Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted social work education, but limited research exists on its long-term toll on field directors. Using a thematic approach, 16 field directors were interviewed to explore the question, “What are the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on social work field directors?” Themes that emerged included the power of the field community; a collective sense of fatigue; questions of perceived value; and the need to respond to agency and student challenges. The importance of field directors and issues of parity are discussed. Implications for higher education and the meaning of signature pedagogy are also explored.

Keywords: field directors; COVID-19; qualitative; community; signature pedagogy

The COVID-19 pandemic was first declared a public health emergency by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) on January 31, 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). On March 13, 2020, the United States declared a state of emergency due to the pandemics’ severity and magnitude (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], 2020). In response to this global pandemic, universities across the world swiftly transitioned to educating using virtual spaces (Fernandez & Shaw, 2020; Krishnamoorthy & Keating, 2021). This rapid reconfiguration of higher education dramatically disrupted entire systems predicated on traditional face-to-face delivery of content (Filho et al., 2021). This shift also added enormous responsibilities, an increased workload, and significant stressors to faculty jobs (Archer-Kuhn et al., 2020; Evans et al., 2021; Fay & Ghadimi, 2020; Leitch et al., 2021; McLaughlin et al., 2020; VanLeeuwen et al., 2021). Many faculty had little experience providing remote education or understanding virtual pedagogical best practices, which left them scrambling to move courses online while learning new software and technology (Casacchia et al., 2021; Leitch et al., 2021; Mahmood, 2021).

Over the past four years, countless mandates were instituted at the local, state, and federal levels in response to the various stages of the pandemic. Life has changed significantly over the course of the pandemic. Sheltering in place, social distancing, the use of face masks, vaccination requirements, frequent testing, quarantining, and a variety of other measures have been implemented to respond to this unprecedented situation. While these evolving orders have impacted many within higher education, those in social work field education have had to respond to these challenges in especially flexible and creative ways (Bright, 2020; Leitch et al., 2021).

Historically, social work education has relied heavily on in-person activities such as role playing, client simulations, and internship placements (Leitch et al., 2021; Melero et al., 2021). These activities deeply enrich professional skill development; however, there are gaps in access to technology, a lack of equitable resources, and archaic systems that prevent these from transitioning easily online (Archer-Kuhn et al, 2020; Leitch et al., 2021). While these challenges were present for many, there was a disproportionately negative impact felt by historically marginalized communities such as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) students (Gates et al., 2023; Murray-Lichtman et al., 2022). The pandemic also significantly disrupted, and in many cases terminated, internship placements for students (Archer-Kuhn et al, 2020; Dempsey et al., 2022; Evans et al., 2021; Morley & Clark, 2020). In response to these disruptions, field directors had to rapidly pivot the method in which the signature pedagogy of social work programs was conducted (Dempsey et al., 2022; McLaughlin et al., 2020).

While the federal COVID-19 public health emergency officially ended on May 11, 2023 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023), those within field education are still working to establish a new post-pandemic norm while integrating the updated EPAS requirements. A collective sense of shared trauma, high levels of student burnout, increased demands for virtual programs and internship placements, and workforce issues causing a lack of supervision have left many within field education grappling to adjust (Bender et al., 2021; Bonano-Broussard et al., 2023; Cederbaum et al., 2022; Davis & Mirick, 2021; Keesler et al., 2022).

Study Objectives

As field education seeks a new norm, it is important to acknowledge the toll the pandemic has taken on field directors. While substantial research exists regarding the impact the pandemic has had on social work education and the disruption to field, there is limited literature on the impact the pandemic has had on field directors. There is also a general lack of literature focusing on field directors specifically. This is concerning, as field directors are responsible for organizing, implementing, and evaluating the signature pedagogy of social work education (Council on Social Work Education [CSWE], 2008, 2015, 2022). To address this gap, this study sought to explore the question, “What are the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on social work field directors?” This research study has implications for social work programs, as field education is the signature pedagogy of social work education. Understanding field directors’ experiences throughout the pandemic, and now, as they move into a post-pandemic world while still deeply impacted by COVID-19, is critical to developing best practices in field education.

Method

A thematic approach to inquiry, utilizing an inductive method, was selected, as it provides a rich and detailed understanding of participants experiences, perceptions, and views of a particular phenomenon (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). This approach allows for the exploration of research participants’ perspectives to guide the themes identified (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006; King, 2004). Further, this approach allows for a deeper understanding of how participants construct meaning based on their unique experiences (Braun & Clarke, 2022). In a thematic analysis, the researcher becomes familiar with the data set; employs rigorous and systematic coding; generates initial themes; develops and reviews themes; refines, defines, and names themes; and shares the report (Braun & Clarke, 2022).

