Abstract

The SWEAP 2015 Field Placement/Practicum Assessment Instrument is a standardized measure of student attainment in field practicum/placement, designed to align with the 2015 Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards of the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE, 2015). The tool is used by field instructors in undergraduate social work programs and in the generalist year of graduate programs to assess student competency across the nine CSWE Core Competencies. Analysis of data on 4,209 students from 66 undergraduate social work programs and 795 generalist-year master’s-level social work students from 10 graduate programs supports the reliability, validity, and utility of the instrument.

Introduction

The field practicum provides the opportunity for social work students to apply and practice the skills they have learned through their social work curriculum. The Council on Social Work Education’s (CSWE) 2008 Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS) declared field education as the “signature pedagogy” of social work education (CSWE, 2008). That designation for field education continued with the 2015 CSWE EPAS (CSWE, 2015).

Social work program faculty are ultimately responsible for designing and implementing field placements that meet EPAS requirements in order to secure and continue CSWE accreditation. Social work programs are also responsible for evaluating students’ performance in field and reporting the results to CSWE as part of their accreditation, reaffirmation, and regular assessment reporting processes.

The Field Placement/Practicum Assessment Instrument (FPPAI) is one of six instruments that make up the Social Work Education Assessment Program (SWEAP) instrument package (SWEAP, 2015). The current SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is designed specifically as a standardized tool for undergraduate and graduate social work programs to address the requirements outlined by the 2015 EPAS. The purpose of the present study is to evaluate the reliability and validity of this most recent version of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI.

Review of Literature

Signature Pedagogy: Field Education

A student’s first exposure to the standards of social work practice is often located in the explicit curriculum of the social work program. Moving through the explicit curriculum while simultaneously participating in a field placement offers students the opportunity to apply in practice concepts learned through the explicit curriculum (Bogo, 2015). Field education offers students the opportunity to transfer the theoretical concepts and social work skills learned in the classroom to an actual social work setting under the guidance of a field instructor (Boitel & Fromm, 2014). Thus, the field education experience provides a vital time and place for students to practice becoming a “social worker” (Bogo, 2015).

A longitudinal study considering the learning patterns of undergraduate social work students found that field education fostered a deeper understanding of professional knowledge and skills (Lam et al., 2018). After field education the study’s participants were able to make meaningful and deep reflective consolidation of learning (Lam, et al., 2018).

Measuring Student Educational Outcomes in the Field Setting

There are many considerations for designing a field evaluation instrument. Factors involved in measuring student competency within the practicum setting are complex, and include the field setting, the learning contract, the field instructor, and the student. This complexity can often mean diverse, or even conflicting, foci for a field instructor’s evaluation of students.

The volunteer nature of the field instructor role, the readiness of students who are increasingly pulled in many directions, pressures for accountability, and/or a desire to be a mentor and not an evaluator are among the multifaceted challenges facing field instructors as they consider assessment of students (Gushwa & Harriman, 2018). Field instructors have been known to express leniency bias in their evaluations (Vinton & Wilke, 2011) resulting in concern that the practice is fraught with grade inflation (Sowbel, 2011). As the number of social work students, and social work programs, has increased over time, the challenges of evaluating student outcomes in field have become more pronounced (Gushwa & Harriman, 2018).

The complex nature of student evaluation in the field setting makes it challenging for social work programs to find an appropriate assessment measure as they continue to strive to attain or retain their CSWE accreditation (Boitel & Fromm, 2014). Starting in 2008, educational standards in social work shifted focus to competency-based outcomes from previous standards that ensured the curriculum covered certain professional concepts and theories. The design of assessments related to student outcomes evolved in response. There continues to be considerable variation in how student competency is evaluated between individual social work programs (Cleak et al., 2015; Regehr et al., 2011, 2012; Sellers & Neff, 2019).

The field placement setting is the ideal place to assess social work students for professional competency (Wayne et al., 2010). CSWE’s EPAS 2015 requires two assessment measures for each of the nine Core Competencies in undergraduate programs and in the generalist practice curriculum of graduate programs, as well as for all competencies developed for the specialized practice curriculum of graduate programs. Section 4.0.1 of EPAS 2015 requires that one of these two measures evaluate students in a “real or simulated practice setting” (CSWE, 2015). Since the field practicum evaluation assesses students in a real practice setting, many programs opt to use this evaluation to meet the EPAS assessment criteria.

