Abstract

To assess evolving trends in practicum education, a national exploratory survey (N = 186) was conducted among practicum directors within CSWE-accredited programs. Findings indicate 69% (n = 115) believe unpaid internships are a social justice issue that impedes student success. Most practicum directors (n = 133) report advocating for paid internships, though half (n = 104) report dissatisfaction with departmental support. Practicum directors deliver the signature pedagogy of social work education and are best positioned to identify needs and opportunities for change, yet their offices are often underresourced. Implications for practicum education and the profession, as well as future research recommendations, are presented.

Keywords: practicum directors; practicum education; equity; social justice; paid internships

College internships provide essential training opportunities for students to gain relevant skills in and exposure to a particular field of study. Internships benefit students, employers, and universities. Students participating in an internship receive increased access to employment opportunities, enjoy expanded professional networks, receive discipline-specific skills, earn higher starting salaries, report positive rates of job satisfaction, and are more likely to be retained within their place of employment (Binder et al., 2015; Forbes Human Resources Council, 2022; Gault et al., 2010; Huhman, 2024; Judge et al., 2001; National Association of Colleges and Employers [NACE], 2023; National Survey of College Internships [NSCI], 2021; Porter, 2019). These benefits extend beyond the workplace and include personal growth in areas such as cultural awareness, communication, and teamwork skills (Finch et al., 2013; Moran, 2013; Stack & Fede, 2017). Further, employers consider completion of an internship as a key factor involved in hiring decisions among new graduates (Finch et al., 2013; Porter, 2019; Rothschild & Rothschild, 2020). In fact, the annual NACE survey (2023) indicates employers report a streamlined and less costly onboarding process when hiring interns; this results in up to 60% of interns being hired as full-time employees. Additionally, universities experience benefits from student internships, including higher rates of student job placement postgraduation, increased revenue, and cost savings when classroom credits are obtained through off-site learning (McHugh, 2017).

While the scholarly literature has documented the benefits of internships, the related negative impacts have been a source of ongoing debate (Coker, 2009; McHugh, 2017; Svacina, 2012). Most recently, these concerns have been amplified by the cost of higher education and the COVID-19 pandemic (Morris, 2023). Although legally justified through legislation such as the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 and the FLSA Guidelines of 2018, unpaid internships may allow more protections to the employer than to the student (Rothschild & Rothschild, 2020; Svacina, 2012; Yamada, 2016). Students from marginalized groups face increased risks related to unpaid internships, thus reinforcing the widening divide between affluent and economically disadvantaged students (Eisenbrey, 2012; Shethji & Mayo, 2011). For example, unpaid internships place financial strains on students from lower socioeconomic groups, thus limiting their opportunity to participate (Eisenbrey, 2012; Shethji & Mayo, 2011). Notably, multiple studies indicate women and Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) are overrepresented in the 40% of students enrolled in unpaid internships (Fennell, 2023; Gardner, 2010; NACE, 2019, 2023). The literature indicates negative findings associated with unpaid internships compared to paid internships, including students’ experiencing a less structured work environment, limited focus from employers to ensure career readiness, and overall greater student dissatisfaction (Bussell & Forbes, 2002; Hager & Brudney, 2004; Roggow, 2014; Rothschild & Rothschild, 2020). The postgraduation implications for students participating in unpaid internships, compared to those with compensated internships, include fewer numbers of, and a delay in, job offers, as well as lower starting salaries (Crain, 2016; Guarise & Kostenblatt, 2018; NACE, 2019; Zilvinskis et al., 2020).

While the number of paid opportunities is growing, most uncompensated internships come from the social service and nonprofit sectors, which are traditionally fields with lower paying positions and higher numbers of women and BIPOC students (Boskamp, 2023; Crain, 2016; Gardner, 2010; Waxman, 2018). This may negate the importance of, and adds to the decreased enrollment in, areas of study designed to impact the public good. For example, schools of social work are committed to enhancing the well-being of individuals and the broader community, yet they report declines in undergraduate enrollment over the last decade, and have noted a more recent decline in master’s enrollment in 2021 (Council on Social Work Education [CSWE], 2021).