In qualitative studies, the researcher is the instrument (Padgett, 2017). As such, it is critical to disclose the author’s background. The author is a 43-year-old White female who has been a practicing social worker for 20 years and employed within higher education for 13 years. During the pandemic, the author was a faculty member within a department of social work at a midsize state institution, and transitioned courses to an online format. The author accepted a position within that institution as a field director during the pandemic and continued to teach, though in a reduced capacity. The author has had personal and professional stressors during the pandemic, and brings these lived experiences to this research. As with any practice-close research, it is important to note that the author comes to this research with an understanding of the role and the struggles some field directors may encounter, as well as an understanding of higher education. The author’s knowledge and experience are important to acknowledge, as there is a potential for preconceived thoughts or experiences to unduly influence analysis and discussion.

Participants

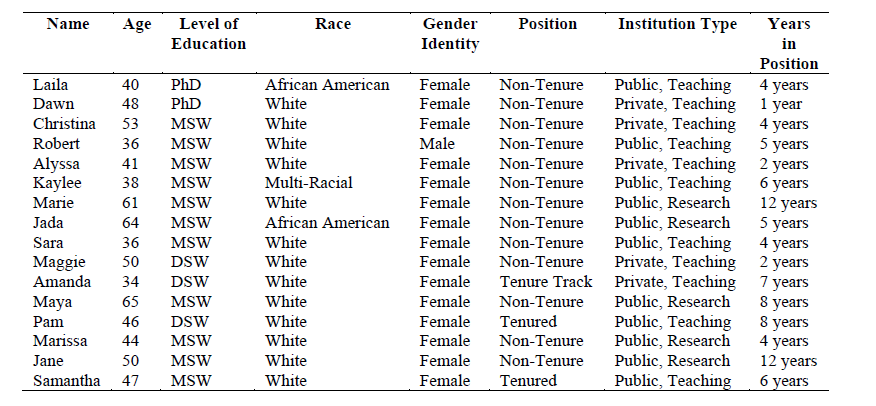

The sample consisted of 16 social work field directors from across the United States. The average age of participants was 47 years old (the youngest was 36 years old and the oldest 65 years old). Thirteen participants identified as White, two as African American, and one as multiracial. Fifteen participants identified as female and one as male. Eleven participants indicated their highest level of education was an MSW, while the remaining five indicated earning a PhD or DSW. Thirteen participants reported being in a nontenure staff or faculty role, two participants were in a tenure-track position but had not achieved tenure, and one was tenured faculty. The average length participants served as field director was 5.5 years (the shortest was one year and the longest 12 years). Six participants reported being employed at public teaching institutions, five at a private teaching institution, and five at an R1 university. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Demographics of Participants

Recruitment and Sampling

An invitation to participate in this study was sent to the CSWE Spark Field Directors Community as well as to two widely utilized social work faculty listservs: The Association of Baccalaureate Social Work Program Directors (BPD) and MSW-ED. Invitations for participation were posted in May 2022 and again in June 2022.

Participants were considered eligible to engage in the study if they were currently employed within a CSWE-accredited program and held the title field director or field coordinator. Purposive sampling was used, as the invitation was sent directly to each listserv, and to increase the response rate, snowball sampling was utilized as participants were encouraged to forward the invitation to colleagues (Rubin & Babbie, 2016). The study was approved by the author’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). No compensation was offered to participants.

Data Collection

Data were collected in a series of one-time interviews conducted via Zoom. Interviews began in June 2022 and concluded in August 2022. Participants engaged in a 15-question semistructured interview. Interview questions, and relevant probes, were constructed by the author. Prior to the interviews, a pilot test of the interview guide was conducted. Based on feedback, minor changes in the ordering of questions were made. Interviews were conducted in a private setting to ensure confidentiality. Participants were asked for demographic information, job responsibilities, and institutional information. Questions were included regarding how the pandemic initially impacted their role, as well as how their program adjusted and responded to the pandemic. Questions related to challenges and successes within their role during the pandemic; short- and long-term impacts of performing their responsibilities during the pandemic; and feedback they received from students, faculty, and agency supervisors regarding their experiences were also asked. Finally, participants were asked what they consider the biggest challenges facing field education.