EPAS 2015 also requires that programs assess multiple dimensions of each competency. Dimensions, as defined by EPAS 2015, include “knowledge, values, skills, and cognitive and affective processes” (CSWE, 2015). The field evaluation, often designed with multiple items to assess various components related to each competency, is an ideal tool for providing multi-dimensional assessment.

One key aspect of developing an assessment of student learning outcomes involves considerations for data collection and instrumentation that impact instrument reliability and validity. Reliability refers to “the consistency or repeatability of your measures” (Trochim & Donnelly, 2006, Reliability section, para. 1). Validity refers to “the best available approximation of a given proposition, inference, or conclusion” (Trochim & Donnelly, 2006, External Validity section, para. 1).

Development of field measures at the school/program level can add to the difficulties in securing instrument reliability and validity. An examination of three such field evaluation tools developed prior to EPAS 2008 found that each included evaluation categories that were broad in nature, making it difficult to interpret the outcomes (Regehr et al., 2007). Other limitations of school/program-created instruments include lack of variability in student demographics across race, gender, and socioeconomic groups. Consequently, the literature has stressed the need for the development of standardized evaluation tools for use in the field practicum setting that are appraised for reliability and validity (Rowe et al., 2020; Christenson et al, 2015), and that include a large and diverse sample from multiple social work programs (Rowe et al., 2020). The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is such an instrument.

SWEAP 2015 FPPAI

Social Work Education Assessment Project (SWEAP)

The Social Work Education Assessment Project (SWEAP) team is currently made up of a diverse group of six social work educators from undergraduate and graduate programs across the country. This group, formerly known as the Baccalaureate Education Assessment Project (BEAP), was formed in the late 1980s to create instruments for use in internally and externally driven outcomes assessment. BEAP transitioned to SWEAP in 2013, reflecting the applicability of our instruments to graduate, as well as undergraduate, social work programs. Over the past 20+ years, 17 different social work educators have been part of the team.

The SWEAP team members have extensive experience in social work education, with particular expertise in field education. SWEAP team members have served as field directors, field liaisons, and/or field instructors across dozens of undergraduate and graduate social work programs. Three members have served as undergraduate or graduate social work program field directors, for a combination of over 16 years of service in that role. All members have served as field liaisons and field instructors over multiple academic years at both the BSW and MSW levels. Multiple SWEAP team members have also been BSW and/or MSW program directors, for a combined 17 years of experience, and were responsible for the development of successful self-studies in support of initial CSWE accreditation and program reaffirmation at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

Over 500 undergraduate and graduate social work programs have used BEAP and/or SWEAP instruments since their inception. Multiple undergraduate and graduate social work programs have successfully used SWEAP instruments towards CSWE initial accreditation and reaffirmation under EPAS 2015.

Purpose

The underlying purpose of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is to provide to social work programs a standardized and easily deliverable method of evaluating student competency at the generalist practice level, in an effort to inform effective program evaluation and meet CSWE accreditation requirements.

Design

The FPPAI was designed originally as a standardized instrument for evaluation of student outcomes in field education by the Social Work Education Assessment Project (SWEAP) in response to the 2008 EPAS. The tool was developed, piloted, and evaluated under the supervision of the SWEAP team, and found to be reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = r =.96) (Christenson et al., 2015). Content, construct, and concurrent validity were also supported by pilot data (Christenson et al., 2015). The FPPAI was later updated to its current version in response to 2015 EPAS and guidance gleaned from CSWE presentations at professional conferences and related trainings.

The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI was designed specifically to measure student attainment of each generalist practice competency outlined in EPAS 2015, as evaluated in real practice by their field instructor. As a measure of student achievement in a real practice setting, the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI meets the 2015 EPAS requirement of having one such measure.

The items for evaluation included in the most recent iteration of the FPPAI were selected to provide holistic assessment of the individual student’s “demonstration of the competencies and the quality of internal processing informing the performance” (CSWE, 2015, p. 18) observed by the field instructor. The FPPAI was designed more generally to identify the strengths and weaknesses of individual social work students in their practice within the field setting, while simultaneously providing a system to easily aggregate data for use in program-level assessment.

