE-ACFTS–accredited universities/faculties, and Canadian social work regulatory bodies. Future research should explore more comprehensive and diverse understandings of the challenges experienced in Canadian social work field education, which we believe will allow for the development of more sustainable and innovative field education models in the future.

References

Allemang, B., Dimitropoulos, G., Collins, T., Gill, P., Fulton, A., McLaughlin, A.-M., Ayala, J., Blaug, C., Judge-Stasiak, A., & Letkemann, L. (2021). Role plays to enhance readiness for practicum: Perceptions of graduate & undergraduate social work students. Journal of Social Work Education, 58(4), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1957735

Allen, M. D., & Trawver, K. (2012). Student mental health and field education: Responsibilities and challenges of field. Field Educator, 2(1), 1–5.

https://www2.simmons.edu/ssw/fe/i/Dallas%20Allen.pdf

Archer-Kuhn, B., Ayala, J., Hewson, J., & Letkemann, L. (2020). Canadian reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic in social work education: From tsunami to innovation. Social Work Education, 39(8), 1010–1018.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1826922

Ashcroft, R., Sur, D., Greenblatt, A., & Donahue, P. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social workers at the frontline: A survey of Canadian social workers. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(3), 1724–1746.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab158

Ayala, J., Drolet, J., Fulton, A., Hewson, J., Letkemann, L., Baynton, M., Elliott, G., Judge-Stasiak, A., Blaug, C., Tétreault, A. G., & Schweizer, E. (2017). Field education in crisis: Experiences of field education coordinators in Canada. Social Work Education, 37(3), 281–293.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1397109

Banks, S., Cai, T., de Jonge, E., Shears, J., Shum, M., Sobocan, A. M., Strom, K., Truell, R., Uriz, J., & Weinberg. (2020). Practising ethically during COVID-19: Social work challenges and responses. International Social Work, 63(5), 569–583.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820949614

Barsky, A. (2019). Technology in field education: Managing ethical issues. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 37(2-3), 241–254.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2019.1578326

Bernard, C. (2013). Anti-racism in social work practice [Review of the book Anti-racism in social work practice, by A. Bartoli, Ed.]. The British Journal of Social Work, 43(8), 1672–1673.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct204

Bhuyan, R., Bejan, R., & Jeyapal, D. (2017). Social workers’ perspectives on social justice in social work education: When mainstreaming social justice masks structural inequalities. Social Work Education, 36(4), 373–390.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1298741

Bogo, M. (2006). Field instruction in social work: A review of the research literature. The Clinical Supervisor, 24(1-2), 163–193.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v24n01_09

Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices and contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 317–324.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

Bogo, M., & Globerman, J. (1995). Creating effective university–field partnerships: An analysis of two interorganization models of field education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 12(1-2), 159–174.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v12n01_11

Bogo, M., Lee, B., McKee, E., Ramjattan, R., & Baird, S. L. (2017). Bridging class and field: Field educators’ and liaisons’ reactions to information about students’ baseline performance derived from simulated interviews. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(4), 580–594.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1283269

Bogo, M., Sewell, K. M., Mohamud, F., & Kourgiantakis, T. (2020). Social work field education: A scoping review. Social Work Education, 41(4), 391–424.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1842868

Bragg, J. E., Adamson, T., McBride, R., Miller-Cribbs, J., Nay, E. D. E., Munoz, R. T., & Howell, D. (2020). Preparing students for field education using innovative field labs and social simulation. Field Educator, 10(2).

https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/preparing-students-for-field-education-using-innovative-field-labs-and-social-simulation/

Cameron, P. J., & Este, D. C. (2008). Engaging students in social work research education. Social Work Education, 27(4), 390–406.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470701380006

Carey, M. E., & McCardle, M. (2011). Can an observational field model enhance critical thinking and generalist practice skills? Journal of Social Work Education, 47(2), 357–366.

https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2011.200900117

Collins, S., Coffey, M., & Morris, L. (2010). Social work students: Stress, support and well-being. The British Journal of Social Work, 40(3), 963–982.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcn148