Signed consent forms were obtained and all participants completed the interview, therefore attrition was not a factor. Interviews were transcribed and member checking occurred to ensure accuracy and to elicit additional comments. Interviews lasted 30 to 65 minutes, with an average interview time of 46 minutes. Data collection was ended after the sixteenth interview due to reaching saturation.

Issues of reflexivity were considered throughout this study. The author critically examined personal beliefs and experiences related to the pandemic and to working within field education during COVID. When discussing the impact of the pandemic, the author ensured objectivity through debriefing with a colleague, particularly after conducting interviews in which participants disclosed difficult or challenging situations. An audit trail of steps taken in data collection and analysis was kept and shared during this debriefing. To further solidify interview observations, including impressions and feelings, the author kept a reflexive journal which was used throughout the interview, coding, and writing process (Padgett, 2017).

Analysis

Each interview was transcribed using the Zoom transcription feature, and participants were given a pseudonym. The author listened to each recording and corrected discrepancies within the transcript. Each transcript was coded in its entirety. The author and a colleague engaged in an open coding process to increase levels of rigor, transparency, and trustworthiness (Nowell et al., 2017; O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). A code book was developed by each coder and consensus was reached when discussing themes that emerged (Padgett, 2017).

Findings

All participants reported experiencing significant stressors related to balancing work-life obligations during the pandemic. All participants experienced an increase in their workload and professional roles and responsibilities. As a result, participants identified feeling overwhelmed with the amount of work and the uncertainties related to the pandemic. All participants indicated significant challenges in placing and maintaining students in agencies, and worried about the overall rigor and experience of student internships. Each participant indicated varying degrees of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their institution’s response to the pandemic and the level of support they received.

After collecting and analyzing the data, four core themes emerged. These included the power of the field community; a collective sense of fatigue; questions of perceived value; and the need to respond to agency and student challenges. Each theme was present in all interviews and mentioned multiple times, with various examples provided below.

The Power of the Field Community

Often a field director is the only person, or one of only a few, assigned to practicum education. As such, this position can feel isolated and disconnected from the broader faculty. In response, field directors often form community and connection via listservs and through local and regional consortiums. These connections allow for field directors to share resources and bond with colleagues who understand the intricacies and uniqueness of their role. Through these relationships, informal and formal lines of support are often established. During the pandemic, the opportunity to connect in the traditional face-to-face method was not possible. To support the substantially increased challenges field directors faced, online communities and connection points were further utilized and became a lifeline for directors across the country.

A theme that emerged was the importance of the overwhelming support participants received from their field colleagues, field-specific listservs, and local and regional consortiums. All participants indicated receiving tangible support in the form of sharing resources. For example, Marie reported, “There was an increase in sharing resources and adding activities to our repositories. That support was a huge part of our success.” Marissa affirmed this sentiment, stating, “The material shared on the listservs helped us to develop a digital field lab. We still use it to this day. It was a great resource and we’ve shared it with all our students.”

Kaylee expressed a sense of gratitude for the connection with other field directors, indicating that “The community I found was instrumental in keeping me sane.” Laila reported, “When there was a problem, I had a team of field directors to go to. We didn’t have to do things by ourselves.” Maggie stated the level of support she felt from field directors across the country was “instrumental in creating a sense of community. They were collaborative and supportive. There were no signs of competition or territory. Everyone just shared and helped each other.” Pam sums up the power of this support by stating, “The camaraderie from colleagues was affirming and validating in an uncertain and scary time. It brought us back to our professional roots and served as a first step in uniting us as a profession.”

Collective Fatigue

Despite the sense of support and camaraderie found within the field community, participants reported an overall sense of fatigue. This overwhelming sense of fatigue during the pandemic led participants to feel stretched thin and exhausted. Maggie stated, “I think there is still a real COVID fatigue, and we are at our capacity right now. There has been no end that can be visualized.” Amanda echoed this sentiment, and stated, “I’m still so burnt out and tired. Everything just feels like a battle.” Samantha supported these statements, adding, “We ran around so long like chickens with our heads cut off. It just really took a toll on people and the stress is still there. It hasn’t gone away.”

Perhaps because of this sense of collective fatigue, participants indicated they noticed themselves, and their colleagues, becoming disconnected. Amanda stated, “I have spent so much time during the pandemic communicating. I’m exhausted. It just takes so much time and I find myself not wanting to put that much energy and effort into it.” Christina added, “It has been hard to connect. I just got so tired of Zoom and everything that now I’m burned out. I care about everyone but connecting takes a lot of energy that I don’t have.” Kaylee shared that she has noticed “a decline in student and faculty connectedness. Our interrelational skills are just lacking.” Pam stated, “I have seen a lot of faculty stop working with students because they are so tired and burned out. It has been so much.”