Each of the competencies is captured for assessment in operationalized definitions of behaviors. The behaviors used in the 2015 FPPAI are directly related to those outlined in EPAS 2015. Since some of the 2015 EPAS behaviors are multi-barreled, the FPPAI 2015 separates those behaviors into multiple items to allow for individual analysis.

The SWEAP FPPAI 2015 is designed to allow field instructors to provide quantitative evaluation of the student for each identified behavior. In addition to the quantitative portion of the FPPAI, field instructors can also contribute qualitative feedback through the FPPAI online instrument.

Administration

The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is administered exclusively through the SWEAP website. The instrument can be administered in a number of ways. Individual links to electronic instruments can be sent directly to field instructors through the SWEAP website, or these links can be emailed to field instructors through the SWEAP user email platforms. Programs can purchase a single-link option, where one uniform link can be sent by email, and/or integrated into field management systems for delivery. SWEAP can also work with programs to integrate individualized instrument links into their online field management systems, through a process called Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI). With LTI, faculty and program administrators can more easily oversee field instructor completion of the FPPAI as an assigned assessment.

Measurement

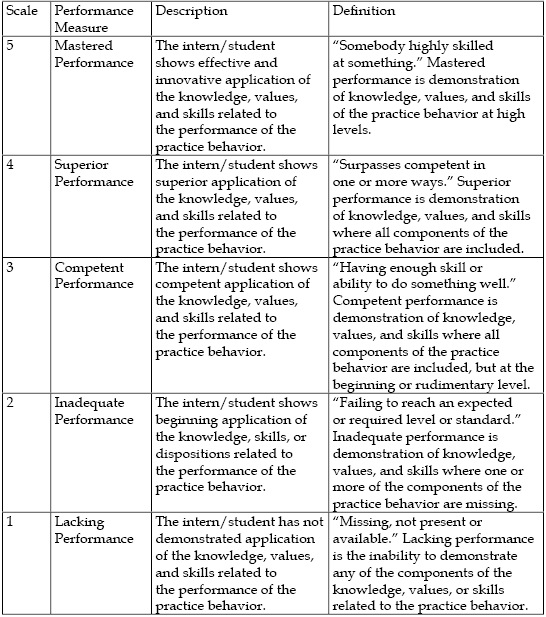

The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI contains 48 questions. All questions are written in Likert-scale format. The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI scale consists of five points ranging from lacking performance (1) to mastered performance (5). (See Table 1). This scale is different from that used in the FPPAI 2008, which had a 10-point scale. The final SWEAP 2015 FPPAI scale was developed from extensive literature research and recommendations from experts in assessment, including the SWEAP team members, during the piloting phase of the instrument, including information from the 2015 EPAS standards.

Table 1: FFPAI Likert Rating/Evaluation Scale

The previous 2008 version included a “not observed” (N/O) option. This option was removed after user feedback, and in consultation with the Council on Social Work Education. As reported by CSWE at professional conference presentations on assessment, student performance needs to be measured. If a student is lacking in the opportunity to show evidence of their competency, they are still lacking in that performance, and should be evaluated accordingly. The N/O option is, however, available to programs through the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI at the midpoint evaluation, as an add-on instrument customization, since midpoint evaluations are not reported in program assessment for accreditation purposes.

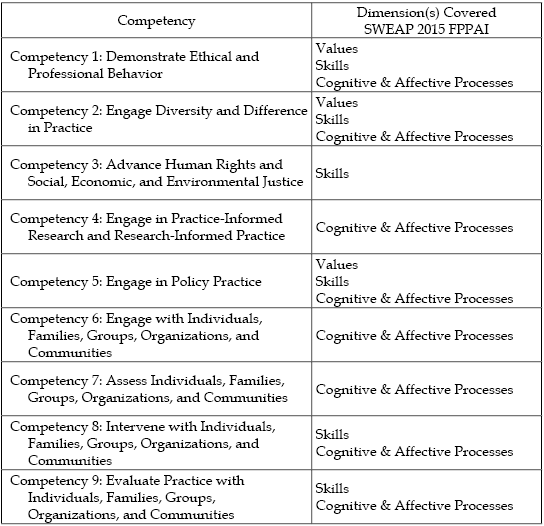

The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI supports multidimensional assessment required by EPAS 2015. Each SWEAP 2015 FPPAI item relates to one of the following dimensions: values, skills, or cognitive and affective processes. The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI does not assess student knowledge. SWEAP has separately constructed an instrument that assesses student knowledge. This instrument is the Foundation Curriculum Assessment Instrument. See Table 2 for a list of the dimensions covered for each competency on the FPPAI.

