Abstract

In order to be competent social workers, it is necessary for social work students to understand who they are and how their experiences shape their perceptions of the world. Exploring how one’s unique identity characteristics influence or limit access to systems of power and privilege is the essence of intersectionality. This exploratory, qualitative study aimed to examine the degree to which intersectionality was infused into MSW field syllabi. The implications of the findings suggest that intersectionality is not fully integrated into MSW field syllabi. Results of this study summarize opportunities within social work education to increase students’ awareness of intersectionality.

Keywords: intersectionality; MSW field education; syllabi; social location; EPAS

Understanding who we are as individuals and how our social identities shape our lived experiences and impact our practice is a difficult but necessary exploration for social workers. Social workers can examine themselves and their experiences by using an intersectional lens or framework. Intersectionality is defined as how a person’s unique social location or identities, which include gender, race, sexuality, ethnicity, social class, culture, and other identifying characteristics, converge and are impacted by power, oppression, and discrimination (Hankivsky, 2014; Simon et al., 2021). Social work students need to recognize that their social locations can situate them in both the positions of the oppressor and the oppressed (Bubar et al., 2016). Therefore, as social work educators, we must challenge students to examine themselves through an intersectional lens.

Beginning in 2008, with further refining in 2015, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE, 2015), through their Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS), outlined that intersectionality must be included as an element of education and practice assessment (Alvarez-Hernandez, 2020; Bubar et al., 2016; Simon et al., 2021). Recent social work research highlights the importance of intersectionality for social work education; however, the dearth of research related to where and how social work programs are infusing intersectionality into classrooms suggests that this theory may not be being viewed as a priority (Bubar et al., 2016; Jani et al., 2011; Simon et al., 2021).

Simon et al. (2021) contended that social work professionals must be in a position to work with individuals whose intersecting social identities are intensified by various oppressive systems. In order to prevent a disconnect in their practice, social workers need to have a clear awareness of their own intersecting identity characteristics, and this personal and professional awareness must initially be developed within the classroom (Craig et al., 2017). Social work education programs are in a position to provide a safe environment that allows students to examine and reconcile their unique social location and intersecting identity traits, so they are able to develop an awareness of how power and oppression influence their experiences and of the power disparities that many clients navigate (Alvarez-Hernandez, 2020).

Given the limited guidance from CSWE regarding how intersectionality should be incorporated into programs and courses, a qualitative research study was conducted that examined Master’s of Social Work (MSW) field education and field seminar syllabi. The central research questions were: Are MSW programs integrating intersectionality into field education and seminar courses? and What methods are social work instructors using to infuse intersectionality into field education and field seminar courses? This paper examines the results of this study, addresses if and how a sample of programs infuse intersectionality into courses, and explores the extent to which they meet the standards outlined in the EPAS.

Literature Review

Race, class, and gender influence how we view the world and how others view us. However, there is more to each of us than race, class, and gender. Intersectionality is a theory that allows us to examine how these three identity characteristics, along with many others including sexuality, age, and gender identity, weave together and impact our experiences and worldview. In order to fully see ourselves through an intersectional perspective, it is necessary to recognize how our diverse and unique identities afford us moments of privilege, power, and resources, and also can bring oppression and discrimination (Robinson et al., 2016). Across disciplines, researchers acknowledge that employing an intersectional perspective can help us understand how our social identities are influenced or limited by power (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016).

Intersectionality

Intersectionality, initially introduced as a legal theory by Kimberlé Crenshaw over 30 years ago, impacts many legal, social, and health disciplines (Carbado & Harris, 2019; Cho et al., 2013; Collins, 2015; Moradi et al., 2020). Moving beyond its initial application within the legal field, intersectionality has evolved into a buzzword, leading to concerns from scholars that it is losing the fidelity of the original ideologies of the theory (Collins, 2015; Moradi et al., 2020; Nash, 2017). Researchers agree that intersectionality is rooted in early feminist theories dating back to as early as the 1850s, when Sojourner Truth questioned such crossroads, and, more recently, to the Combahee River Collective (Bubar et al., 2016; Harris & Patton, 2019; Jani et al., 2011; Moradi et al., 2020). The literature highlights that feminists of color have questioned conventional philosophies and the effects of intersections of race, gender, and class on the access or limits to systems of power and privilege (Cole, 2009).

Intersectionality, often referred to as a multilayered paradigm (Marfelt, 2016), requires an individual to explore their unique coordinating social characteristics and how those characteristics impact their identity and views of the world (Jani et al., 2011). A further, advanced definition of the theory articulates that a person’s experiences, whether of power and privilege or of oppression and inequities, are the culmination at the crossroads of their unique social identities, and not the consequence of individual factors (Hankivsky, 2014).