Questions of Perceived Value

More than half of participants expressed frustration regarding their overall employment status, experienced feeling devalued by their non-field colleagues, and felt their colleagues lacked an understanding of their role. Robert stated that during the pandemic he worked more hours with no extra compensation or support. “I just got things added to my workload and wasn’t compensated. If I were a tenure-track faculty, I would be paid, but because I’m staff, I get nothing.” Laila shared,

Across the board, our field staff are overworked, underpaid, undervalued, and understaffed, yet we are the signature pedagogy. We are constantly doing more with less and I think schools will start to see a real change as field folks retire or transition away from these positions. Without the right people in these positions, that stay long-term, we are not going to be able to meet the enormous challenges at hand.

Alyssa shared that she loves what she does, however, “My boss is the only one who gets what I do. No one else in my department even knows my role. They don’t understand field and don’t care to try.”

All participants expressed gratitude for the opportunity to share their perspectives and thanked the author for being interested in speaking to field directors. Dawn stated, “I’m grateful you are talking to field directors. I think a lot of people don’t focus on, or think about, field directors too much.” While all participants expressed a desire to share their perspectives, some voiced uncertainty about whether things would change in relation to how field directors are viewed and treated within higher education. Robert stated, “I’m not optimistic that things will change in academia. It’s all about research and power, and field directors don’t fall into that category.”

The Need to Respond to Agency and Student Challenges

Another theme that was shared in all 16 interviews was the unprecedented challenges agencies faced during the pandemic—and continue to grapple with—related to worker shortages. Jada stated, “The great resignation is a thing. There was, and still is, a revolving door of staff and supervisors everywhere, which is hard.” Marie added, “There has been huge movement and reorganization within agencies who are just to trying to keep up with client need and lack of workers.”

All participants mentioned the negative impact worker shortages have had on student internship experiences. Marissa explained, “It is hard when agencies are so short staffed. I struggle because I don’t know if students are getting the best experience and supervision. They probably aren’t.” Samantha supported this sentiment, stating, “Quality supervision is a huge issue. The availability and rigor of supervision when places are understaffed is a concern. This negatively impacts student learning.” Jane shared, “There is a lack of qualified field supervisors in agencies, and the supervisors we have are pulling double duty and often not receiving a workload reduction to supervise students.”

Agency flexibility in remote work was met with mixed feelings by participants. Kaylee stated, “People are working remotely. So now we have to contend with this and see if agencies, who are already short staffed, have the capacity to support internships. Supervision and not having someone at the agency is a real issue.” Marie shared, “People want to work virtually and that is leaving agencies with fewer people in the office.” Kaylee added, “We have always relied on volunteers and their good will to supervise students. This just isn’t sustainable especially when there are workforce shortages and people working remotely.”

Ultimately, the worker shortage is a double-edged sword. Field directors want agencies to have the time, energy, worker capacity, and resources to devote to providing students with a robust internship experience consistent with the values of the profession. However, many agencies are struggling to keep up with the increased demand and decrease in staff. Amanda stated,

There is such a shortage of social workers in the area and if agencies don’t take interns, we’re not going to change this. It is a terrible cycle. People are tired and they don’t have the energy to take interns when they are so busy and short staffed, but if they don’t, the situation won’t change.

Not only are field directors responding to significant changes within the agencies with whom they partner, but they are also grappling with the toll the pandemic and internship requirements have had on students and their mental health. Jada shared, “We have seen a lot more mental health issues with students. More students than ever before are not passing their internships.” Marie supported this statement:

We have seen an increase in students failing field, at a rate I’ve never seen. Our students have been sick or have lost someone to COVID. They are experiencing mental health crises and suffering a lot of loss. Many students are parents and caregivers, and this makes it hard to focus on their internships.

Jada shared, “Agencies are requesting more support from us because of the student mental health issues. These issues present as problems with professionalism in placement.” Sara states that she has become “more flexible and supportive with students. They just have so much on their plates and are struggling to navigate it all.” All participants shared the desire to support agencies and students, but acknowledged the lack of time, resources, and mental capacity as barriers. May stated, “We just keep being asked to do more, to shoulder this burden, and we aren’t given any support. It’s impossible to do everything.”