Although internships remain highly encouraged for many disciplines, practicum education is designated as the signature pedagogy of social work education and is a mandated requirement for graduation (CSWE, 2008, 2022). The minimum required 400 hours for undergraduate and 900 hours for graduate students far surpass the typical two-to-three-month internship requirements for other college majors (NSCI, 2021). While students and faculty largely agree that practicum education is a fundamental component of the degree (Bogo, 2015; Wayne et al., 2010), there is mounting concern about the inequities and stressors of unpaid social work internships. In response to the concerns regarding unpaid internships, the CSWE (2022) released a statement highlighting the educational and training role afforded students who do not yet meet the educational and licensing requirements necessary for paid employment. At the same time, the CSWE cited that 30% of students receive some form of monetary support, and vowed to continue their advocacy to increase funding opportunities to reduce the cost of social work education (CSWE, 2022).

In response to the rising cost of higher education, the skyrocketing cost of living, and the desire to elevate the profession, social work students have begun organizing for paid placements. Payment for Placements (P4P) is one of the fastest growing student groups involved in these advocacy efforts, with chapters at over 30 universities nationwide (Alonso, 2023). In response to these growing demands, universities and state legislators are beginning to explore funding initiatives to increase paid social work internships (National Association of Social Workers—Massachusetts Chapter [NASW-MA], 2024; National Association of Social Workers—Illinois Chapter [NASW-IL], 2024; National Association of Social Workers—Ohio Chapter [NASW-OH], 2024; Skeen, 2022). Though these efforts are increasing, there is still much work to be done to address this on a national level.

The paradox that social work internships are both an integral component of and a potential barrier to the educational experience of students warrants further examination. The social work practicum director, responsible for administering the signature pedagogy of social work education, is uniquely positioned to address these issues. For purposes of this study, the term internship is defined as a learning opportunity that enables a student to apply academic knowledge and theory within a professional setting under the direction of a qualified supervisor (NACE, 2023). Further, for the purposes of this study, the term practicum director is used to encompass social work practicum faculty with responsibilities related to student internship/placement, regardless of their institutional title (e.g., field director, field coordinator, assistant field director, etc.). This study aimed to explore practicum education faculty’s perspectives on the state of paid internship/placements available within their individual institutions. A secondary aim of the study was to explore practicum education faculty’s level of agreement regarding unpaid internships/placements being an equity and social justice barrier to social work education.

Methods

The authors used convenience sampling through our access to listservs existing in CSWE-accredited schools, allowing us to capture participants across the United States. Specifically, listservs accessed included the CSWE-managed Field Director Listserv, the MSW Listserv, and the BPD Listserv managed by Indiana University. This sampling method was used to intentionally select participants with the requisite knowledge and experience required for the study’s aim. To increase response rates, snowball sampling was utilized, as listserv members were invited to share the survey with colleagues who were not listserv participants. Inclusion criteria for the sample included those currently employed as a practicum/field director, assistant practicum/field director, practicum/field coordinator, or assistant practicum/field coordinator at a CSWE-accredited MSW and/or BSW program in the United States. To avoid redundancy in data collection, participants were asked to confirm that they were the sole social work practicum education faculty completing the survey for their program.

Measure

The original survey included a total of 21 items; for purposes of this study, 17 items were analyzed. Due to the nature of the present study, four items were not analyzed; two of these examined the number of internship/practicum hours required by the program, and two were qualitative in nature and will be explored in future research. The initial five items analyzed in this study collected programmatic information on the type and level of social work program, CSWE regional location, level of racial and/or ethnic diversity among students, percentage of students in paid placement settings, and types of paid placements available. Likert scale items asked participants to rate their agreement regarding a series of statements about the level of paid internship placements at their college/university. Participants were also asked if their college/university, compared to other institutions, offers innovative solutions to provide paid internship placements. Finally, participants were asked to rate their level of agreement regarding unpaid internships being an equity and social justice barrier in social work education. These items were scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree).

Analysis

The study was administered electronically via Qualtrics. All responses were collected anonymously and data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27. Descriptive statistics were conducted to calculate frequencies of participant responses. This study was approved by the authors’ institutional review board (IRB).

