Abstract

This mixed-methods study examined field instructors’ (N = 58) perspectives on how to prepare social work students for mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) examined differences in field instructors’ perspectives of their educational roles and responsibilities by program level. Overall, field instructors strongly agreed that schools need to prepare students regarding their role as mandatory reporters (M = 1.61, SD = 0.78), and moderately agreed that schools do a good job in this endeavor (M = 2.57, SD = 0.95). Field instructors thought Master of Social Work (MSW) students had better awareness of mandatory reporting at the start of practicum [(F(2, 41) = 2.95, p = 0.06] compared to Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) or a mixed cohort of BSW/MSW students. Thematic analysis examined students’ expected knowledge and skills before, during, and after field education regarding mandatory reporting. The following themes emerged: 1) knowledge of child abuse and neglect; 2) knowledge of professional roles and boundaries; 3) knowledge of the processes involved in reporting child abuse and neglect; and 4) preparation through experiential learning. Implications for integrating legislative and ethical responsibilities into social work education are offered.

Keywords:field instructors; field education; mandatory reporting; child abuse and neglect; online survey

Child abuse and neglect is a global public health concern with negative impacts at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels of society. It is estimated one billion children around the world are exposed to childhood violence each year (Hillis et al., 2016). According to the 2014 General Social Survey (GSS), approximately 10 million, or one-third (33%) of Canadians reported experiencing at least one form of maltreatment in their childhood; however, the majority did not disclose the abuse (Burczycka, 2018).

While child welfare prevention and interventions have existed for well over a century in Canada, mandatory reporting legislation is relatively new. The province of Ontario first enacted mandatory reporting laws in 1965, followed shortly by other provinces, and by 1981 all Canadian provinces had adopted mandatory reporting for child abuse (Tonmyr et al., 2018). In most Canadian provinces and territories, suspected child maltreatment should be reported to local Child Protection Services (CPS), delegated First Nations Child and Family Service Agencies (FNCFSA), or Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), who are legally obligated to report to CPS (Government of Canada, n.d.). Social work students and field instructors (FI) have a legal and ethical obligation to determine the necessity of contacting CPS and reporting if needed. This study surveyed Canadian FIs on their perspectives of how schools of social work prepare social work students for encountering situations of child abuse and neglect.

Literature Review

Mandatory Reporting

Social workers have a fiduciary and ethical responsibility to report suspected child abuse and neglect (Canadian Association of Social Workers [CASW], 2005; National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2017). Mandatory reporting has led to increased reports of child maltreatment (Tonmyr et al., 2018), serving as a safety measure in place for victimized children and youth (Mathews & Bross, 2008). It is also effective in revealing cases of child maltreatment, as shown in comparison data that examined jurisdictions with and without mandatory reporting (Mathews & Bross, 2008). Child maltreatment reports from mandatory reporters (social workers, law enforcement, medical professionals, and public agency workers) are more likely to be substantiated than from nonmandatory reporters (King et al., 2013; McDaniel, 2006), emphasizing the importance of the mandatory reporter’s role.

While mandatory reporting can decrease the potential for future maltreatment, studies of the therapeutic relationship following a mandatory report found that roughly a quarter of professional relationships resulted in some type of rupture in the form of decreased disclosure and engagement (Steinberg et al., 1997; Weinstein et al., 2000) or even termination (Anderson et al., 1993). However, other research reveals a strengthening of the therapeutic relationship following the report (McTavish et al., 2017). Reporting may also negatively impact the client’s trust and future disclosure of information (Tufford, 2014). In addition, reporting situations which are unsubstantiated by CPS may be disruptive to the family (Tufford, 2012) but may also result in the family receiving needed services. Given the possibility of relationship rupture, training in appropriate and sensitive reporting of alleged child abuse or neglect may help decrease or buffer some of the negative consequences associated with mandatory reporting.

Training in Mandatory Reporting

Botash (2003) asserted that training in reporting suspected child maltreatment should be part of the medical academic curriculum, as it can diminish occurrences of underreporting or unsubstantiated reports. To date, research on training in mandatory reporting has been assessed via randomized controlled trials (Alvarez et al., 2010), single-case study designs (Donohue et al., 2002), and pretest/posttest designs (Kenny, 2007).

Alvarez et al. (2010) developed a training curriculum in which 55 professionals and student mental health practitioners were randomly assigned to an intervention workshop on reporting suspected child maltreatment. The control workshop focused on ethnicity sensitivity, which “has been shown to enhance perceptions of the clinical skills of interviewers but does not explicitly address issues that are specific to reporting suspected child maltreatment” (Alvarez et al., 2010, p. 213). Participants in the first workshop demonstrated greater knowledge on reporting laws, identifying child maltreatment, and expertise in reporting (Alvarez et al., 2010). Donohue et al. (2002) provided six training sessions on reporting child maltreatment over four weeks to a third-year medical student with no prior reporting experience. The participant was then observed in role-play assessments following each training session and 45 days posttraining. Results showed skill improvement and found simulation to be a useful educational tool (Donohue et al., 2002). Kenny (2007) examined 105 education and counseling students who participated in a web-based, pretest/posttest training tutorial. The tutorial covered reporting laws and the identification of child maltreatment (Kenny, 2007). Participants rated their knowledge of reporting procedures and child maltreatment symptoms as significantly higher following the tutorial.

Tufford et al. (2019) conducted a workshop with 18 bachelor’s and 24 Masters of Social Work Students (N = 42) on decision-making and the therapeutic relationship in mandatory reporting. Following the workshop, participants read a case vignette involving physical abuse and then completed written responses to structured questions focused on decision-making and maintaining the therapeutic relationship. Participants discussed their uncertainty surrounding reporting and factors related to the client, including the client’s belief systems, as well as factors related to the social worker, such as disciplinary history, emotions, and relationship maintenance strategies.

In a multidisciplinary study, Smith (2006) sought the perspectives of undergraduate and graduate students (N = 332) on case vignettes of physical, sexual and psychological child maltreatment along with child neglect. Participants’ decision-making considered multiple perpetrator factors including age, marital status, substance use, and history of violence. Participants judged the potential for harm to be lower than the actual harm, and were challenged in viewing child neglect and psychological abuse as maltreatment. Fleming et al. (2015) examined practitioners’ (n = 40) and social work students’ (n = 105) judgment of various types of abuse (physical, neglect, sexual). The study found that students rated sexual abuse as the most concerning, and were influenced by their emotional responses to the case in comparison to practitioners. Bogo et al. (2011) tested social work students, recent graduates, and experienced social workers (N = 23) using an Objective Structured Clinical Examination in a child neglect scenario. Participants conducted a 15-minute interview with a standardized client and responded to structured reflective dialogue focusing on case conceptualization and emotional awareness. Only six participants recognized the potential for child neglect, and even fewer discussed this concern during the interview. Participants asserted uncertainty in addressing this topic with the client.