Discussion

Overall, the importance of the field community was reflected in each of the interviews. While networking, resource sharing, and support have always been instrumental to field director success, this was amplified during the pandemic. Participants shared that being able to communicate with other field directors across the country during this unprecedented time was critical to surviving the past few years. Participants described this sense of community as affirming and validating. This reduced stress and served as a lifeline for many in this role.

While such support was critical, participants shared challenges they faced, and expressed an overall sense of collective fatigue in managing and delivering the signature pedagogy of social work education due to the magnitude of the problems faced by agencies and students during the pandemic. Participants reported that agencies were facing unprecedented workforce shortages while experiencing an increase in clients accessing services. These challenges led to concerns regarding the student’s overall internship experience, particularly as it related to receiving quality supervision. Further, participants shared that student mental health issues skyrocketed during the pandemic, which often impacted their ability to fully engage in, and ultimately complete, their internship successfully. Field directors reported that the need to provide support to both groups stretched their capacity, which added to their sense of fatigue. Participants shared thoughts on the value their colleagues and institutions placed on the position of the field director. While the issues of equity, parity, value, and resourcing of field education have been topics of conversation for many years, participants indicated that disparities were highlighted during the pandemic.

Findings from this study as they relate to the nuances and unique challenges of the field director position are consistent with the literature. Field directors are responsible for organizing, implementing, administering, and monitoring the signature pedagogy of social work education, while understanding community needs and the best ways to respond to changes occurring within the profession (Ayala et al., 2018; Beaulieu, 2020; Ellison & Raskin, 2014; Lyter, 2012). They are expected to navigate complex and constantly changing landscapes within higher education, and serve as the institutional authority on the most critical part of the curriculum (Ayala et al., 2018; Lyter, 2012). Despite this instrumental role, many field directors feel undervalued, hold a lower academic rank and status, lack parity with tenure-track faculty, are often silenced in matters of institutional governance, and struggle to fit within the traditional university setting and norms (Ayala et al., 2018; Beaulieu, 2020; Wertheimer & Sodhi, 2014). Additionally, field offices are often woefully understaffed and underresourced, which furthers the perception that field directors are not as valued as their tenure-track counterparts (Lyter, 2012; Wertheimer & Sodhi, 2014).

To respond to these challenges, field directors gain significant support through the utilization of strong peer networks, collaborative arrangements with other schools of social work, and robust resource sharing through local and regional consortia (Bogo, 2015; Jarman-Rohde et al., 1997; Lager & Robbins, 2004). Overall, these resources help field directors manage the intensity of the work, which allows them to respond to student, departmental, institutional, and community needs (Lager & Robbins, 2004). There were significant changes made to practicum education during the pandemic, mostly centered on employment-based internships, supervision within these placements, and a reduction in hours. Some of these changes have continued. With the updated 2022 EPAS guidelines related to infusing ADEI more intentionally throughout the curriculum, and which extend to student internships, practicum education is rapidly evolving (CSWE, 2022). While CSWE has given programs great latitude to implement these changes, the lack of specific direction on how to operationalize them may result in inconsistent, or potentially ineffective, applications across social work programs.

There is emerging literature discussing the collective fatigue and sense of shared trauma as it relates to the pandemic (Bender et al., 2021; Haight et al., 2022; Sherwood et al., 2021; Stanley et al., 2021). Despite this growing body of research, there is a lack of literature specifically focusing on field directors (Au et al., 2023; DeFries et al., 2021). Field directors, social work education, and the broader academy will be wrestling for years to come with how to respond to workforce challenges, the need for quality supervision within internships, the student mental health crisis, and overall student experiences within higher education. Additionally, concerns regarding the toll these challenges will take on field directors and others connected to field education are areas to be explored.

The research on field directors as a population is scarce (Au et al., 2023; Beaulieu, 2020; Drolet et al., 2020). While several national, exploratory studies have been conducted to ascertain field directors’ perceptions of their value and overall satisfaction, the author has been unable to locate any recent studies which would consider the significant changes to the landscape of higher education due to the pandemic. Data from previous studies, and information participants shared during these interviews, seem to suggest that the pandemic may have exacerbated feelings of collective fatigue and being undervalued. Since there is a lack of research on this population overall, and even less on these specific areas, this warrants further exploration.

Implications for Social Work Education

The designation of field education as the signature pedagogy of social work education cannot be overstated and has been repeatedly reaffirmed and discussed within the literature. Field is hailed as the most important aspect of social work education, where theory, knowledge, and skills all are applied. If social work education is committed to this, it is critical that field directors are valued and supported within the academy. This begins with faculty and departmental leadership understanding the unique role field directors hold. It is crucial that those in leadership positions understand the multiple stakeholders served by field directors, as well as how their needs have shifted after the pandemic. These significant changes during and after the pandemic have been contributing factors to field directors expressing a sense of collective fatigue.