Intersectionality recognizes how power shapes identities and how those identities shape, influence, and/or limit power. As individuals assess their identity coordinates, it is critical to acknowledge that they can exist at the junction of oppression and privilege (Hankivsky, 2014; Marfelt, 2016; Mehrotra, 2010; Rosenthal, 2016). The definition and use of intersectionality across multiple disciplines has shifted from its early roots of examining the crossroads of gender and race within oppressive systems. Research maintains that it is necessary, when defining and implementing an intersectional approach, to include how oppressive systems and oppression can impact individuals based on their unique identity characteristics (Marfelt, 2016).

Intersectionality and Higher Education

Throughout the last two decades, intersectionality has been studied and integrated within several disciplines, including medicine, psychology, sociology, social sciences, law, and many other professions (Harris & Patton, 2019; Rosenthal, 2016). Historically, concepts of intersectionality date back to the 1850s; however, within the academy, integration of these concepts is still in its early stages (Murphy et al., 2009). The literature reflects that intersectionality entered the academic world through women’s and feminist studies that introduced various analyses on race, gender, sexuality, and class (Collins, 2015; Moradi et al., 2020). Although complex and challenging to infuse, college classrooms across various disciplines now focus on an intersectional approach (Rosenthal, 2016). Social identities are multifaceted and unique, and using intersectionality in higher education allows students to begin to understand the magnitude of these crossroads (Lerner & Fulambarker, 2018). Intersectionality, when purposefully included in higher education, can “transform knowledge, transform society, and transform higher education” (Harris & Patton, 2019, p. 349).

There is debate regarding how to classify intersectionality; many question whether it is a theory, a concept, or a term, which influences its inclusion in higher education (Harris & Patton, 2019; Murphy et al., 2009). Intersectionality as a theory allows us to acknowledge how our multifaceted social identities impact moments of oppression and privilege (Bubar et al., 2016). When viewing intersectionality as a complex term, it can be considered as a form of both “critical inquiry” and “critical praxis” (Nash, 2017). In addition to the debate over classifying intersectionality, there is a dispute regarding who can use the theory in practice and how intersectionality is applied across disciplines (Harris & Patton, 2019). The literature that examines intersectionality in the academy reminds us of the importance of moving beyond the debate about defining the term, and focusing instead on how intersectionality can impact higher education and the promotion of advancing social justice (Harris & Patton, 2019; Rosenthal, 2016).

Intersectionality and Social Location

An individual’s ability to access resources within systems of power is impacted by their social location and unique identities (Kendall & Wijeyesinghe, 2017). Awareness of one’s social location, which is defined as the different groups with whom a person identifies based on their unique experiences, gender, class, ethnicity, positions within society, and culture, can impact one’s intersectional lens (Bubar et al., 2016). Understanding one’s social location requires a person to look beyond their individual identity characteristics of gender, race, and class to examine how these characteristics intertwine simultaneously (Murphy et al., 2009).

Working from an intersectional framework or perspective affords a person the context to understand their social location and the interconnectedness that exists (Garcia, 2016; Murphy et al., 2009; Windsong, 2018). Further research articulates that when individuals examine their social location through an intersectional lens, the relationship between the institutional systems that control or limit privilege and their social identity is magnified (Kendall & Wijeyesinghe, 2017). An individual’s lived experiences are impacted by their social location. When students are taught about intersectionality, they can connect the relationship between their multiple identity characteristics and social locations and how they adjust, survive, and thrive (Craig et al., 2021).

Intersectionality and Social Justice

Across academic disciplines, students are learning about the importance of social justice work (Kendall & Wijeyesinghe, 2017; Mehrotra et al., 2019). Focusing on intersectionality is one way to orient students to the importance of social justice work in different disciplines (Hankivsky, 2014; Rosenthal, 2016). Research contends that intersectionality in the classroom is a way to promote social justice principles (Garcia, 2016; Lerner & Fulambarker, 2018). Social justice work is difficult, but examining privilege (or its lack) through an intersectional lens, and connecting how it is impacted and influenced by a person’s social location, is a necessary component of such work (Kendall & Wijeyesinghe, 2017).

Intersectionality and Social Work Education

Intersectionality is a critical approach for social work education and practice (Mehrotra et al., 2019; Murphy et al., 2009). Thirty years after intersectionality was introducedto the academy, the theory is now a part of the CSWE EPAS’s implicit curriculum and competencies. Initially reflected in CSWE’s 2008 EPAS, intersectionality remains included in the 2015 EPAS, in “Competency 2: Engaging Diversity and Difference in Practice and Education Policy, 3.0–Diversity” (Alvarez-Hernandez, 2020; CSWE, 2015; Simon et al., 2021). CSWE further defines intersectionality as “a paradigm for understanding social identities and the ways in which the breadth of the human experiences are shaped by social structures” (CSWE, 2015, p. 21).