Discipline-specific training in mandatory reporting to educate future mandatory reporters has also occurred in medicine (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2021), teacher training (Baginsky & Hodgkinson, 1999), and psychology (American Psychological Association Child Abuse and Neglect Working Group, 1996). Overall, training in child abuse and neglect can highlight the prevalence of child maltreatment, as well as how to report, identify sexual abuse, and intervene with families (Alvarez et al., 2004; Bryant & Baldwin, 2010; Kenny, 2007; Krase & DeLong-Hamilton, 2015). As the relationship between mandatory reporters and CPS workers can be tenuous (Tufford & Morton, 2018), training can improve this relationship and help mandatory reporters better understand the CPS process (Bryant & Baldwin, 2010).

Social Work Field Education

Considered the signature pedagogy of social work (Council on Social Work Education [CSWE], 2015), field education plays a complementary role to academic education by which students can demonstrate the application of theory to practice (Fortune & Abramson, 1993; Kadushin, 1991). Within field education, students can witness the integration of theory and practice; deepen engagement, assessment, intervention, and termination skills; navigate ethically challenging situations; and develop self-awareness of their personal and professional selves. Students are provided the opportunity to link theory and classroom knowledge with practice, gain hands-on experience, and practice social work skills (Greeno et al., 2017; Radey et al., 2019; Tam et al., 2018).

Field education is predicated on the collaboration between schools of social work and community organizations, including schools, hospitals, agencies, the government, child welfare and long-term care agencies, shelters, and other stakeholder groups (Zendell et al., 2007). Neoliberal ideology, with its emphasis on competition, micromanagement, and fiscal restraint (Hendrix et al., 2021), has had a profound impact on field education and the quality of care provided to clients (Garrett, 2010), and has decreased the amount of time focused on individual students. Documented challenges include more complex cases, fewer financial resources, absence of workload relief, and fewer social workers able to be FIs, especially for students lacking practice experience (Domakin, 2015; Mehrotra et al., 2018). Social, economic, and political issues that affect the client, including racism, gender-based violence, and poverty, may be neglected in the training (Tecle et al., 2020), which conflicts with the core value of social justice and the ethical principle of challenging social injustice (NASW, 2017). As a result, schools of social work and field practicum sites may end up focusing on different scopes of training (Mehrotra et al., 2018; Rothman & Mizrahi, 2014), bringing confusion and incoherence to students’ education. Because of these challenges, it is crucial that schools of social work adequately prepare students to be successful in field education programs in any country and provide training to students on their obligations as mandated reporters of child maltreatment.

Field Instructors

Field instructors are practitioners with, in most cases, undergraduate or graduate social work degrees who supervise social work students in their field placements and prepare students for social work practice (Dettlaff & Dietz, 2004). While the MSW degree is the standard for FIs, many BSW and MSW placements occur in rural and remote parts of Canada where FIs with these credentials may be scarce (Unger, 2003). In these situations, social work students working towards their BSW are often supervised by FIs holding BSW credentials or even bachelor’s degree credentials. Social workers who perform the role of FIs are arguably the key educators who prepare students for social work practice. These largely volunteer roles permit FIs to “give back” to the profession, enhance their knowledge, mentor students, and teach social work skills (Bogo, 2010; Finch et al., 2019). Knowledge of mandatory reporting laws and the processes thereof encompasses this foundational aspect of social work practice. However, Krase and DeLong-Hamilton (2015) advised that globally there is no explicit directive for social work programs to train students on their mandatory reporting obligations. Thus, this aspect of social work education may fall to FIs.

Study Objective

The importance of field education, and FIs specifically, is without question, and there is a substantial body of research literature on the process and evaluation of students and FIs (Bogo, 2015; Bogo et al., 2020). Field Instructors are uniquely suited for such study given their knowledge of mandatory reporting, their roles as mentor and supervisor, and their ability to guide social work students through the processes of decision-making, reporting, and continuing psychosocial treatment with families. However, the perspectives of FIs regarding how schools of social work should prepare BSW and MSW students for mandatory reporting within the field practicum, as well as the responsibilities of FIs themselves, have not been examined in the research literature. This study seeks to fill this gap by answering the following research questions:

- What are field instructors’ perspectives of classroom and field educational roles and responsibilities for preparing students as mandatory reporters? How do field instructors’ expectations differ for BSW and/or MSW students?

- What do schools of social work need to teach students regarding child abuse and neglect prior to, during, and after field education?

- How can schools of social work support students when facing suspected child abuse and neglect in field education?

Methodology

Research Design

The first author received university Research Ethics Board approval for all study procedures, and the second author received university Research Ethics Board approval for data analysis and research dissemination. This study used a mixed methods approach. An online survey platform (Lime Survey) was used to collect quantitative and qualitative data from current, Canadian FIs. The author developed the survey in consultation with a survey design expert.

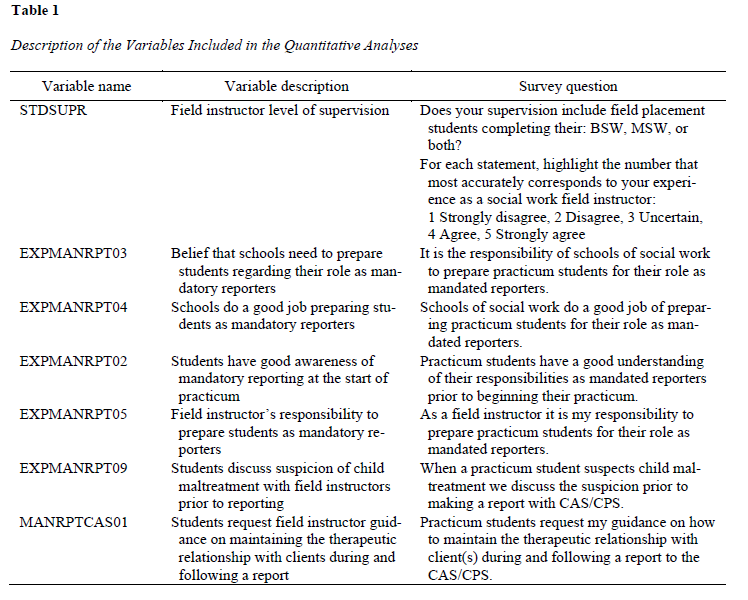

The survey comprised 15 Likert-scale questions and seven short-answer questions. The Likert-scale questions asked FIs to rate statements pertaining to their role and responsibilities with regard to educating students in the mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse and neglect. Likert-scale questions were scaled from one (strongly agree) to five (strongly disagree). The open-ended, short answer questions explored FIs’ perspectives of how schools of social work could prepare students for reporting suspected child abuse and neglect. The full set of survey questions is included in the Appendix. Table 1 outlines the variables that were derived from the survey questions.