Further, field directors should be given roles of leadership in title and in practice. Field directors should be fully involved in departmental and institutional governance. Social work departments and the larger institutions must ensure the field office is adequately staffed, resourced, and supported. Institutions must ensure field directors are members in local and regional consortiums, where vital information and resources are exchanged and mentorship between field directors, and a sense of community, occurs. The position of the field director should be elevated within the academy and treated as equally important as that of a faculty member, and thereby receive the same rights, rank, compensation, and status. It is imperative that social work educators work to close the disparity many field directors encounter within the academy and advocate for these supports at all levels. Without these supports, the trends in field director turnover and lost connections within the communities that are served could continue, thus jeopardizing the signature pedagogy of social work education.

Strengths and Limitations

Field directors were able to share their experiences; however, varying degrees of stress, fatigue, personal and professional challenges, and other extenuating factors may have impacted what participants shared. As with any practice-close research, inherent strengths and potential limitations exist (Baumbusch, 2010; Lykkeslet & Gjengedal, 2007; Wyse et al., 2018). Being employed within higher education and serving in the role of field director allows the author to understand the structure and expectations of field. The author’s role lends credibility and a level of competence to the research, as well as provides an ability to engage in relationships with other field directors. However, challenges related to preconceived thoughts and potential practice experiences leading to a biased understanding of the stories shared were issues of which the researcher was mindful. Attending to these issues occurred through clearly defining the research questions and methodology, as well as the use of reflection and debriefing during the study (Lykkeslet & Gjengedal, 2007; Wyse et al., 2018). Additionally, asking participants to reflect on the totality of the pandemic could be challenging, as time has elapsed since the beginning of the pandemic, making it perhaps difficult to remember all the details.

This study adds to the existing body of literature, and its findings warrant further exploration to understand more deeply the pandemic’s impact on field directors’ experiences in general and on other areas of their role. There were a relatively limited number of responses (N = 16)despite two forms of sampling. Therefore, findings may not be representative of all field directors. Membership in several of the listservs where recruitment invitations were distributed is open to all faculty regardless of title. While many members do hold the title of field director, the exact number is unknown, thus the sample size is difficult to ascertain. As this study asked participants to self-report their experiences during the pandemic, potential participant bias or social desirability issues may be present (Morgado et al., 2018). Participants’ reports of their attitudes are representative of the sample size; however, results cannot be generalized to settings and populations beyond the responses obtained.

Future Research

As the impact of the pandemic is only beginning to be understood, it is critical to assess how field directors’ jobs have changed because of it, and to engage in candid conversations regarding how field directors are adapting to various stakeholder needs post-pandemic. There was an overall sense of collective fatigue and concern regarding the disconnection expressed by participants, which should be further studied. As this sense of fatigue has been noted in other pandemic-related research, understanding this from the field director’s perspective is important to mitigating burnout.

Assessing how field directors and practicum offices are connecting and overall garnering support is also an area ripe for future research. As reflected in the findings, the power of the field community is a significant source of support. Further assessment is warranted on ways programs can support this level of connection. Finally, as field directors are called to respond to institutional, community, and student challenges, it is incumbent on social workers within higher education to advocate for these resources and for equity within field education. Field directors play a vital role in designing, implementing, and evaluating the signature pedagogy of social work education. Therefore, institutions and the accrediting body should intentionally evaluate whether field directors are held in the same esteem as tenured and tenure-track faculty. Valuing those responsible for delivering the signature pedagogy of social work education calls for honest evaluation and tireless advocacy. Only when we truly value, treat, and compensate field directors equitably will we see a positive impact on retention, morale, and overall satisfaction.