Table 2: CSWE Dimensions Covered by Competency on SWEAP 2015 FPPAI

The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI reporting is a two-stage process that is dynamic and user friendly for SWEAP users. When a field instructor submits the individual evaluation, an individual report is automatically created for the student as Microsoft Word and PDF files available in the user’s SWEAP account, and the data is stored for generating individual and aggregate outcomes reports. Once all field evaluations are completed for a given time period, the SWEAP user can run an aggregated outcomes report through the SWEAP website by selecting the completed instruments for which they want to run the report.

Once the program selects the parameters, the aggregated report is generated and automatically available in their SWEAP account. This aggregated report provides the requisite information for reporting assessment results in a self-study for accreditation or reaffirmation, as well as for contributing to the calculations necessary to keep a program’s website reporting requirement up to date in their AS4 forms. Programs that are interested in conducting a higher level of statistical analysis of their own field evaluation data can also access Excel or SPSS files of their aggregate raw data for their own analysis and reporting.

It is important to note, as reflective of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI rating scale, that the SWEAP team recommends that programs report student achievement of competency at an average rating of 3 for a given competency. As a result, SWEAP 2015 FPPAI reports automatically report the percentage of students who achieve an average rating of 3 in each of the nine competency areas.

Methodology

Study Design and Sample

The current study was designed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI. The data for this study included instrument results collected as part of generalist practice field placement evaluation of undergraduate and graduate students from 2015 to 2019. The sample included 4,209 students in 66 different undergraduate social work programs, and 795 generalist-year master’s level social work students in 10 different graduate programs.

Instrument Validation

Construct and Content Validity

The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI was designed to measure student performance of the nine competencies outlined in CSWE’s EPAS 2015. These competencies serve as the “constructs” that the SWEAP FPPAI seeks to measure. The SWEAP team used the language provided by CSWE for the competencies, and the associated behaviors, as the guide in crafting each item. There are two to nine items per competency. The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI was then presented to SWEAP users for feedback, and adjustments to language were made. Construct and content validity are supported by the origination of instrument language from CSWE EPAS, the inclusion of multiple items per competency, and via the process of expert panel recommendations and incorporation of user feedback.

Reliability Analysis: Internal Consistency

Responses on all 48 items from evaluations of 3,698 individual students were analyzed for internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha reliability test of internal consistency for the entire scale was calculated at 0.984, indicating excellent overall internal consistency (Morgan, Gliner, & Harmon, 2006). Cronbach’s alpha reliability test of internal consistency was also completed for each of the nine competencies, with items grouped as a construct. These statistics ranged from .89 to .99, indicating excellent internal consistency at the competency level as well. See Table 3 for the reporting of Cronbach’s alpha at the competency level for the total sample, as well as for BSW and MSW subsamples.

Table 3: SWEAP 2015 FPPAI Reliability Analysis, Internal Consistency

Discussion

The 2015 SWEAP FPPAI was developed to provide social work programs with a standardized assessment of student field placement outcomes that is responsive to CSWE’s EPAS 2015 (Sullivan et al., 2020). Prior successes in securing CSWE accreditation and reaffirmation using the 2008 FPPAI as an assessment tool informed the development of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI. The 2015 EPAS saw a shift in assessment focus to competencies evaluated as constructs, and away from the minutiae of examining individual practice behaviors. Therefore, the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is designed to measure student achievement in the field placement through items grouped in relation to a given competency. SWEAP 2015 FPPAI reports are designed to provide competency-level assessment, as well as individual item-level feedback, to inform program evaluation and improvement. The instrument’s reliability and validity, reported above, support the use of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI to measure student achievement at the competency level. Thus, it is not surprising that since 2015 dozens of undergraduate and graduate social work programs have successfully used the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI towards accreditation and reaffirmation.