Results

One hundred and eighty-six participants responded to the survey. In regard to CSWE (2020)-defined regions, 25% (n = 47) were from the Great Lakes, 18% (n = 34) were from the Southeast, 11% (n = 20) were from the Mid-Atlantic, 9% (n = 16) were from the South Central, 9% (n = 16) were from the Northeast, 8% (n = 14) were from New England, 6% (n = 11) were from the Mid-Central, 6% (n = 11) were from the South Central, 4% (n = 7) were from the Northwest, and 3% (n = 6) were from the West. In regard to the types of social work education programs offered, 89% (n = 165) had an on-campus BSW program, 18% (n = 34) had an online BSW program, 69% (n = 129) had an on-campus MSW program, and 39% (n = 72) had an online MSW program.

When asked to rate their agreement with the statement, “The college/university where I work has a high level of racial and/or ethnic diversity among students in social work program,” 53% (n = 99) agreed or strongly agreed, 13% (n = 24) were neutral/had no opinion, and 33% (n = 61) disagreed or strongly disagreed.

The majority of participants (67%, n = 124) indicated 1–24% of their students had paid internship placements, while 13% (n = 25) reported that paid internship placements were not offered. Eighteen participants (10%) indicated that 25–49% of their students had paid internship placements, while 4% (n = 7) reported that 50–74% of students had paid internship placements. One percent (n = 2) reported that 75–100% of students in paid internship placements, and 5% (n = 10) did not know. Of those who indicated that paid internship placements were offered, funding for such placements came from a variety of sources: 35% (n = 65) offered funding via grant stipends, 15% (n = 27) via university scholarships, and 84% (n = 157) from stipends/payments connected to the internship placement site.