References

Archer-Kuhn, B., Ayala, J., Hewson, J., & Letkemann, L. (2020). Canadian reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic in social work education: From tsunami to innovation. Social Work Education, 39(8), 1010–1018.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1826922

Au, C., Drolet, J. L., Kaushik, V., Charles, G., Franco, M., Henton, J., Hirning, M., McConnell, S., Nicholas, D., Nickerson, A., Ossais, J., Shenton, H., Sussman, T., Verdicchio, G., Walsh, C. A., & Wickman, J. (2023). Impact of COVID-19 on social work field education: Perspectives on Canadian social work students. Journal of Social Work, 23(3), 522–547.

https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173231162499

Ayala, J., Drolet, J., Fulton, A., Hewson, J., Letkemann, L., Baynton, M., Elliott, G., Judge-Stasiak, A., Blaug, C., Tétreault, A. G., & Schweizer, E. (2018). Restructuring social work field education in 21st century Canada. Canadian Social Work Review, 35(2), 45–65.

https://doi.org/10.7202/1058479ar

Baumbusch, J. (2010). Semi-structured interviewing in practice-close research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 15(3), 255–258.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2010.00243.x

Beaulieu, S. R. (2020). The training and mentoring of social work field directors within the academy: An ethical dilemma or not? [Doctoral dissertation, University of St. Thomas].

https://ir.stthomas.edu/ssw_docdiss/68

Bender, A. E., Berg, K. A., Miller, E. K., Evans, K. E., & Holmes, M. R. (2021). “Making sure we are all okay”: Healthcare workers’ strategies for emotional connectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Social Work Journal, 49, 445–455.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-020-00781-w

Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices for contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43, 317–324.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

Bonano-Broussard, D., Henry, A., Williams, N., Mitchell, D., & Savani, S. (2023). Social work field education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review of the literature. Field Educator, 13(1), 1–21.

https://tinyurl.com/mrxepya2

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 32(2), 77–101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

Bright, C. L. (2020). Social work in the age of a global pandemic. Social Work Research, 44(2), 83–86.

https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svaa006

Casacchia, M., Cifone, M. G., Giusti, L., Fabiani, L., Gatto, R., Lancia, L., Cinque, B., Petrucci, C., Giannoni, M., Ippoliti, R., Frattaroli, A. R., Macchiarelli, G., & Roncone, R. (2021). Distance education during COVID-19: An Italian survey on the university teachers’ perspectives and their emotional conditions. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02780-y

Cederbaum, J. A., Ross, A. M., Zerden, L., Estenson, L., Zelnick, J., & Ruth, B. J. (2022). “We are on the frontlines too”: A qualitative content analysis of US social workers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health and Social Care in the Community, 30, 5412–5422.

https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13963

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, May 5). End of the federal COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) declaration. https://tinyurl.com/y6hdffxt

Council on Social Work Education (2008). 2008 educational policy and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs. https://tinyurl.com/58xx58t2

Council on Social Work Education (2015). 2015 educational policy and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs.

https://tinyurl.com/bddpukxn

Council on Social Work Education (2022). 2022 educational policy and accreditation standards.

https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/policies-process/2022epas/

Davis, A., & Mirick, R. G. (2021). COVID-19 and social work field education: A descriptive study of students’ experiences. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), 120–136.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1929621

DeFries, S., Kates, J., Brower, J., & Wrenn, R. (2021). COVID-19: An existential crisis for social work field education. Field Educator, 11(1), 1–7. https://tinyurl.com/ac7duahk

Dempsey, A., Lanzieri, N., Luce, V., de Leon, C., Malhotra, J., & Heckman, A. (2022). Faculty response to COVID-19: Reflections-on-action in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50, 11–21.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00787-y

Drolet, J. L., Alemi, M. I., Bogo, M., Chilanga, E., Clark, N., St. George, S., Charles, G., Hanley, J., McConnell, S. M., McKee, E., Walsh, C. A., & Wulff, D. (2020). Transforming field education during COVID-19. Field Educator, 10(2), 1–9. https://tinyurl.com/2p9zd25t

Ellison, M. L., & Raskin, M. S. (2014). Mentoring field directors: A national exploratory study. Journal of Social Work Education, 50, 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.856231

Evans, E. J., Reed, S. C., Caler, K., & Nam, K. (2021). Social work students’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and themes of resilience. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(4), 771–783.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1957740

Fay, D., & Ghadimi, A. (2020). Collective bargaining during times of crisis: Recommendations from the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 815–819.

https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13233

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2020, March 14). Fact sheet: COVID-19 emergency declaration [Press Release]. https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20210318/COVID-19-emergency-declaration

Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

Fernandez, A. A., & Shaw, G. P. (2020). Academic leadership in a time of crisis: The coronavirus and COVID-19. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.21684

Filho, W. L., Wall, T., Rayman-Bacchus, L., Mifsud, M., Pritchard, D. J., Lovren, V. O., Farinha, C., Petrovic, D. S., & Balogun, A. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 and social isolation on academic staff and students at universities: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21, 1213–1232.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11040-z