Although CSWE provides a clear definition, schools of social work vary on how they define and teach intersectionality (Bubar et al., 2016; Murphy et al., 2009). Further, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) in 2009 also responded to the need to address intersectionality in social work education, research, practice, and policy, when they offered specific guidance on the value of intersectionality for the social work profession, and provided examples for how professionals can practice with an intersectional lens (Murphy et al., 2009; Simon et al., 2021).

Intersectionality is important for students to learn about, as it is a way to reconcile their unique and often complex identities and their overlap within various oppressive systems. The literature indicates that social work educators must employ an intersectional lens in their teaching to highlight the complex power dynamics that can exist between a social worker and their clients (Mehrotra et al., 2019). It is necessary to prepare future social workers to develop an intersectional approach to address the uniqueness of the clients and the systems with which they will be working (Murphy et al., 2009). While the literature highlights the importance of intersectionality for social work education and practice, incorporating it into the classroom remains a challenge, as the complicated ideas evoke intense emotion (Simon et al., 2021). Social work educators must create safe learning spaces in which students can have honest discussions regarding their intersectional identities.

Instructors of social work courses face challenges associated with the limited guidance regarding where and how to include intersectionality (Bubar et al., 2016; Jani et al., 2011). Yet research reflects that when intersectionality is incorporated into social work courses, students’ knowledge base and future work are positively impacted (Bubar et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2016). Incorporating intersectionality into courses will promote the development of the necessary skills and values needed to practice as future social workers (Murphy et al., 2009). A primary goal of intersectionality was to promote equity and social justice, which aligns with the social work profession; therefore, intentionally infusing intersectionality into social work courses will ultimately benefit our profession and society (Rosenthal, 2016).

Methodology

Design

Syllabi are powerful tools for instructors, and provide a roadmap for what a student is expected to learn in any specific course. This study used qualitative methods to discover if and how social work instructors are infusing intersectionality into MSW field education and field seminar syllabi. The literature reflects that analyzing syllabi is a seldom-pursued research activity in social work education; however, there is a wealth of information available through such analysis that can contribute to social work curriculum development (Mehrotra et al., 2017). Examining syllabi provides insight into how programs and their courses meet the CSWE requirement to include intersectionality in the social work curriculum.

Data Collection

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval to conduct this study was obtained. This qualitative study sought to collect MSW field education and field seminar syllabi from CSWE-accredited programs. Recruitment emails were sent to various social work listservs, including the Association of Baccalaureate Program Directors (BPD) listserv, the MSW listserv, and CSWE’s Field Director listserv. Details of the study were clearly articulated in the email. It was explained to potential participants that the goal of this voluntary study, with minimal risk to participants, was to learn if and how intersectionality is included in field education and field seminar syllabi.