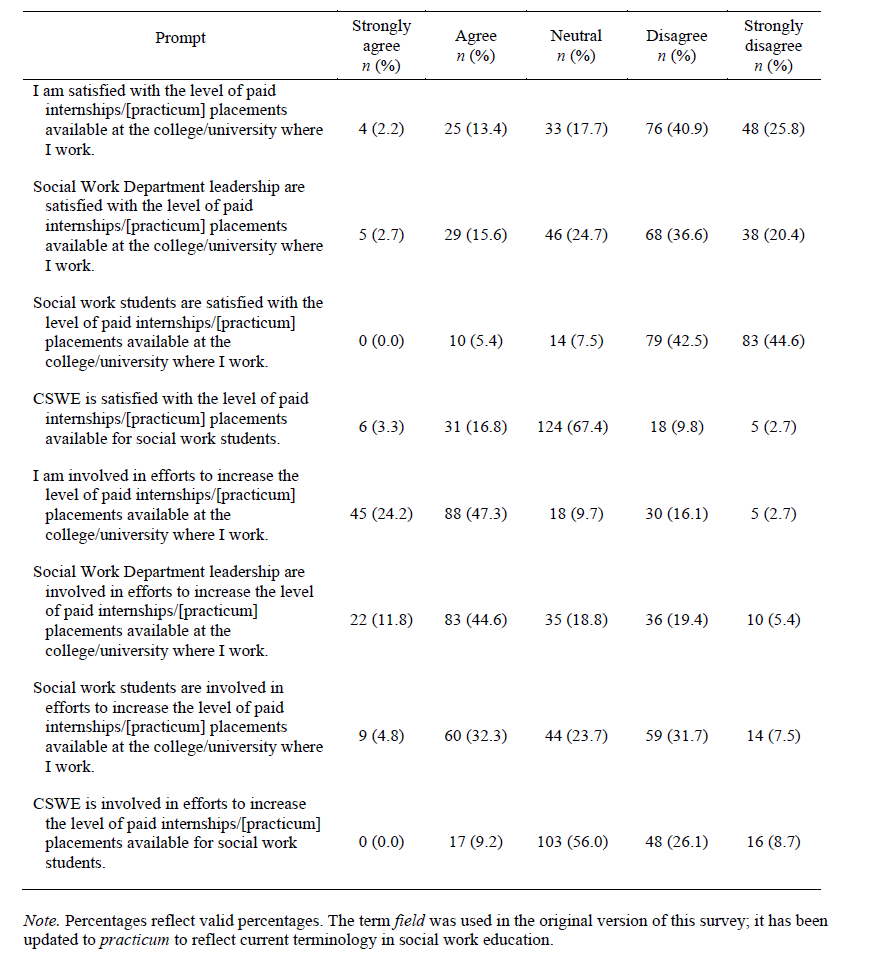

Results of the descriptive statistical analysis indicated 67% (n = 124) of practicum directors, 57% (n = 106) of social work departmental leadership, and 87% (n = 162) of students disagreed or strongly disagreed that they were satisfied with the “level of paid internships/placements available” at their college/university. When asked about involvement in efforts to increase the level of paid internships/placements available at their college/university, 72% (n = 133) agreed or strongly agreed that they were personally involved, 56% (n = 105) agreed or strongly agreed their social work department leadership was involved, and 37% (n = 69) agreed or strongly agreed that social work students were involved. Most participants (n = 103) had no opinion in regard to CSWE’s involvement. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Participants’ (N=186) Overall Satisfaction and Efforts to Increase Paid Internships

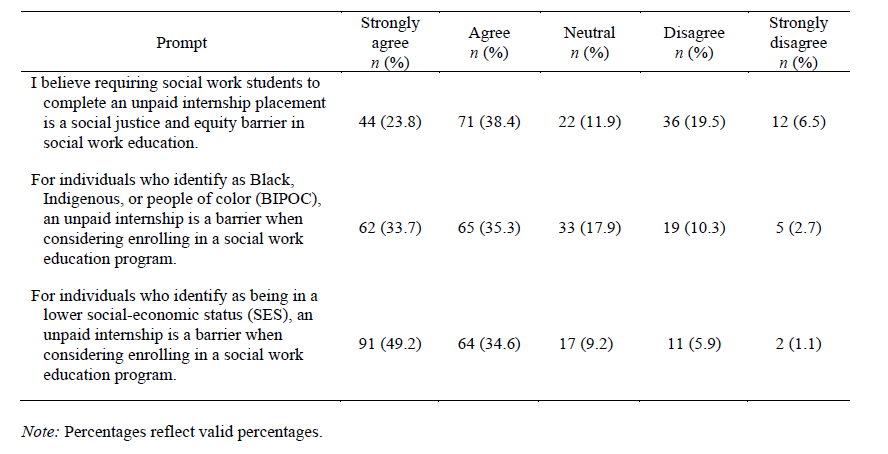

When asked to compare themselves to other institutions, 33% (n = 62) agreed or strongly agreed, 29% (n = 53) were neutral, and 38% (n = 71) disagreed or strongly disagreed that the college/university where they work offers innovative solutions to provide paid internships/placement to social work students. The majority of participants, 69% (n = 115) agreed or strongly agreed that “requiring social work students to complete an unpaid internship/placement is a social justice and equity barrier within social work education.” Likewise, participants overwhelmingly agreed that “an unpaid internship is a barrier when considering enrolling in a social work education program” for individuals who identify as BIPOC (n = 127) or as being in a lower socioeconomic status (n = 155) respectively. (See Table 2.)

Table 2

Participants’ (N=186) Agreement Regarding Unpaid Internships as a Social Justice and Equity barrier

Discussion

Findings from this study indicate that 67% (n = 124) of practicum education directors surveyed are dissatisfied with the level of paid internship opportunities for social work students at their institutions. The vast majority of respondents (72%, n = 133) reported being professionally involved in efforts to increase the level of paid internship placements for students. While this can be seen as positive, historically practicum education directors have expressed having a lack of adequate resources, support, and staff to provide quality student placements; recruit and retain agencies to provides these experiences; and administer the program of practicum education (Ayala et al., 2018; Beaulieu, 2020; Lyter, 2012; Wertheimer & Sodhi, 2014). Given the landscape of practicum education, these challenges present additional difficulties to practicum education directors who wish to increase paid internship opportunities. The majority of practicum education directors’ job responsibilities do not specifically include securing paid internship opportunities or potential funding sources to support student placements; however, the data revealed many are now taking on this challenge, to increase student success. Shouldering the responsibility of increasing paid internship opportunities, in an attempt to meet student need, may pose an increased potential for burnout in the practicum education director role, an issue well defined in the literature (Beaulieu, 2020; Chiarelli-Helminiak et al., 2022; Ellison & Raskin, 2014; Grise-Owens et al., 2016; Holcomb, 2024). Additionally, there have been significant changes relating to the use of work-based placements. The relaxing of CSWE’s stance on such placements has allowed programs to pursue these avenues to increase paid placements; however, there are inherent challenges within these practicum arrangements. While this topic is beyond the scope of the article, this is an area ripe for future research.