Critical in the development and use of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is the responsiveness of this instrument to the changing role of assessment in social work education and in higher education in general. Social work programs both small and large experience numerous challenges, especially when it comes to assessment. As regional accrediting bodies have placed more pressure on colleges and universities to use data to support their student outcomes, the burden of developing tools and reporting assessment has fallen on already overburdened faculty and program administrators.

The role of “assessment coordinator” (and other titles) is often handed to untenured faculty, or at-will staff, with little (or no) experience in program evaluation. Many of these colleagues have risen to the task, successfully developing assessment instruments for their own programs and providing excellent reporting. Many others have utilized professional networking to “crowd source” ideas for assessment, in the interest of saving time and of not being alone in their process. Whether or not the program develops its own assessment tools, it is still left with the tasks of designing, running, and interpreting reports based on the data.

A major benefit of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is that the time and energy otherwise necessary for developing tools, collecting data, and calculating outcomes is done methodically in a system designed by experts in the field. By using standardized instruments through a mechanized and online process, program faculty and staff can focus instead on the bigger picture of using assessment findings to improve their programs and better support their students.

While the focus on assessment has increased in higher education, there continues to be a dearth of published research on the validation of field instruments (Christenson et al., 2015; Rowe et al., 2020). This current piece on validation of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is just one of a few validation studies published since the shift to competency-based education in the 2008 EPAS that the authors could find focused on social work field instruments (Christenson et al., 2015; Rowe et al., 2020; Wang & Chui, 2017). Validating instruments through evaluation of data from a single social work program is a major concern (Rowe et al., 2020). The SWEAP FPPAI provides the only validation evidence the authors could locate that includes data from multiple social work programs (Christenson et al., 2015; Rowe et al., 2020). Further research exploring the use of data collected using a singular instrument, but across multiple social work programs, is strongly recommended to improve the assessment scholarship related to the validity of field instruments.

Limitations

While the reliability and validity of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is supported through the present study, there are several limitations of the instrument that should be noted. Even though the sample was large, it cannot be assumed that the 5,000 students who completed the instrument are representative of students from all CSWE-accredited undergraduate and graduate programs. Consequently, the possibility of bias must be recognized.

There are barriers to the use of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI, most notably the expense (Rowe et al., 2020). SWEAP is a business, and the instruments, along with the reporting of student data, must be purchased. All SWEAP instruments are copyrighted, and thus unauthorized use of the instruments is punishable by applicable law. However, the cost incurred in the purchase of SWEAP instruments is, arguably, comparable to the level of service and expertise received from the products. When considering the expense of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI, one also needs to consider, in balance, the amount of time that the field staff of a social work program spends on the design of instruments, collection of data, and calculation of statistics to report on that data.

Another barrier to the use of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI involves technology. All SWEAP instruments are now only available online. As a result, all SWEAP instrument users need to have internet access in order to complete instruments. However, SWEAP instruments have been optimized for completion on personal computers as well as on mobile devices.

Since the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is responsive to the nine EPAS 2015 competencies, the instrument is only appropriate for use in the reporting of student outcomes data for undergraduate social work programs and the generalist practice experience of graduate social work students. Undergraduate programs with additional, program-defined competencies could still use the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI, and work with SWEAP to develop and operationalize a customized instrument to measure the additional competencies. Graduate programs can also work with SWEAP to develop and operationalize a customized instrument to measure program-defined competencies for the specialized practice level of student field work. Customized instruments, however, do require an added fee to reflect the work necessary by the SWEAP team to support the changes.

The authors acknowledge that EPAS standards as defined by CSWE change periodically, necessitating alterations to the instrument. Programs must therefore be careful to appropriately choose and interpret the version of FPPAI that is reflective of the current EPAS standards under which they are operating. Finally, even though the instrument anchors are defined objectively, it is possible that the individual cohorts may interpret and use the anchors differently. It is recommended that each program provide periodic training to their field instructors/supervisors regarding the use of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI to enhance consistency in reporting. Furthermore, programs should understand that the selection of the SWEAP 2015 FPPAI as a measure of their program outcomes brings with it an expectation that they will engage in such trainings.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The SWEAP team acknowledges that SWEAP instruments are not the only valid and reliable instruments available for use. The SWEAP 2015 FPPAI is just one of many such instruments. The beauty of the current process of accreditation and reaffirmation is that programs get to make their own informed decisions about what assessment tools to use.