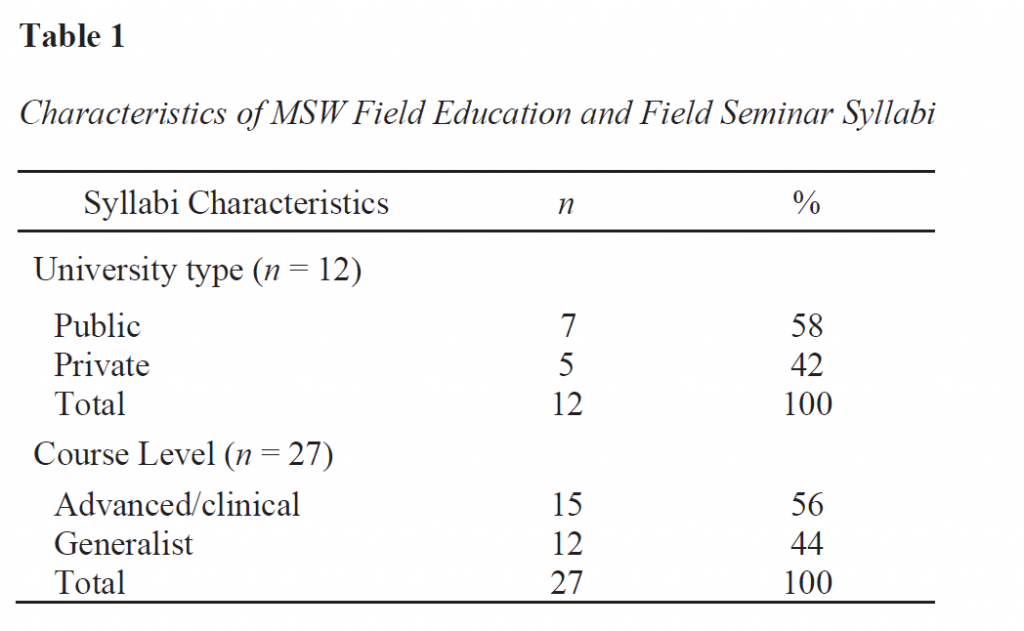

The primary inclusion factor for this study was that syllabi must be from both a CSWE-accredited MSW program and for field education and/or field seminar courses. The method of teaching (i.e., online versus face-to-face) was not an exclusion factor. After three email attempts to the listservs, a total of 27 syllabi from 12 different universities was collected. Private and public universities were represented, with 58% of respondents from public universities and 42% from private universities. These percentages mirror CSWE’s MSW program statistics, with recent data highlighting that programs are 57% public universities and 43% private universities (CSWE, 2019). The syllabi collected included both generalist year (n = 12) and concentration or clinical year (n = 15) syllabi. Six submitted syllabi had to be excluded as they did not match the criteria requirements. These included courses from a BSW program, a course about intersectionality, a Human Behavior in the Social Environment course, a policy course, and an elective course.

Data Analysis

The 27 syllabi were uploaded and coded in NVivo 1.5.1(940), a qualitative data analysis software system. Grounded theory guided the analysis of the syllabi to uncover patterns in the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Initial data analysis started with open coding of the syllabi, using an inductive approach (Padgett, 2017). After the initial coding, a content analysis approach allowed the development of further codes and themes after interpreting the textual data (Mehrotra et al., 2017). Using a content analysis approach with syllabi allowed the identification of specific words within the text and further inferences about the syllabi (Sweifach, 2014). Initial codes and themes were developed and further refined.

During the first phase of open coding, the term intersectionality was searched for in all syllabi. Additional words associated with intersectionality, such as social location, social justice, identities, oppression, and power, were also queried. The second phase of content analysis of the syllabi focused specifically on assignments, readings, and course objectives. Codes were sorted into categories and subcategories, and three themes evolved.

Issues of trustworthiness and rigor were addressed in several distinct ways. Threats to trustworthiness are primarily researcher bias. Researcher bias happens when the researcher’s personal opinions or preconceived notions interfere with the research process or interpretation of the data (Padgett, 2017). There were a number of ways I worked to reduce researcher bias. Regular debriefings were held, as such practice can positively reduce threats to trustworthiness by protecting the researcher from their own bias while also offering additional insight (Padgett, 2017).

One final way trustworthiness and rigor was addressed was through the use of reflexivity throughout the research process, data collection, and data analysis, in order to ensure that I did not unduly influence the participants, the data, or the results (Probst, 2015). Reflexivity occurs when the researcher regularly reflects on their assumptions, biases, and experiences and how they influence the research process and results (Rubin & Babbie, 2017). Intersectionality is a theory that requires critical reflection, and this level of reflexivity was necessary throughout the study process (Probst, 2015).

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the fact that 27 different MSW field education and field seminar syllabi were received and analyzed. Both public and private universities submitted syllabi, and the representation was similar to recent CSWE data on MSW programs across the country. According to CSWE’s recent statistics on social work education, 57% of MSW programs are at public universities, while 43% are housed within private universities (CSWE, 2019). Fifty-eight percent of the syllabi analyzed in this study were from programs at public universities, and 42% were from private universities. Another strength of this study was the decision to review field education and field seminar syllabi. Fieldwork can be the first time students have the opportunity to practice their work through an intersectional lens. Syllabi often reflect course priorities, and if the inclusion of intersectionality was viewed as a course priority, it would be reflected in the content of the syllabus.

Several limitations must be acknowledged with this qualitative study. The first is that the overall number of syllabi analyzed is a small representation of the number of accredited MSW programs. Attempts were made to collect data through various social work education listservs; however, not all faculty are members of these listservs. According to recent CSWE statistics, there are 272 MSW programs (CSWE, 2019), and this study only captured a small representation of programs. However, the percentages of syllabi collected closely represented CSWE’s statistics of MSW programs in public versus private universities.

Further, it is also recognized that the information taught, and the manner in which an instructor teaches, is not limited to the information listed in the syllabi. For example, many syllabi listed that materials and readings would be posted in the course’s online learning management system. Mehrotra et al. (2017) postulated that a syllabus represents only one aspect of a course and does not necessarily offer a complete interpretation of what may be occurring in the classroom. Instructors may include, disseminate information about, and discuss intersectionality in the classroom, even if it is not listed in the syllabus.

Findings

After three separate attempts to collect syllabi from various listservs, 27 syllabi that met the criteria to be evaluated were received. Table 1 highlights the characteristics of the syllabi, including the type of university and the course levels the syllabi represented.