According to our research, practicum education directors are assuming leadership in the area of paid internship development, yet the level of advocacy and support from those in social work departmental leadership positions is not adequate. According to respondents, only 56% (n = 105) indicated their social work departmental leadership colleagues are actively engaged in working to address this issue. This lack of broader programmatic and administrative support may leave practicum education directors feeling isolated and unable to address this significant issue. Practicum education directors’ concerns regarding lack of support have been well documented for the past 20 years (Ayala et al., 2018; Beaulieu, 2020; Lager & Robbins, 2004; Lyter, 2012; Wertheimer & Sodhi, 2014). While practicum education has been designated as the signature pedagogy of social work education, many practicum education directors hold a lower academic rank and status, lack parity with tenure-track faculty, are often excluded in matters of institutional governance and program leadership, and struggle to fit within the traditional university setting and norms (Ayala et al., 2018; Beaulieu, 2020; Wertheimer & Sodhi, 2014). Additionally, practicum education offices are often woefully understaffed and underresourced, furthering the perception that practicum education directors are not as valued as their tenure-track counterparts, despite the “signature pedagogy” designation (Lyter, 2012; Wertheimer & Sodhi, 2014).

Further, respondents stated that only 37% (n = 69) of students at their institutions were actively involved in advocacy work regarding paid internships. While the student-led Payment for Placement (P4P) movement is gaining momentum across the country, natural attrition due to graduation may present a barrier to sustained engagement of students. Our social work values require us to address issues of parity and equity as well as to advocate for more inclusive practices as they relate to paid internship opportunities; however, the lack of consistent student involvement, coupled with the absence of robust departmental leadership support, creates an unfair burden on the practicum education director. While practicum education directors empathize and understand the barriers created by unpaid internships, findings indicate there is a lack of program-level planning at many institutions.

The majority of respondents (80%, n = 149) indicated that less than 25% of their students received paid internships. Additionally, 13% of respondents (n = 25) reported that their institutions do not offer any paid placement options for students. While the lack of payment options presents an issue for the entire student population, the majority of respondents, 62% (n = 115), believe that not providing compensation for internships is a social justice and equity issue that negatively impacts historically marginalized students disproportionately. While paid placements positively impact the student body more broadly, there is research to suggest additional benefits to long-term student success, particularly for students who are members of the following groups: first-generation students, female students, parents, those from families with lower socioeconomic status, and BIPOC students (de Bie et al., 2021; Hodge et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2021; Lynch et al., 2023, Zilvinskis et al., 2020). While 53% of respondents (n = 99) indicated their social work students represent high levels of racial/ethnic diversity, this is an area that needs continued focus, particularly considering the 2022 CSWE Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS) mandates around issues of social justice, antiracism, diversity, equity, inclusion, and representation (CSWE, 2022). This should be an area of focus for all social work educators, including practicum education directors, as there are historical roots and current concerns around unpaid internships perpetuating systems of oppression, marginalization, and racism (de Bie et al., 2021; Dill et al., 2023: Hodge et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2021; Lynch et al., 2023, Zilvinskis et al., 2020). If social work is truly to actualize its mission and live the core values of the profession, it is incumbent upon those in higher education to reduce barriers that exclude historically marginalized students from entering, and succeeding, in the profession. One such area that is ripe for exploration is the role internships have in perpetuating this disparity.

Implications for Higher Education

As the climate of practicum education continues to change and evolve rapidly, it is critical to assess practicum education director and programmatic responses to student and community partner needs. While maintaining rigorous standards and expectations for the signature pedagogy of social work education is required, programs should conduct a thorough assessment of internship policies and procedures to ensure fairness and equity for all students. Programs must conduct a critical evaluation of whether their policies and processes create unnecessary barriers to student success, and seek feedback on any unintended consequences. This is a requirement given the new 2022 EPAS standards related to implicit and explicit curriculum (CSWE, 2022), as well as our mandate to deliver a truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive education. An honest assessment is particularly important as it relates to historically marginalized students and to addressing issues of representation within the profession. As social workers, it is critical that those in practicum education work to increase representation within the profession and the communities and clients that are served.