Recruitment and Sample

The first author recruited FIs by emailing an informational letter describing the research, along with the Lime Survey weblink, to field coordinators at English schools of social work across Canada. The field coordinators were asked to forward the link to their current FIs. Participants self-selected for this anonymous survey and were assured that their responses would not impact their position as an FI. No compensation was provided to participants. A total of 58 FIs participated, with 44 FIs fully completing the demographic information, including whether they supervised BSW, MSW, or a mixed cohort of BSW/MSW students.

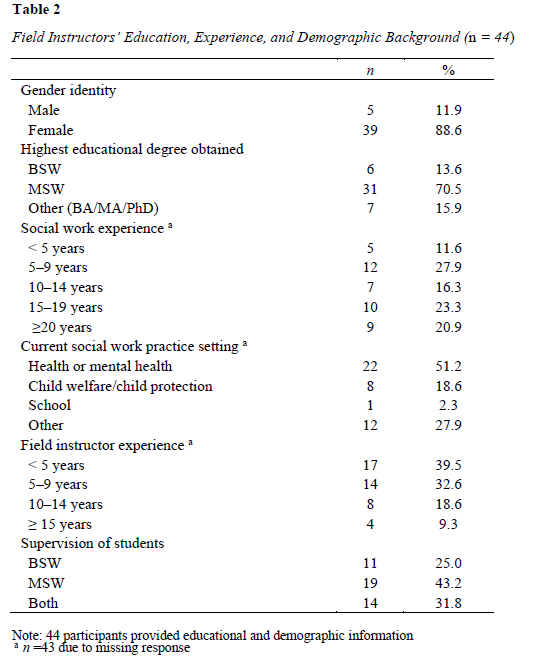

Table 2 presents the FIs’ education, experience, and demographic background (n = 44). The majority of participants were female (88.6%) with MSW degrees (70.5%) and worked within a health or mental health setting (51.2%). The FIs were experienced social workers, with over half the sample (60.5%) having over 10 years of work experience, and over a quarter (27.9%) of the sample providing field instruction for over 10 years. The majority of the sample provided field instruction for MSW students (43.2%) or both BSW and MSW students (31.8%).

Analysis

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to data analysis. The research team used IBM SPSS version 26 to analyze the quantitative data. In an a priori power analysis using G*power, researchers calculated that a sample size of 58 produces an effect of 0.4, with a 0.09 significance criterion, and 0.8 statistical power, for three groups. A power of 0.8 is deemed acceptable (Cohen, 1988) for the analyses in this study. Accordingly, means, standard deviation, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to examine differences in FIs’ perspectives of educational roles and responsibilities by program level (BSW, MSW, or mixed cohort of BSW/MSW). Normality checks and Levene’s test were conducted, and assumptions were met. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.10 because our power analysis deemed a 0.09 significance criterion to be acceptable. Further, this study is exploratory, and a more conservative threshold may yield more information to determine whether further examination is warranted.

Three authors (LT, VT, and RZ) used Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to analyze the qualitative data in NVivo 12. Responses were on three, open-ended questions regarding FIs’ expectations for schools of social work on teaching child abuse and neglect: What FIs wished schools would teach students 1) before starting their field placements; 2) during their placements; and 3) following the completion of their placements. The first step, holistic coding, entailed reviewing participants’ responses to the open-ended survey questions. Responses were then coded, and themes were developed from these initial codes. The research team met to compare and categorize codes and agree on the themes and their names until 100% consensus was reached on all coding.

Results

Field Instructors’ Experience with Mandatory Reporting

Table 3 presents participants’ experience with mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse and neglect (n = 44). While the majority of participants did not have child protection work experience (61.4%), they had received training on mandatory reporting in the past (63.6%). A large majority of participants have reported suspected child maltreatment in the past (84.1%), with over half reporting 10 or more times (51.6%). Almost half had supervised a student who reported suspected child maltreatment during field placement (45.5%) at least one time (41.2%).

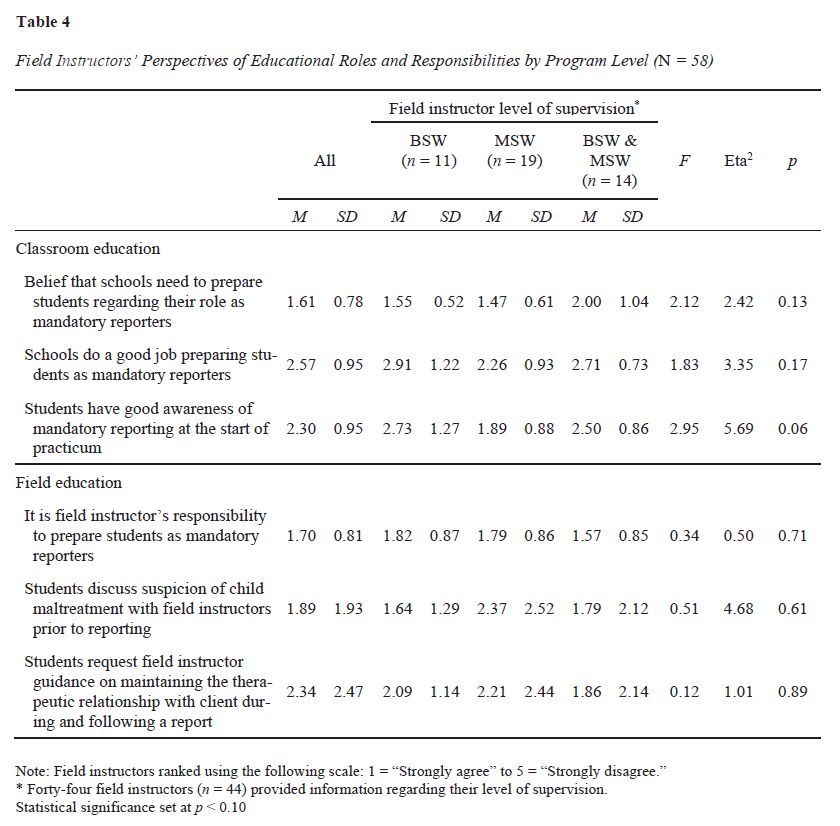

Field Instructors’ Perspectives of the Roles and Responsibilities for Student Education