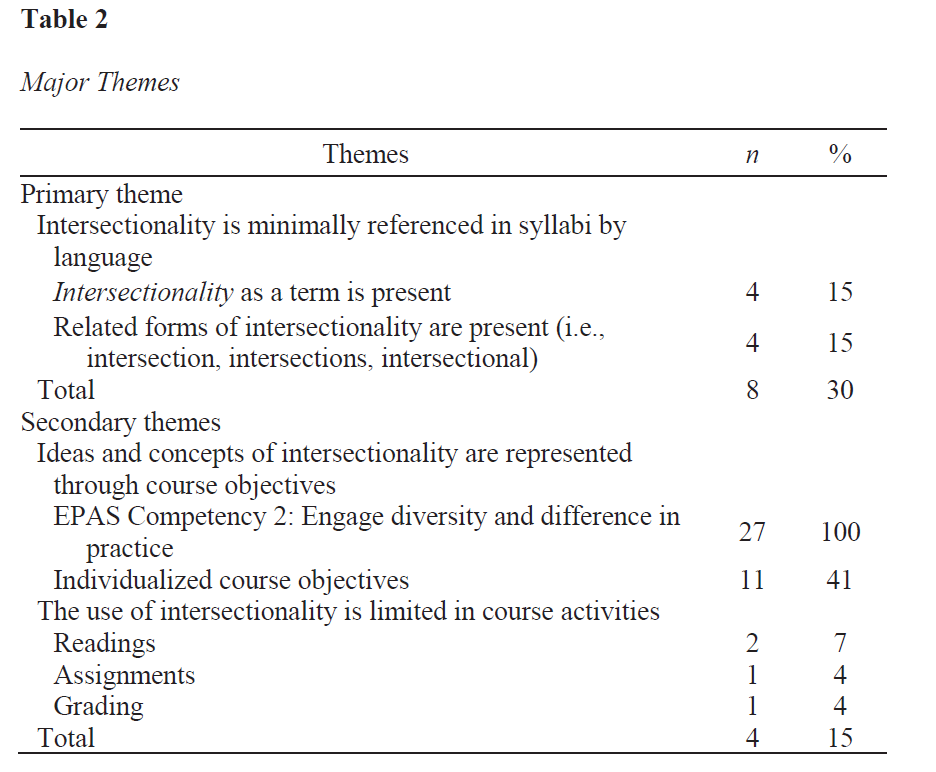

Syllabi were reviewed to determine if MSW programs integrated intersectionality into field education and/or field seminar classes. After completing the analysis, a primary theme and two secondary themes emerged. The primary theme, Intersectionality is minimally referenced in syllabi by language, and secondary themes, Ideas and concepts of intersectionality are represented through course objectives, and The use of intersectionality is limited in course activities, are reported in Table 2.

Primary Theme

Results of a content analysis of the field education and field seminar syllabi found that the word intersectionality is minimally referenced directly in syllabi. This emerged as the primary overarching theme of this analysis. Only four syllabi, or 15%, explicitly included the word. Intersectionality was referenced in one syllabus within the title of assigned reading material, and two syllabi included intersectionality in defining overall course objectives. Finally, one syllabus used the term intersectionality within an assignment reflection question by asking students to consider the key elements of intersectionality.

When broadening the search to include derivatives of intersectionality, such as intersection, intersections, and intersectional, four additional syllabi, or another 15%, were identified. All four of these syllabi used the words to define course objectives and/or learning objectives. Overall, 30%, or only eight of 27 syllabi, referenced some form of the word.

Secondary Themes

Ideas and Concepts of Intersectionality are Represented Through Course Objectives

The ideas and concepts of intersectionality are inherent in the overall social work profession. Intersections of race, gender, and class impact an individual’s access to systems of power and privilege. Social workers must have an awareness of how these overlapping identities also perpetuate oppressive systems. Examination of the 27 syllabi revealed that all of the syllabi did specifically reference the EPAS’s “Competency 2: Engage Diversity and Difference in Practice” in the course outline and/or learning objectives. Within social work education, specifically CSWE’s EPAS, the components of intersectionality are explicitly incorporated in Competency 2 (CSWE, 2015).

Intersectionality as an idea is embedded in the EPAS’s Competency 2; however, when looking specifically at unique course objectives or learning outcomes, the infusion of intersectionality is reduced. In examining the syllabi’s course objectives or learning outcomes separate from the EPAS, the incorporation of intersectionality drops to only 41%, or 11 out of 27 syllabi. One example of the infusion of intersectionality is illustrated by an instructor expanding on CSWE’s definition of Competency 2 in the following example: “Recognize and articulate that identity experiences are affected by intersections of social identity (i.e., age, class, gender, sexual orientation, religion, race, culture, ethnicity, immigration status, tribal sovereignty) that produce different realities for all people.” Another instructor included intersectionality in “Competency 3: Advance Human Rights and Social, Economic, and Environmental Justice” as a course-level objective by stating, “Understand and apply the intersectional knowledge between human rights frameworks and the principles of trauma-informed care with individual, families, communities, and the workforce across micro, mezzo, and macro practice.” These examples reflect various ways that the ideas of intersectionality are grounded in the EPAS and course objectives or learning outcomes.