Gates, T. G., Bennett, B., & Baines, D. (2023). Strengthening critical allyship in social work education: Opportunities in the context of #BlackLivesMatter and COVID-19. Social Work Education, 42(3), 371–387.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.1972961

Haight, W. L., Suleiman, J., Flanagan, S. K., Park, S., Soltani, L. JS., Carlson, W. C., Otis, J. R., & Turck, K. S. (2022). Reflections on social work education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of faculty members and lessons moving forward. Qualitative Social Work, 22(5), 938–955.

https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250221114390

Jarman-Rohde, L., McFall, J., Kolar, P., & Strom, G. (1997). The changing context of social work practice: Implications and recommendations for social work educators. Journal of Social Work Education, 33(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.1997.10778851

Keesler, J. M., Wilkerson, D., White, K., & Dickinson, S. (2022). Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on social work students: Burnout and resilience during a global pandemic. Advances in Social Work, 22(3), 1024–1045. https://doi.org/10.18060/26394

King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp.257–270). Sage.

Krishnamoorthy, R., & Keating, K. (2021). Education crisis, workforce preparedness, and COVID-19: Reflections and recommendations. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 80(1), 253–274.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12376

Lager, P. B., & Robbins, V. C. (2004). Guest editorial: Field education: Exploring the future, expanding the vision. Journal of Social Work Education, 40(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2004.10778475

Leitch, J., Grief, G. L., Saviet, M., & Somberday, D. (2021). Social work education at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic: Narrative reflections and pedagogical responses. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 41(5), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2021.1988031

Lykkeslet, E., & Gjengedal, E. (2007). Methodological problems associated with practice-close research. Qualitative Health Research, 17(5), 699–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307299216

Lyter, S. C. (2012). Potential of field education as signature pedagogy: The field director role. Journal of Social Work Education, 48(1), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2012.201000005

Mahmood, S. (2021). Instructional strategies for online teaching in COVID-19 pandemic. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.218

McLaughlin, H., Scholar, H., & Teater, B. (2020). Social work education in a global pandemic: Strategies, reflections, and challenges. Social Work Education, 39(8), 975–982.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1834545

Melero, H., Hernandez, M. Y., & Bagdasaryan, S. (2021). Field note—Social work field education in quarantine: Administrative lessons from the field during a worldwide pandemic. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1929623

Morgado, F. F. R., Meireles, J. F. F., Neves, C. M., Amaral, A. C. S., & Ferreira, M. E. C. (2018). Scale development: Ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crĭtica, 30(3). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0057-1

Morley, C., & Clark, J. (2020). From crisis to opportunity? Innovations in Australian social work field education during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Social Work Education, 39(8), 1048–1057.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1836145

Murray-Lichtman, A., Aldana, A., Izaksonas, E., Williams, T., Naseh, M., Deepak, A. C., & Rountree, M. A. (2022). Dual pandemics awaken urgent call to advance anti-racism education in social work: Pedagogical illustrations. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 31(3-5), 139–150.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2022.2070899

Nowell, L., Norris, J., White, D., & Moules, N. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1609406917733847

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

Padgett, D. (2017). Qualitative methods in social work research. Sage Publications, Inc.

Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. (2016). Research methods for social work. Thompson Brooks/Cole.

Sherwood, D., VanDeusen, K., Weller, B., & Gladden, J. (2021). Teaching note—Teaching trauma content online during COVID-19: A trauma-informed and culturally responsive pedagogy. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(sup1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1916665

Stanley, B. L., Zanin, A. C., Avalos, B. L., Tracy, S. J., & Town, S. (2021). Collective emotion during collective trauma: A metaphor analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative Health Research, 31(10), 1890–1903.

https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211011589

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020, January 31). Determination that a public health emergency exists. https://aspr.hhs.gov/legal/PHE/Pages/2019-nCoV.aspx

VanLeeuwen, C. A., Veletsianos, G., Johnson, N., & Belikov, O. (2021). Never-ending repetitiveness, sadness, loss, and “juggling with a blindfold on:” Lived experiences of Canadian college and university faculty members during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1306–1322. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13065

Wertheimer, M. R., & Sodhi, M. (2014). Beyond field education: Leadership of field directors. Journal of Social Work Education, 50(1), 48–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.856230

Wyse, D., Brown, C., Oliver, S., & Poblete, X. (2018). The BERA close-to-practice research project: Research Report. British Educational Research Association. https://www.bera.ac.uk/project/close-to-practice-research-project