Table 4 presents the one-way, between-subject analysis of variance comparing participants’ perspectives of educational roles and responsibilities by program level (BSW, MSW, and mixed cohort of BSW/MSW). Overall, participants strongly agreed that schools need to prepare students regarding their role as mandatory reporters (M = 1.61, SD = 0.78), and moderately agreed that schools do a good job preparing students as mandatory reporters (M = 2.57, SD = 0.95), and that students have a good awareness of mandatory reporting at the start of the practicum (M = 2.30, SD = 0.95). Statistical significance (p = 0.06) was found between MSW, BSW and mixed cohort of BSW/MSW students in participants’ perspective of whether students have good awareness of mandatory reporting at the start of their practicum (M = 1.89 vs. 2.73 vs. 2.50, respectively). Overall, participants thought MSW students had better awareness of mandatory reporting at the start of practicum [(F(2, 41) = 2.95, p = 0.06], thought schools do a better job preparing MSW students as mandatory reporters [(F(2, 41) = 1.83, p = 0.17], and strongly agreed that schools need to prepare MSW students regarding their role as mandatory reporters [(F(2, 41) = 2.12, p = 0.13], compared to BSW students or the mixed cohort of BSW/MSW students. This finding was supported in the qualitative data, with more participants discussing the need to teach BSWs about the reporting process prior to the start of the practicum, as compared to MSWs and the mixed cohort of BSW/MSW.

Regarding the roles and responsibilities of field education, participants strongly agreed it is their responsibility to prepare students as mandatory reporters (M = 1.70, SD = 0.81) and that students should discuss suspicions of child maltreatment with them prior to making a report (M = 1.89, SD = 1.93). Participants moderately agreed that students should request FIs’ guidance on maintaining the therapeutic relationship with clients during and following a report (M = 2.34, SD = 2.47). This finding was supported in the qualitative data, with participants noting the need to teach about policies and maintaining and repairing the therapeutic relationship during field education. There was no statistical significance in participants’ perception of field education roles and responsibilities in mandatory reporting between MSW, BSW, and mixed cohort of BSW/MSW students.

Field Instructors’ Expectations

The qualitative results describe participants’ expectations for schools of social work in regard to students’ education prior to, during, and after practicum placement. Four themes emerged from the qualitative data: 1) knowledge of child abuse and neglect; 2) knowledge of professional roles and boundaries; 3) knowledge of the processes involved in reporting child abuse and neglect; and 4) preparation through experiential learning.

Knowledge of Child Abuse and Neglect

Participants discussed the need for social work students to understand what constitutes child abuse and neglect: “What is child abuse/neglect?” (Participant #6), as well as “the different types of abuse that must be reported” (Participant #43). Participants also recognized that students may encounter less definitive situations including “scenarios that may not be so clear cut about whether there is a protection concern—to help them see the black and white within the gray” (Participant #39), and need to engage in “critical discussion of the ‘grey areas’” (Participant #30).

As part of the knowledge base of child abuse and neglect, participants identified the need for social work students to understand provincial legislation and their duty to report child abuse and neglect. Many participants referenced the specific provincial legislation: “(i.e., Section 13 and Duty to Report), the Child and Family Services Act Section 72 (1)” (Participant #29), and “The Duty to Report under the Child and Family Services Act” (Participant #33). Participants emphasized the importance of the legislation in guiding their decision-making regarding reporting suspected child abuse and neglect. For instance, one participant (#11) pointed out “it is the law. They have no choice but to report when there are suspicions that a child is at risk.” Other participants shared similar sentiments: “Any child protection concern is to be reported” (Participant #44), and “emphasize that one is making the call based on their professional beliefs that abuse/neglect may have occurred—this is based on your professional knowledge…teach the ‘Duty to Report Section’ of their region” (Participant #31).

Participants had differing opinions about where and how students gain this knowledge base. One participant indicated, “everybody has a responsibility to report. In preparation for this work they [students] should be made aware. It is the field instructor’s responsibility to ensure the student has that understanding” (Participant #50). Another participant (#55) placed the responsibility for this knowledge on the schools of social work, by noting “there should be a course on working collaboratively with Child Protection agency as a standard CORE class in order to educate every SW of the Child Welfare System and the complexities of the work.” Participants noted that schools of social work should teach students about the definitions of abuse, applicable legislation, and legal requirements before they begin field education, but did not specify whether this learning should occur during or after the field practicum.

Knowledge of Professional Roles and Boundaries

Participants discussed the need for students to be knowledgeable of their professional roles and boundaries. Engaging clients was a particular concern, as in “how to build relationships with clients” (Participant #1), “how to discuss limits of confidentiality at the beginning” (Participant #21), “outlining social work role” (Participant #18), and “[reviewing] the duty to report policy and specific agency policy and documentation required” (Participant #23). Participants were clear in demarcating their professional boundaries: “It is not your job to ‘investigate’ or to get more information prior to making the referral—that is the job of the CAS investigator” (Participant #31). This recognition of the limits of professional boundaries also applied directly to the students. One participant (#3) noted, the “student’s role is not to investigate the situation” and students need to be aware of “how to report and not to interview the child” (Participant #43).

While it is necessary to have an understanding of professional roles, participants also noted the importance of having “knowledge of how CAS support families and CAS mandate” (Participant #30), as well as “understanding the operation of [CPS]” (Participant, #37), so that this information can be transmitted to clients if needed. Participants noted that schools of social work should teach students about the role of CPS and the student’s role as a social worker before they begin field education, but did not note this necessity for during or after the field practicum. Participants did, however, note that students should learn about assessment, risk factors, and documentation during field education, as opposed to gaining this knowledge prior to or following field education.

Knowledge of the Processes Involved in Reporting Child Abuse and Neglect

Participants asserted the need for students beginning, during, and after the practicum to understand the duty to report. There was an emphasis on students being aware of the logistical process of reporting suspected child abuse and neglect to CPS prior to starting practicum, particularly for BSW students. Participants spoke of “how to make a call” (Participant #6), “what the reporting process looks like” (Participant #12), and “more understanding of how to do this” (Participant #25). Participants elucidated providing information to CPS, as in “the specifics that need to be known in order for the proper identification of a client” (Participant #46) and “know what information to provide and what information to record” (Participant #51). Participants also asserted that students need to understand the processes involved beyond reporting. One participant (#12) shared “what the investigation/apprehension can look like,” while another participant (#3) explained “options [CPS] has when investigating and possible outcomes.”

In addition to grasping the logistical processes, participants asserted that students need to understand clients’ emotional processes when reporting suspected child abuse and neglect. One participant (#2) explained that students need to engage in critical reflection and empathy in “knowing the impact it will have on the family and the child.” Another participant (#18) asserted that students can prepare by considering the “possible reactions, talk about consequences” with the clients. In addition, participants noted students should acknowledge the emotional impact on themselves prior to field education, as this can, in turn, impact the client. Moreover, during field education students should learn about debriefing and self-care after the practicum placement.