Additional course objectives not explicitly linked to the EPAS competencies further accentuated ways instructors infused the ideas and concepts of intersectionality into syllabi. The following examples illustrate how instructors infused intersectionality into course objectives without overtly using the term: “Understand the forms and mechanisms of oppression, privilege, and discrimination and the strategies of change that advance social and economic justice”; “Advocate for societal change that breaks down structures of power and privilege that oppress, alienate, or exclude marginalized populations”; and “Recognize and articulate the power differentials based in social identity that may affect the clinical relationship.” Additional examples of course objectives that included ideas of intersectionality included keywords such as oppression, advancing social justice, and diversity.

The Use of Intersectionality is Limited in Course Activities

Limited infusion of intersectionality into field education and field seminar course activities was identified as the final theme. As listed in Table 2, only four syllabi, or 15%, had somehow integrated intersectionality into course activities such as assigned readings, assignments, or grading criteria. Two out of 27 syllabi (7%) introduced students to critical authors on intersectionality. In one course, students were required to readKimberlé Crenshaw’s 1989 manuscript “Demarginalizing the Intersections of Race and Gender: A Black Feminist’s Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” and a second course’s reading list included Patricia Collins’s 2015 article “Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemma.” Only one syllabus clearly included intersectionality in an assignment, as exemplified by the following question, which students had to assess as a part of a larger assignment: “Consider the key elements of intersectionality as you consider how different dimensions of your identity can be associated with different levels of power and privilege.” Finally, one instructor highlighted grading procedures that referenced values of intersectionality through the following criteria: “Raises relevant questions and awareness of multiple perspectives.”

Participant Comments

Various instructors who supplied syllabi also provided comments regarding the scope of the research and their opinions on whether their syllabi included intersectionality. The following comments evidence participants’ awareness of intersectionality, even if syllabi referenced the theory only minimally. Responses included, “Doubtful you will see intersectionality clearly articulated in our field program syllabi so looking forward to your findings and recommendations” and “Our syllabi we keep general and the majority of the content and assignment descriptions are in the course (Canvas) so I am not sure how helpful our syllabi are going to be.” Participants also provided information regarding various ways their programs infuse intersectionality throughout courses, as highlighted in the following statements: “Our school uses a model focused on human rights advocacy and social justice so most of our classes have a focus on intersectionality.” Finally, one participant commented on their interest in intersectionality in social work education: “Hoping to finalize an actual article coming out of student work on intersectionality.”

Discussion

Intersectionality in social work education and practice has moved beyond being just a buzzword. CSWE recognized the importance and value of intersectionality when it was added to the EPAS, first in 2008 and then again in 2015 (Bubar et al., 2016; CSWE, 2015). Intersectionality is essential to social work practice and research and has evolved as a critical lens (Mehrotra et al., 2019). This qualitative study examined 27 MSW field education and field seminar syllabi to uncover whether intersectionality was infused into the content of syllabi. The primary theme revealed in the results was that few of the examined MSW field education and field seminar syllabi incorporated intersectionality explicitly by language. Two secondary themes emerged, which identified ways syllabi included concepts of intersectionality in unique course objectives and learning outcomes, and showed how intersectionality was included in course activities such as assigned readings and reflection questions. The overall results bring attention to the fact that MSW field education and field seminar syllabi have significant room for improvement in incorporating intersectionality into the content.

These themes reflect similar findings in other studies. For example, Robinson et al. (2015) asserted that an intersectional framework would benefit students’ professional development; however, few programs infuse this theory into courses. Additional research highlighted comparable results by indicating that social work programs vary regarding defining and operationalizing intersectionality (Bubar et al., 2016), which may impact how the idea is included in syllabi. Teasley and Archuleta (2015) reflected on parallel themes when they discussed how the content of social justice and diversity issues in social work courses vary, and maintained that CSWE needs to provide further guidance on what they expect from programs.

Teaching intersectionality is challenging, as the ideas are personal and can invoke intense feelings. It can be difficult in the classroom for an instructor to feel comfortable navigating these emotionally charged discussions (Simon et al., 2021). Instructors must be willing and open to commence difficult conversations in the classroom that promote self-reflection (Craig et al., 2021). Although the ideas and values of intersectionality are embedded in Competency 2, how programs expand on teaching the competency is not always clear. All 27 syllabi did include and reference this competency. However, only 11 syllabi outlined the course and/or unique learning objectives in ways that included intersectionality or related terms and concepts. Previous research highlights that when intersectionality is embedded in the curriculum and defined in course objectives, it provides a foundation of learning for all students, especially marginalized students (Mehrotra et al., 2019). Without guidance and direction from CSWE regarding how these concepts should be taught and the necessary conversations that must follow, intersectionality is more likely to remain absent from courses, including field education and field seminar syllabi.