Cox, D. C., & Burdick, L. E. (2001). Integrating research projects into field work experiences: Enhanced training for undergraduate geriatric social work students. Educational Gerontology, 27(7), 597–608.

https://doi.org/10.1080/036012701753122929

Dempsey, A., Lanzieri, N., Luce, V., de Leon, C., Malhotra, J., & Heckman, A. (2022). Faculty respond to COVID-19: Reflections-on-action in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(1), 11–21.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00787-y

Drolet, J. L., Alemi, M. I., Bogo, M., Chilanga, E., Clark, N., Charles, G., Hanley, J., McConnell, S., McKee, E., St. George, S., & Wulff, D. (2020). Transforming field education during COVID-19. Field Educator, 10(2).

https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/transforming-field-education-during-covid-19/

Drolet, J., & Harriman, K. (2020). A conversation on a new Canadian social work field education and research collaboration initiative. Field Educator, 10(1), 1–7.

https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Conversation_10.1-1.pdf.

Fortune, A. E., Rogers, C. A., & Williamson, E. (2018). Effects of an integrative field seminar for MSW students. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(1), 94–109.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1307149

Fox, M., & Higgins, M. (2018). Theory mapping in social work placements: The KIT model applied to meso and macro practice tasks. Advances in Social Work & Welfare Education, 20(1), 209–214.

https://www.anzswwer.org/wp-content/uploads/Advances_Vol20_No1_2018_Chapt13.pdf.

Gair, S., Miles, D., Savage, D., & Zuchowski, I. (2015). Racism unmasked: The experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in social work field placements. Australian Social Work, 68(1), 32–48.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.928335

Hemy, M., Boddy, J., Chee, P., & Sauvage, D. (2016). Social work students “juggling” field placement. Social Work Education, 35(2), 215–228.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1125878

Kourgiantakis, T., Sewell, K. M., & Bogo, M. (2019). The importance of feedback in preparing social work students for field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(1), 124–133.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0671-8

Morley, C., & Clarke, J. (2020). From crisis to opportunity? Innovations in Australian social work field education during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Social Work Education, 39(8), 1048–1057.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1836145

Morris, B., Todd, S., & Kalmanovitch, A. (2022). When the going gets tough: Case studies of challenge and innovation in Canadian field education. In R. Baikady, S. M. Sajid, V. Nadesan, & Islam, M. R. (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of field work education in social work. Routledge.

Nedegaard, R., & Carlin, A. (2021). Innovations to the design and delivery of foundation field education seminars. Field Educator, 11(1).

https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/innovations-to-the-design-and-delivery-of-foundation-field-education-seminars/

Razack, N. (2002). Transforming the field: Critical antiracist and anti-oppressive perspectives for the human services practicum. Fernwood Publishing.

Ryan, M., Barns, A., & McAuliffe, D. (2011). Part-time employment and effects on Australian social work students: A report on a national study. Australian Social Work, 64(3), 313–329.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2010.538420

Srikanthan, S. (2019). Keeping the boss happy: Black and minority ethnic students’ accounts of the field education crisis. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(8), 2168–2186.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz016

Tam, D. M. Y., Brown, A., Paz, E., Birnbaum, R., & Kwok, S. M. (2018). Challenges faced by Canadian social work field educators in baccalaureate field supervision. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 38(4), 398–416.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2018.1502228

Transforming the Field Education Landscape (TFEL). (2020). About the TFEL project. https://tfelproject.com.

Vassos, S., Harms, L., & Rose, D. (2018). Supervision and social work students: Relationships in a team-based rotation placement model. Social Work Education, 37(3), 328–341.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1406466

Walsh, J. J., Drolet, J. L., Alemi, M. I., Collins, T., Kaushik, V., McConnell, S. M., McKee, E., Mi, E., Sussman, T., & Walsh, C. A. (2022). Transforming the field education landscape: National survey on the state of field education in Canada. Social Work Education,

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2056159

Wayne, J., Bogo, M., & Raskin, M. (2006). The need for radical change in field education. Journal of Social Work Education, 42(1), 161–169.

https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2006.200400447

Wayne, J., Bogo, M., & Raskin, M. (2010). Field education as the signature pedagogy of social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(3), 327–339.

https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2010.200900043