Participants also discussed the relationship-repair strategies that can be used with clients before, during, and after a report to CPS. In particular, participants indicated it is “important to openly discuss limits of confidentiality at the beginning” (Participant #21), “how to interact with the parents regarding reporting” (Participant #3), “how to continue to work with them after a report/removal” (Participant #1), and the “repair strategies when needing to do this” (Participant #25). Interestingly, participants noted this knowledge was to be accrued during the practicum, as opposed to before or after the practicum placement.

Preparation Through Experiential Learning

Participants discussed the importance of students having a variety of experiential exercises prior to the field placement to prepare them for facing child abuse and neglect. Participants suggested case scenarios and role play were effective educational exercises that can be used with students, as case scenarios, in particular, offer students the opportunity to consider clinical approaches. One participant (#3) suggested presenting written or verbal “examples of situations requiring a report” while another participant (#14) elaborated that students can “think critically about the nuances involved in various scenarios,” and instructors can “provide different scenarios that might involve reporting and have student determine how they might approach the situation” (Participant #51).

Beyond engaging with case scenarios, participants advocated for experiential learning in the form of role play with social work students prior to entering the practicum “…to give students an opportunity for practice” (Participant #3). One participant (#17) shared, “definitely role play how to share concerns with a parent and how to disclose to parent that they are reporting” and “role play scenarios where a social work student would be expected to make a report to [CPS]” (Participant #27). One participant (#51) suggested “practice mock phone calls to [CPS] to know what information to provide and what information to record.” A few participants noted the importance of ongoing opportunities for practice in the classroom after the field placement, while other participants noted that this knowledge should be solidified by students at this point.

Discussion

The study findings illustrate the dual roles of school and field experience in helping students acquire the knowledge and skills required for future social work practice. Participants strongly agreed that schools (M = 1.61, SD = 0.78), as well as FIs (M = 1.70, SD = 0.81), need to prepare students regarding their role as mandatory reporters. The transfer of knowledge to the field is predicated on the FIs’ own knowledge and comfort with mandatory reporting. The majority of FIs in the study indicated they had prior mandatory reporting training (63.6%) and had reported child maltreatment concerns in the past (84.1%). This experience allows FIs to effectively guide students in the complexity of decision-making and relationship-repair strategies.

However, students need to be prepared with foundational knowledge for application in the field. Participants discussed the need for students to understand the legislative requirements involved in reporting suspected child abuse and neglect, particularly as they are jurisdictionally defined and vary between province and state (Mathews et al., 2006). The quantitative and qualitative results both showed that participants thought schools of social work could play a critical role in providing this requisite knowledge prior to placement. Mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect should be included early in the social work curriculum, so students have this knowledge when they enter field education.

In the qualitative findings, participants further asserted that students should delineate the divergent roles of social worker and child protection worker. While completing the field education component, students are not to conduct child protection investigations. Child protection workers are trained in child development and conducting risk assessments and home visits; most social workers not employed in child protection do not possess this specialized training (Tufford & Lee, 2020). This perspective also surfaces the ethical obligation of social workers to not work outside the scope of their practice (Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers [OCSWSSW], 2008) while concurrently maintaining their statutory obligations to report suspected child maltreatment. Adopting an investigatory role may place the social worker at risk for disciplinary action by a regulatory body, and in addition may negatively impact the role a social worker has in the life of the child. For example, a social worker employed at a children’s mental health center who asks a child for detailed and potentially traumatic information that would normally be gathered by a child protection worker may irreparably disrupt the therapeutic relationship.

Participants discussed the reality that a report to CPS is often a time of great distress for clients, who may experience a range of negative emotions including fear, anger, and betrayal (Tufford, 2016). Tufford (2012) found that even when social workers clearly outlined the limits to confidentiality at the start of treatment, disclosing child abuse or neglect often elicited negative emotions from the client, despite having been clearly forewarned of the outcome of such a disclosure. Participants advised that students need to develop an empathic awareness to understand clients’ emotional processes during the reporting process. An interesting finding is that participants did not discuss potentially positive emotions and reactions by some clients, such as relief and feeling validated (Tufford, 2016).

Participants also asserted students should acknowledge the emotional impact on themselves, and practice self-care strategies to mitigate associated risks. However, few participants discussed the need for schools of social work to prepare students for the emotional impact of reporting a client to CPS. The mandatory reporting process can be distressing for students who are unaccustomed to having a conversation of this nature and may lead to significant feelings of conflict and betrayal for students (Litvack et al., 2010; Tufford et al., 2019). Discussions of reporting to CPS also occur following guarantees of client confidentiality, albeit with limits. Much of direct-practice social work education rightly focuses on the competencies involved in engaging, assessing, intervening, and terminating (CSWE, 2015) with various client formations. However, a crucial feature of working with clients is learning to hold their distress and anger when using skills such as challenging and helping clients acknowledge other perspectives (Chen & Russell, 2019).

Participants asserted the need for experiential learning around child abuse and neglect to be integrated into the social work curriculum prior to commencing field education. One participant suggested using role plays and mock phone calls to prepare students for the rigor of reporting child abuse and neglect, as they were not aware of these practices being used in their jurisdiction. Experiential exercises such as these move students beyond a cognitive or theoretical understanding to an embodied experience, which can help students understand the social, cultural, and psychological dimensions (Tangenberg & Kemp, 2002).

One experiential opportunity not discussed by participants is the use of simulation to prepare students for the mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect. There is a burgeoning body of social work literature on the use of simulation in preparing students for child welfare practice, the decision to report, and maintaining the therapeutic relationship (Lee et al., 2021; Rawlings et al., 2021; Tufford et al., 2015, 2021). This would involve students working with an actor who is trained to play a role, such as a parent who discloses abuse or neglect. Simulation provides students with a more authentic and realistic experience than role play or case study alone (Asakura et al., 2021).

Another theme not discussed by participants is the intersection of reporting suspected child abuse and neglect with culturally based disciplinary practices, which can complicate the decision-making process. Racial disproportionality, either underrepresentation or overrepresentation, in the CPS system is a reality in both Canada and the United States (Dettlaff & Boyd, 2020; Lee et al., 2016; Statistics Canada, 2011). In addition, although participants did suggest social work students have knowledge of the mandate of CPS, which is to ensure the safety and protection of children, this mandate is complicated by the Criminal Code of Canada Section 43’s permission to use “reasonable force” in the disciplining of children (Bennet, 2008). The contradiction between the mandate of the CPS and the Criminal Code of Canada can render decision-making challenging as the Criminal Code of Canada, section 43, permits the use of corporal punishment or corrective force that is considered “reasonable” “transitory and trifling” (Government of Canada, n.d.). This points to the need to be well versed in the legislation.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Due to privacy policies, schools of social work do not provide a listing of their field instructors. It was not possible to send the survey directly to FIs; rather, they were accessed via field coordinators at schools of social work. Contacting FIs directly may have resulted in a larger sample size. In addition, due to the online format of the survey, FIs who experience discomfort with completing responses online may not have responded to the survey. Furthermore, online surveys diverge from individual interviews in that they do not allow an in-depth exploration of participant responses. In addition, the survey was not assessed for reliability and validity prior to data collection, and as such, this constitutes a limitation of the study. Within the demographic information, we did not collect information on where FIs received training on mandatory reporting and what the training entailed. In addition, we also did not collect information on the geographic location of FIs, specifically, urban, suburban, rural, or remote locations. Field instructors in urban locations may have more access to training programs than those located in rural or remote areas.