Implications and Future Opportunities

These findings suggest that educators teaching MSW field education and field seminar classes are not integrating intersectionality by explicit reference to this topic in their respective syllabi, and that there is significant room for improvement in teaching intersectionality. Though it can be challenging for social work educators to infuse intersectionality into the classroom (Craig et al., 2021), as educators we must remain intentional when evaluating our syllabi for the inclusion of this foundational theory. The inclusion of intersectionality can also be viewed as an ethical obligation. When it is included, it can demonstrate programs’ commitment to understanding diversity and difference and the complex world in which we live and work (Nash, 2017).

Working with students to develop themselves and their practice through an intersectional lens will increase students’ awareness of this critical theory. The combination of classroom and field placement is an ideal setting for this to occur. Integrating intersectionality in multiple units in both generalist and advanced field seminar classes is one suggestion. Students could be assigned to watch several videos and read multiple articles related to intersectionality. Discussions could be facilitated to encourage students to explore their social location and intersecting identities, so they can reconcile some of the disconnects or judgments they have made previously while in a safe classroom environment. Students might be required to critically reflect on their lived experiences, and further analyze how this positions them differently than their clients. Infusing assignments, critical reflection activities, and active learning into a classroom free of judgement allows for optimal growth and learning (Robinson et al., 2016).

Following the call for social work programs to institute standards for diversity development (Teasley & Archuleta, 2015), there should also be standards for the implementation and infusion of intersectionality in courses. Teasley and Archuleta (2015) emphasized similar themes when discussing how students in social work courses learn about social justice and diversity. They claimed that when there is no guidance for curricula on how to integrate these essential concepts, it becomes difficult to assess how students learn and apply the material. One example that CSWE could explore is to create a guidebook on how to integrate intersectionality across the competencies, similar to the guide they created for trauma-informed care.

Social work’s core values, including social justice, are similar to goals of intersectionality. Teaching intersectionality is not just another theory on identity, but is a theory that helps us understand how our lenses have been influenced and defined. It is necessary for social work programs to intentionally include this theory in order to allow our students a safe place in the classroom to begin to reconcile how their intersecting identities impact their lens and views of the world. Furthermore, students must also acknowledge that there may be instances when practicing as a social worker in which they may be in a position of both the oppressor and the oppressed. It is essential for future social workers to learn the practice skills, knowledge, and values necessary to work with cultural humility across diverse, intersecting identities and social locations (Azzopardi, 2020). These ideas are inherently difficult to balance, and these discussions must occur first within the classroom.

Additional research could also study what intersectionality means to social work educators, examining whether they have done their own work to unpack their intersecting coordinates and social location, and how this impacts their teaching and comfort with discussing an emotionally charged subject. It is recognized that it is difficult to teach these ideas, especially when, as a profession, we are not clear what intersectionality means or how to interpret it (Craig et al., 2021), so it may be helpful to explore further how social work instructors define, assess, and integrate intersectionality. Finally, as researchers have explored how and where social work programs have infused diversity content, future studies could expand on how programs are integrating intersectionality across the curriculum, not only in field education and seminar courses.

Conclusion

Intersectionality has traveled a journey from 19th century feminist theory to inclusion in present-day social work educational competencies. The ideology and principles of intersectionality mirror the mission and values of the social work profession. This theory has the power to bring perspective to the unique experiences that impact the lens through which we view the world around us. Intersectionality is something that our social work students need to be challenged to evaluate. As instructors, we must also be willing to examine who we are and how our experiences shape our practice. Though there is debate about who this theory “belongs to” and who can practice it, until we are all able to accept this theory, we will not be inclusive of it in our teachings and practice (Harris & Patton, 2019). Intersectionality brings attention to how our identity characteristics impact or limit our access to systems of power and privilege or bring us oppression. As social workers, it is imperative to understand our intersecting identities, as there may be instances when we are at the crossroads of being an oppressor and oppressed.

References

Alvarez-Hernandez, L. (2020). Teaching intersectionality across the social work curriculum using the intersectionality analysis cluster. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(1), 181–188. https://doi.org/fvq7

Azzopardi, C. (2020). Cross-cultural social work: A critical approach to teaching and learning to work effectively across intersectional identities. The British Journal of Social Work, 50(2), 464–482. https://doi.org/g2gb

Braun, B., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/fswdcx

Bubar, R., Cespedes, K., & Bundy-Fazioli, K. (2016). Intersectionality and social work: Omissions of race, class, and sexuality in graduate school education. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/ghx925

Carbado, D., & Harris, C. (2019). Intersectionality at 30: Mapping the margins of anti-essentialism, intersectionality, and dominance theory. Harvard Law Review, 132(8), 2193–2239.