In light of these requirements, and the need within our profession to truly act from an ADEI (antiracist, diverse, equitable, and inclusive) and social justice–oriented lens, it is critical that leadership within social work programs, as well as in their accrediting body, demand that practicum education offices are fully resourced and staffed. This important work cannot be one more responsibility added to practicum education directors’ already heavy loads. To ensure this issue is given the attention it deserves, the accrediting body should consider being more prescriptive in the resourcing of practicum education offices. Without a strong statement from CSWE, practicum education directors will not be able to address fully the issues that persist as they relate to equity in internships and extend into the profession.

Future Research

As this study is exploratory, there is opportunity for future research. Capturing the voices of practicum education directors across the nation is critical to understanding the evolving nature and complexities of practicum education. It is important to explore how practicum education directors balance meeting student and agency needs while adhering to CSWE accreditation standards. Additionally, it is crucial to gather information that promotes best practices in areas such as reducing student barriers to engaging in and successfully completing their internships. Practicum education directors across the country do important work and may already be establishing best practices to address issues related to equity within practicum education; however, this information needs to be shared widely to support the broader community. Issues of payment for internships; equity and representation, particularly for historically marginalized groups; mental health support; the ability to meet the needs of agency partners; and the significant workforce challenges currently present are areas ripe for research. There is also a great need to explore creative ways to increase levels of paid internships and to identify diverse funding pools to assist in these endeavors. Further, while practicum education directors are responsible for the administration and oversight of practicum education, they do not do so in a vacuum. Understanding the ways in which successful internship offices obtain support from their programs, colleges, and broader institutions could result in developing best practices to be modeled. Finally, research on practicum education directors’ perceptions of satisfaction with the support received from the accrediting body would be helpful to understand how best to assist those tasked with administering the signature pedagogy of social work education.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study is a beginning attempt to gain further understanding of the inequities and complex issues impacting internships within social work education. Understanding the voices of those in practicum education director positions is critical to identifying current trends, challenges, and creative solutions that are being employed throughout practicum education. This is particularly important given that practicum education has been deemed the signature pedagogy of social work education.

While there are strengths within this study, there are limitations. All CSWE regions were represented within this study; however, there are some areas that were more heavily represented, and so findings may not be representative of practicum education directors across the country. Additionally, individual participant demographic information was not obtained; while this choice was intended to ensure anonymity, the authors recognize the resulting limitations to analysis and the potential implications of this choice. Although practicum education directors are employed within every accredited social work program, the community remains quite small and connected; therefore, asking participants to disclose their demographic information, particularly when coupled with the region they work in, could lead to identification. This survey used nonprobabilistic sampling, which is a limitation. As with any survey research, there are concerns related to the lack of accounting for the complex and dynamic nature, and thus potential oversimplification, of our social reality (Jerrim & de Vries, 2017). As this study asked participants to self-report their own attitudes on issues impacting practicum education, and in some cases their specific involvement on advancing paid internship placements, desirability issues may be present (Morgado et al., 2017). Participants reported their attitudes and so are representative of the particular sample; however, results cannot be generalized to settings and populations beyond the responses obtained. As this survey has not been replicated, reliability should be considered. Finally, as this study is exploratory in nature, causality cannot be inferred; however, the data that were captured provides rich information to explore.

Conclusion

Student success within practicum education is an important topic for social work education and the profession more broadly. Issues related to equity and inclusion are reflected in the literature both during internships and within the broader workforce. While practicum education directors are committed to addressing issues of equity within practicum education, there are many obstacles that may prevent this important work. It is paramount that social work programs, institutions, and the accrediting body prioritize meaningful ways to support paid student internships. The shift towards paid placements aligns with the core values of social work, responds to student needs, and makes progress towards developing a workforce that is representative of the individuals and communities the profession serves. To truly actualize ADEI mandates, social work education must prioritize creating meaningful ways to rethink internship requirements, as well as providing concrete support regarding paid internships.