Implications for Social Work Practice

Social work educators whose pedagogy centers on law and ethics, child abuse and neglect, and work with children and families may find these results helpful when preparing social work students for mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect in the field education component of their program. These implications surface from the perspectives of FIs in the present study, as well as in the child abuse and neglect research literature. In no way are they meant to imply that schools of social work are failing to address these issues in undergraduate or graduate social work; however, training in child abuse and neglect is not uniform across all schools of social work. In Canada, the BSW program or “professional years” may not begin until the second or third year of the four-year undergraduate program. In addition, students who already possess an undergraduate degree in another discipline may be eligible for a one-year BSW program in some schools of social work. In these scenarios, students’ pedagogy may or may not include information and training on mandatory reporting, depending on the required coursework. Moreover, child abuse and neglect courses are often designated as electives and offered on a rotating basis in small, underresourced schools. In this latter situation, it is an unfortunate reality that students may complete a BSW or MSW program without completing a course on child abuse and neglect.

Incorporate Legislative and Ethical Responsibilities Into the Social Work Curriculum

As noted by participants in this study, it is critical for students to understand their legislative and ethical information responsibilities. Child abuse and neglect legislation, and specifically, what constitutes “a child in need of protection,” varies by provincial and state jurisdiction. Schools of social work are encouraged to incorporate ethical and legal imperatives early in the social work curriculum in foundational courses, as well as later in the curriculum in courses such as work with children and families. In addition, discussions regarding the role and scope of a social worker, and what that role does and does not entail, can be integral to the social work curriculum. Schools of social work may consider including a mandatory course on child abuse and neglect, although this may not be possible due to competing demands in the social work curriculum.

Assist Students to Intervene With the Range of Client Emotions and Reactions

Participants in this study described negative emotions and reactions from clients to the reporting of suspected child abuse and neglect. Social workers educators are encouraged to prepare students to work with the range of client emotions, both positive and negative. One way to facilitate this, as noted by participants in this study, is the use of experiential exercises such as role plays and simulation. Experiential exercises offer social work students opportunities to discuss the need to report with clients, psychoeducation to prevent future maltreatment, repair strategies to maintain the relationship, and practice in regulating negative and conflicting emotions regarding the report. Experiential exercises can also pinpoint when students move into an investigator role and begin working outside their scope of practice.

Build Partnerships Between Schools of Social Work and Field Education

Schools of social work and field education sites have an interdependent relationship. Schools depend on the willingness of field education sites to accept their students, while many field education sites depend on students due to understaffing and government financial restraint. It is in the best interests of both to develop solid working relationships, and agreement on the requisite pedagogy around mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect is one example of this.

Integrate Mandatory Reporting Training Prior to Students Beginning the Field Placement

Participants thought that MSW students had greater awareness of mandatory reporting at the beginning of practicum than did BSW students. At the same time, they recognized their role in preparing the students to become future mandated reporters. While participants expected all students to have this requisite knowledge prior to starting practicum, FIs and schools of social work still need to work jointly in building this knowledge base, by starting the training of mandatory reporting early for BSW and MSW students.

Future Research

This study offers additional avenues for research in the intersection of field education and the reporting of suspected child abuse and neglect. Future research could explore the perspectives of FIs on students who have completed a course that covers child abuse and neglect prior to entering the practicum versus students who have not completed such a course. In addition, future research could examine the perspectives of BSW and MSW social work students regarding requisite knowledge regarding child abuse and neglect prior to entering field education. Research could also examine how schools of social work integrate legislative and ethical responsibilities into the overall curriculum, and examine the benefits of offering students brief, focused training in child abuse and neglect prior to entering field education.

Conclusion

This study sought the perspectives of Canadian FIs on the requisite knowledge of social work students with regard to the mandatory reporting of suspected child maltreatment. Field instructors asserted that knowledge of legislation, reporting processes, emotional reactions, and the social work role at the undergraduate and graduate levels were important for participation in field education when and if suspected child abuse and neglect arose. Field instructors viewed that imparting this knowledge falls within the purview of themselves and schools of social work. This perspective highlights the need for collaborative, reciprocal, and informed relationships between schools of social work and placement sites. It is critical that the academy and the field communicate fully regarding the training and knowledge needed to best prepare students for the rigors of practice.

References

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. (2021). Program requirements for graduate medical education in pediatrics.

https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/320_pediatrics_2021v2.pdf

Alvarez, K. M., Donohue, B., Carpenter, A., Romero, V., Allen, D. N., & Cross, C. (2010). Development and preliminary evaluation of a training method to assist professionals in reporting suspected child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment, 15(3), 211–218.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559510365535

Alvarez, K. M., Kenny, M. C., Donohue, B., & Carpin, K. M. (2004). Why are professionals failing to initiate mandated reports of child maltreatment, and are there any empirically based training programs to assist professionals in the reporting process? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 563–578.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2003.07.001

American Psychological Association Child Abuse and Neglect Working Group. (1996). A guide for including information on child abuse and neglect in graduate and professional education and training. American Psychological Association.

Anderson, E., Levine, M., Sharma, A., Ferretti, L., Steinberg, K., & Wallach, L. (1993). Coercive uses of mandatory reporting in therapeutic relationships. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 11(3), 335–345.

https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2370110310

Asakura, K., Gheorghe, R. M., Borgen, S., Sewell, K., & MacDonald, H. (2021). Using simulation as an investigative methodology in researching competencies of clinical social work practice: A scoping review. Clinical Social Work Journal, 49(2), 231–243.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-020-00772-x

Baginsky, M., & Hodgkinson, K. (1999). Child protection training in initial teacher training: A survey of provision in institutions of higher education. Educational Research, 41, 173–181.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188990410205

Bennet, L. (2008). The “spanking” law: Section 43 of the Criminal Code. Parliament of Canada.

https://lop.parl.ca/sites/PublicWebsite/default/en_CA/ResearchPublications/201635E

Bogo, M. (2010). Achieving competence in social work through field education. University of Toronto Press.

Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices and contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 317–324.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

Bogo, M., Regehr, C., Logie, C., Katz, E., Mylopoulos, M., & Regehr, G. (2011). Adapting Objective Structured Clinical Examinations to assess social work students’ performance and reflections. Journal of Social Work Education, 47, 5–18.

https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2011.200900036

Bogo, M., Sewell, K. M., Mohamud, F., & Kourgiantakis, T. (2020). Social work field instruction: A scoping review. Social Work Education.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1842868

Botash, A. S. (2003). From curriculum to practice: Implementation of the child abuse curriculum. Child Maltreatment, 8(4), 239–241.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559503257960

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bryant, J. K., & Baldwin, P. A. (2010). School counsellors’ perceptions of mandatory reporter training and mandatory reporting experiences. Child Abuse Review, 19(3), 172–186.

https://doi.org/10.1002/car.1099

Burczycka, M., & Conroy, S. (2018). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2016. Catalogue no. 85-002-X. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/85-002-X201800154893

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2005). Guidelines for ethical practice.

https://www.casw-acts.ca/en/what-social-work/casw-code-ethics/guideline-ethical-practice

Chen, Q., & Russell, R. M. (2019). Students’ reflections on their field practicum: An analysis of BSW student narratives. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 39(1), 60–74.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2018.1543224

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic.

Council on Social Work Education. (2015). Educational policy and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs.

https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Standards-and-Policies/2015-EPAS/2015EPASandGlossary.pdf

Dettlaff, A. J., & Boyd, R. (2020). Racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system: Why do they exist, and what can be done to address them? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 692(1), 253–274.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220980329

Dettlaff, A. J., & Dietz, T. J. (2004). Making training relevant: Identifying field instructors’ perceived training needs. The Clinical Supervisor, 23(1), 15–32.

https://doi.org/10.1300/j001v23n01_02

Domakin, A. (2015). The importance of practice learning in social work: Do we practice what we preach? Social Work Education, 34(4), 399–413.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1026251

Donohue, B., Carpin, K., Alvarez, K. M., Ellwood, A., & Jones, R. W. (2002). A standardized method of diplomatically and effectively reporting child abuse to state authorities: A controlled evaluation. Behavior Modification, 26(5), 684–699.

https://doi.org/10.1177/014544502236657

Finch, J. B., Williams, O. F., Mondros, J. B., & Franks, C. L. (2019). Learning to teach, teaching to learn (3rd ed.). Council on Social Work Education.

Fleming, P., Biggart, L., & Beckett, C. (2015). Effects of professional experience on child maltreatment risk assessments: A comparison of students and qualified social workers. British Journal of Social Work, 45(8), 2298–2316.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu090

Fortune, A. E., & Abramson, J. S. (1993). Predictors of satisfaction with field practicum among social work students. The Clinical Supervisor, 11(1), 95–110.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v11n01_07

Garrett, P. M. (2010). Examining the “conservative revolution”: Neoliberalism and social work education. Social Work Education, 29(4), 340–355.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470903009015

Greeno, E. J., Fedina, L., Rushovich, B., Burry, C., Linsenmeyer, D., & Wirt, C. (2017). The impact of a Title IV-E program on perceived practice skills for child welfare students: A review of five MSW cohorts. Advances in Social Work, 18(2), 474–489.

https://doi.org/10.18060/21058

Government of Canada. (n.d.). Child maltreatment: A “what to do” guide for professionals who work with children.

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/stop-family-violence/prevention-resource-centre/children/child-maltreatment-what-guide-professionals-who-work-children.html

Hendrix, E., Barusch, A., & Gringeri, C. (2021). Eats me alive!: Social workers reflect on practice in neoliberal contexts. Social Work Education, 40(2), 161–173.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1718635

Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3).

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4079

Kadushin, A. E. (1991). Introduction. In D. Schneck, B. Grossman, & U. Glassman (Eds.), Field education in social work: Contemporary issues and trends (pp. 11–12). Kendall/Hunt.

Kenny, M. C. (2007). Web-based training in child maltreatment for future mandated reporters. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(6), 671–678.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.008

King, B., Lawson, J., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2013). Examining the evidence: Reporter identity, allegation type, and sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of maltreatment substantiation. Child Maltreatment, 18(4), 232–244.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559513508001

Krase, K. S., & DeLong-Hamilton, T. A. (2015). Preparing social workers as reporters of suspected child maltreatment. Social Work Education, 34(8), 967–985.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1094047

Lee, B., Fuller-Thomson, E., Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., & Black, T. (2016). Delineating disproportionality and disparity of Asian- Canadian versus White-Canadian households in the child welfare system. Child and Youth Services Review, 70, 383–393.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.023

Lee, B., Ji, D. & O’Kane, M. (2021). Examining cross-cultural child welfare practice through simulation-based education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 42(2), 271–285.

Litvack, A., Mishna, F., & Bogo, M. (2010). Emotional reactions of students in field education: An exploratory story. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(2), 227–243.

https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2010.200900007

Mathews, B., & Bross, D. C. (2008). Mandated reporting is still a policy with reason: Empirical evidence and philosophical grounds. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(5), 511–516.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.06.010

Mathews, B., Walsh, K., Butler, D., & Farrell, A. M. (2006). Mandatory reporting by Australian teachers of suspected child abuse and neglect: Legislative requirements and questions for future direction. Australia & New Zealand Journal of Law & Education, 11(2), 7–22.

McDaniel, M. (2006). In the eye of the beholder: The role of reporters in bringing families to the attention of child protective services. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(3), 306–324.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.04.010

McTavish, J. R., Kimber, M., Devries, K., Colombini, M., MacGregor, J. C. D., Wathen, C. N., Agarwal, A., & MacMillan, H. L. (2017). Mandated reporters’ experiences with reporting child maltreatment: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. British Medical Journal, 7(10), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1136%2Fbmjopen-2016-013942

Mehrotra, G. R., Tecle, A. S., Ha, A. T., Ghneim, S., & Gringeri, C. (2018). Challenges to bridging field and classroom instruction: Exploring field instructors’ perspectives on macro practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(1), 135–147.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1404522

National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Code of ethics.

https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers. (2008). Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice Handbook.

https://www.ocswssw.org/wp-content/uploads/Code-of-Ethics-and-Standards-of-Practice-September-7-2018.pdf

Radey, M., Schelbe, L., & King, E. A. (2019). Field training experiences of child welfare workers: Implications for supervision and field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(1), 134–145.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0669-2