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs, 38(4), 785–810. https://doi.org/gd228h

Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. The American Psychologist, 64(3), 170–180. https://doi.org/d3k8w7

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/gcx4rk

Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). (2015). Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards.

https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/standards/2015-epas/

Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). (2019). 2019 Annual Statistics on Social Work Education in the United States.

https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/215ee172-3f6e-464a-b435-7dd795f80129/cswe_rpt_19-m.pdf/

Craig, S. L., Gardiner, T., Eaton, A. D., Pang, N., & Kourgiantakis, T. (2021). Practicing alliance: An experiential model of teaching diversity and inclusion for social work practice and education. Social Work Education, 41(5), 1–19. https://doi.org/gwdq

Craig, S. L., Iacono, G., Paceley, M., Dentato, M., & Boyle, K. (2017). Intersecting sexual, gender, and professional identities among social work students: The importance of identity integration. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(3), 466–479. https://doi.org/ggmtc7

Else-Quest, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2016). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: I. Theoretical and epistemological issues. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/f8qmmf

Garcia, L. (2016). Intersectionality. Kalfou, 3(1), 102–106. https://doi.org/10.15367/kf.v3i1.90

Hankivsky, O. (2014). Intersectionality 101. The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy. https://tinyurl.com/i2q5ipfs

Harris, J. C., & Patton, L. D. (2019). Un/Doing intersectionality through higher education research. The Journal of Higher Education, 90(3), 347–372. https://doi.org/ghbdnt

Jani, J. S., Pierce, D., Ortiz, L., & Sowbel, L. (2011). Access to intersectionality, content to competence: Deconstructing social work education diversity standards. Journal of Social Work Education, 47(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/fw5nz9

Kendall, F. E., & Wijeyesinghe, C. L. (2017). Advancing social justice work at the intersections of multiple privileged identities. New Directions for Student Services, 2017(157), 91–100. https://doi.org/fvrc

Lerner, J. E., & Fulambarker, A. (2018). Beyond diversity and inclusion: Creating a social justice agenda in the classroom. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 38(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/fxjr

Marfelt, M. M. (2016). Grounded intersectionality. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 35(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/gh2hjq

Mehrotra, G. (2010). Toward a continuum of intersectionality theorizing for feminist social work scholarship. Affilia, 25(4), 417–430. https://doi.org/fcpx8w

Mehrotra, G. R., Hudson, K. D., & Self, J. M. (2017). What are we teaching in diversity and social justice courses? A qualitative content analysis of MSW syllabi. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 37(3), 218–233. https://doi.org/ghx92s

Mehrotra, G. R., Hudson, K. D., & Self, J. M. (2019). A critical examination of key assumptions underlying diversity and social justice courses in social work. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 30(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/gvrs

Moradi, B., Parent, M. C., Weis, A. S., Ouch, S., & Broad, K. L. (2020). Mapping the travels of intersectionality scholarship: A citation network analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/ggrjzm

Murphy, Y., Hunt, V., Zajicek, A. M., Norris, A. N., & Hamilton, L. (2009). Incorporating intersectionality in social work practice, research, policy, and education. NASW Press.

Nash, J. C. (2017). Intersectionality and its discontents. American Quarterly, 69(1), 117–129. https://doi.org/gfzgzk

Padgett, D. (2017). Qualitative methods in social work research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Probst, B. (2015). The eye regards itself: Benefits and challenges of reflexivity in qualitative social work research. Social Work Research, 39(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/f6496k

Robinson, M., Cross-Denny, B., Lee, K., Werkmeister Rozas, L., & Yamada, A. (2016). Teaching note—Teaching intersectionality: Transforming cultural competence content in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(4), 509–517. https://doi.org/ghtkxm

Rosenthal, L. (2016). Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: An opportunity to promote social justice and equity. The American Psychologist, 71(6), 474–485. https://doi.org/f844n8

Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. (2017). Research methods for social work. Cengage Learning.

Simon, J. D., Boyd, R., & Subica, A. M. (2021). Refocusing intersectionality in social work education: Creating a brave space to discuss oppression and privilege. Journal of Social Work Education, 58(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/gvjc

Sweifach, J. (2014). Group work education today: A content analysis of MSW group work course syllabi. Social Work with Groups, 37(1), 8–22. https://doi.org/gxc5

Teasley, M., & Archuleta, A. J. (2015). A review of social justice and diversity content in diversity course syllabi. Social Work Education, 34(6), 607–622. https://doi.org/ghx92t

Windsong, E. A. (2018). Incorporating intersectionality into research design: An example using qualitative interviews. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/gfv7p7