As future attention is paid to the assessment of social work student achievement in field work, it will be important to evaluate and substantively address concerns such as inter-rater reliability and grade inflation. More generally, attention needs to be placed on exploring the process of assessment and on concerns in setting and “achieving” benchmarks (Sullivan et al., 2020).

Future research in the area should always focus on guiding undergraduate and graduate social work programs as they strive for effective translation of their program assessment into valuable program improvements. The SWEAP team is honored to join our colleagues in this process.

References

Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices and contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43, 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

Boitel, C. R., & Fromm, L. R. (2014). Defining signature pedagogy in social work education: Learning theory and the learning contract, Journal of Social Work Education, 50(4), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.947161

Christenson, B., DeLong-Hamilton, T., Panos, P., Krase, K., Buchan, V., Farrel, D., Harris-Jackson, T., Gerritsen-McKane, R., & Rodenhiser, R. (2015). Evaluating social work education outcomes: The SWEAP Field Practicum Placement Assessment Instrument (FPPAI). Field Educator, 5.1, 1–13. https://fieldeducator.simmons.edu/article/evaluating-social-work-education-outcomes-the-sweap-field-practicum-placement-assessment-instrument-fppai/

Cleak, H., Hawkins, L., Laughton, J., & Williams, J. (2015). Creating a standardised teaching and learning framework for social work field placements, Australian Social Work, 68(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.932401

Council on Social Work Education. (2008). Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards. https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Standards-and-Policies/2008-EPAS/2008EDUCATIONALPOLICYANDACCREDITATIONSTANDARDS(EPAS)-08-24-2012.pdf.aspx

Council on Social Work Education (2015). Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards. https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Accreditation-Process/2015-EPAS/2015EPAS_Web_FINAL.pdf.aspx

Gushwa, M. & Harriman, K. (2018). Paddling against the tide: Contemporary challenges in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47, 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0668-3

Lam, C. M., To, S. M., & Chan, W. C. H. (2018). Learning pattern of social work students: A longitudinal study, Social Work Education, 37(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1365831

Morgan, G., Gliner, J. A., & Harmon, R. J. (2006). Understanding and evaluating research in applied and clinical settings. Erlbaum.

Regehr, C., Bogo, M., Donovan, K., Lim, A., & Regehr, G. (2012). Evaluating a scale to measure student competencies in macro social work practice. Journal of Social Service Research, 38(1), 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2011.616756

Regehr, C., Bogo, M., & Regehr, G. (2011). The development of an online practice-based evaluation tool for social work. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(4), 469–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731510395948

Regehr, G., Bogo, M., Regehr, C., & Power, R. (2007). Can we build a better mousetrap? Improving the measures of practice performance in the field practicum. Journal of Social Work Education, 43(2), 327–343.

Rowe, J. M., Kim, Y., Chung, Y., & Hessenauer, S. (2020). Development and validation of a field evaluation instrument to assess student competency. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(1) 142–154.

Sellers, W. & Neff, D. (2019). Assessment processes in social work education: A review of current methods. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 39(3), 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2019.1610544

Social Work Education Assessment Project (2015). Field practicum placement assessment instrument. https://www.sweapinstruments.org/?page_id=2260

Sowbel, L. R. (2011). Gatekeeping in field performance: Is grade inflation a given? Journal of Social Work Education, 47(2), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2011.201000006

Sullivan, D., Krase, K., Delong-Hamilton, T., Harris-Jackson, T., Christenson, B., Danhoff, K., & Gerritsen-McKane, R. (2020). Setting appropriate competency benchmarks to support successful social work program assessment. Social Work Education: The International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1845644.

Trochim, W., & Donnelly, J. P. (2006). The research methods knowledge base (3rd ed.). https://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/index.php

Vinton, L. & Wikle, D. J. (2011). Leniency bias in evaluating clinical social work student interns. Clinical Social Work Journal, 39, 288–295.

Wang, Y., & Chui, E. (2017). Development and validation of the perceived social work competence scale in China. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516631119

Wayne, J., Raskin, M., & Bogo, M. (2010). Field education as signature pedagogy of social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(3), 327–339.