Rawlings, M. A., Olivas, V., Waters-Roman, D., & Tran, D. (2021). Developing engagement competence for public child welfare: Results of an inter-university simulation project. Clinical Social Work Journal, 49(2), 172–183.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00798-9

Rothman, J., & Mizrahi, T. (2014). Balancing micro and macro practice: A challenge for social work. Social Work, 59(1), 91–93.

https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swt067

Smith, M. (2006). What do university students who will work professionally with children know about maltreatment and mandated reporting? Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 906–926.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.10.003

Statistics Canada. (2011). National household survey. Government of Canada.

https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Steinberg, K. L., Levine, M., & Doueck, H. J. (1997). Effects of legally mandated child-abuse reports on the therapeutic relationship: A survey of psychotherapists. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67(1), 112–122.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080216

Tam, D. M. Y., Brown, A., Paz, E., Birnbaum, R., & Kwok, S. M. (2018). Challenges faced by Canadian social work field instructors in baccalaureate field supervision. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 38(4), 398–416.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2018.1502228

Tangenberg, K. M., & Kemp, S. (2002). Embodied practice: Claiming the body’s experience, agency, and knowledge for social work. Social Work, 47(1), 9–18.

https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/47.1.9

Tecle, A., Mehrotra, G., & Gringeri, C. (2020). Managing diversity: Analyzing individualism, awareness, and difference in field instructors’ discourse. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(4), 683–695.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1661908

Tonmyr, L., Mathews, B., Shields, M. E., Hovdestad, W. E., & Afifi, T. O. (2018). Does mandatory reporting legislation increase contact with child protection? A legal doctrinal review and an analytical examination. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–12.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5864-0

Tufford, L. (2012). Clinician mandatory reporting and maintenance of the therapeutic alliance (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Tufford, L. (2014). Repairing alliance ruptures in the mandatory reporting of child maltreatment: Perspectives from social work. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 95(2), 115–121.

https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.2014.95.15

Tufford, L. (2016). Reporting suspected child maltreatment: Managing the emotional and relational aftermath. Journal of Family Social Work, 19(2), 100–112.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2016.1160262

Tufford, L., Bogo, M., & Asakura, K. (2015). How do social workers respond to potential child neglect? Social Work Education: The International Journal, 34(2), 229–243.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2014.958985

Tufford, L., Bogo, M., Katz, E., Lee, B., & Ramjattan, R. (2019). Reporting suspected child maltreatment: Educating social work students in decision making and maintaining the relationship. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(3), 579–595.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1600442

Tufford, L., & Lee, B. (2020). Relationship repair strategies when reporting child abuse and neglect. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37, 235–249.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00656-6

Tufford, L., Lee, B., Bogo, M., Wenghofer, E., Etherington, C., Thieu, V., & Zhao, R. (2021). Decision‑making and relationship competence when reporting suspected physical abuse and child neglect: An Objective Structured Clinical Evaluation. Clinical Social Work Journal, 49, 256–270.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-020-00785-6

Tufford, L., & Morton, T. (2018). Social work perspectives of the Children’s Aid Society. Critical Social Work, 19(1), 86–102.

Unger, J. M. (2003). Supporting agency field instructors in Forgotonia. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 23(1-2), 105–121.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v23n01_08

Weinstein, B., Levine, M., Kogan, N., Harkavy-Friedman, J., & Miller, J. M. (2000). Mental health professionals’ experiences reporting suspected child abuse and maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(10), 1317–1328.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00191-5

Zendell, A. L., Fortune, A. E., Mertz, L. K. P., & Koelewyn, N. (2007). University-community partnerships in gerontological social work: Building consensus around student learning. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 50(1-2), 155–172.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v50n01_11

Appendix

Mandatory Reporting of Child Maltreatment:

International Perspectives of Field Instructors

Please note for the purposes of the survey:

1) Children’s Aid Society will be referred to by the acronym CAS;

2) Child Protective Services will be referred to by the acronym CPS;

3) “Relationship Repair Strategies” are strategies used to repair the therapeutic relationship with the client during and/or following the mandatory reporting of suspected child maltreatment to CAS/CPS.

For each statement, highlight the number that most accurately corresponds to your experience as a social work field instructor.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Uncertain | Agree | Strongly Agree |

1. I have a good understanding of the responsibilities of social workers as mandated reporters of suspected child maltreatment.

1 2 3 4 5

2. Practicum students have a good understanding of their responsibilities as mandated reporters prior to beginning their practicum.

1 2 3 4 5

3. It the responsibility of schools of social work to prepare practicum students for their role as mandated reporters.

1 2 3 4 5

4. Schools of social work do a good job of preparing practicum students for their role as mandated reporters.

1 2 3 4 5

5. As a field instructor it is my responsibility to prepare practicum students for their role as mandated reporters.

1 2 3 4 5

6. As a field instructor it is my responsibility to advise practicum students of the consequences for failing to report suspected child maltreatment.

1 2 3 4 5

7. As a field instructor it is my responsibility to review with practicum students the specific policies of the practicum organization as they relate to the mandatory reporting of child maltreatment.

1 2 3 4 5

8. It is the student’s responsibility to learn the specific policies that the practicum organization has regarding the mandatory reporting of child maltreatment.

1 2 3 4 5

9. When a practicum student suspects child maltreatment we discuss the suspicion prior to making a report with CAS/CPS.

1 2 3 4 5

10. When a practicum student reports suspected child maltreatment to the CAS/CPS, I debrief the experience with the student.

1 2 3 4 5

11. Practicum students request my guidance on how to maintain the therapeutic relationship with client(s) during and following a report to the CAS/CPS.

1 2 3 4 5

12. It is my responsibility as a field instructor to provide guidance around the maintenance and/or repair of the therapeutic relationship following a student filing a report to the CAS/CPS.

1 2 3 4 5

13. I agree with the mandate of CAS/CPS.

1 2 3 4 5

14. My views of CAS/CPS impact my work with parents/caregivers/families.

1 2 3 4 5

15. Please indicate if the agency or organization by which you are employed has a policy specific to making a decision to report to CAS/CPS.

Yes No I do not know

Please respond with a narrative to the following questions, or enter N/A if the question does not apply.

16. What do you do when making the decision to report to the CAS/CPS (i.e., speak with a supervisor first, make an anonymous call to the CAS/CPS, complete an agency form)?

17. What do you do to prepare practicum students for sound decision-making regarding a report to the CAS?

18. What relationship repair strategies do you teach practicum students?

19. What would you like schools of social work to teach students regarding mandatory reporting before they begin field practicum?

20. What would you like schools of social work to teach students regarding relationship repair strategies during/after field practicum?

21. What would you like schools of social work to teach students regarding relationship repair strategies before field practicum?

22. What would you like schools of social work to teach students regarding relationship repair strategies during/after field practicum?