References

Alonso, J. (2023, May 10). Seeking payment for social work internships. Inside Higher Education.

https://tinyurl.com/3umya9c8

Ayala, J., Drolet, J., Fulton, A., Hewson, J., Letkemann, L., Baynton, M., Elliott, G., Judge-Stasiak, A., Blaug, C., Tétreault, A. G., & Schweizer, E. (2018). Restructuring social work field education in 21st century Canada. Canadian Social Work Review, 35(2), 45–65.

https://doi.org/10.7202/1058479ar

Beaulieu, S. R. (2020). The training and mentoring of social work field directors within the academy: An ethical dilemma or not? [Doctoral dissertation, University of St. Thomas].

https://tinyurl.com/y4dyvrcu

Binder, J. F., Baguley, T., Crook, C., & Miller, F. (2015). The academic value of internships: Benefits across disciplines and student backgrounds. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 73–82.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.12.001

Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices for contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43, 317–324.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

Boskamp, E. (2023, June 19). 20+ compelling internship statistics [2023]: Do interns get paid? Zippia: The Career Expert.

https://www.zippia.com/advice/internship-statistics

Bussell, H., & Forbes, D. (2002). Understanding the volunteer market: The what, where, who, and why of volunteering. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 7(3), 244–257.

https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.183

Chiarelli-Helminiak, C. M., McDonald, K. W., Tower, L. E., Hodge, D. M., & Faul, A. C. (2022). Burnout among social work educators: An eco-logical systems perspective. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 32(7), 931–950.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2021.1977209

Coker, L. (2009). Legal implications of unpaid internships. Employee Relations Law Journal, 35(3), 35–39.

https://tinyurl.com/4v3xv4xy

Council on Social Work Education (2008). 2008 educational policy and accreditation standards.

https://tinyurl.com/5fm78d6s

Council on Social Work Education (2021). Statistics on social work education in the United States.

https://tinyurl.com/3v2crzcj

Council on Social Work Education (2022). 2022 educational policy and accreditation standards.

https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/policies-process/2022epas/

Crain, A. (2016). Understanding the impact of unpaid internships on college student career development and employment outcomes. NACE Foundation.

https://ebiztest.naceweb.org/uploadedfiles/files/2016/guide/the-impact-of-unpaid-internships-on-career-development.pdf

de Bie, A., Chaplin, J., Vengris, J., Dagnachew, E., & Jackson, R. (2021). Not “everything’s a learning experience”: Racialized, Indigenous, 2SLGBTQ, and disabled students in social work field placements. Social Work Education, 40(6), 756–772.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1843614

Dill, K., Aguilera, N. B., Graham, W. K., & Voss, T. (2023). Paid internships: A review of the literature. Field Educator, 13(2).

https://tinyurl.com/55nns7r3

Eisenbrey, R. (2012, Jan. 5). Unpaid internships hurt mobility. Economic Policy Institute.

https://www.epi.org/blog/unpaid-internships-economic-mobility/

Ellison, M. L., & Raskin, M. S. (2014). Mentoring field directors: A national exploratory study. Journal of Social Work Education, 50(1), 70–83.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.856231

Fennell, A. (2023, June). Internship statistics U.S. 2023. StandOutCV.

https://www.standout-cv.com/usa/internship-statistics#unpaid-percentage

Finch, D. J., Hamilton, L. K., Baldwin, R., & Zehner, M. (2013). An exploratory survey of factors affecting undergraduate employability. Education & Training, 55(7), 681–704.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2012-0077

Forbes Human Resources Council (2022, Aug. 12). The importance of internships and the invaluable relationships they bring.

https://tinyurl.com/ycezvdpp

Gardner, P. (2010). The debate over unpaid college internships. Intern Bridge.

https://tinyurl.com/36rknc3h

Gault, J., Leach, E., & Duey, M. (2010). Effects of business internships on job marketability: The employers’ perspective. Education & Training, 52(1), 76–88.

https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011017690

Grise-Owens, E., Miller, J., Esobar-Ratliff, L., Addison, D., Marshall, M., & Traube, D. (2016). A field practicum experience in designing and developing a wellness initiative: An agency and university partnership. Field Educator, 6(2), 1–19.

https://tinyurl.com/ym78wnv2

Guarise, D., & Kostenblatt, J. (2018). The impact of unpaid internships on the career success of liberal arts graduates. NACE Center.

https://tinyurl.com/23s46ykc

Hager, M. A., & Brudney, J. L. (2004). Volunteer management: Practices and retention of volunteers. The Urban Institute.

https://tinyurl.com/574tn95x

Hodge, L., Oke, N., McIntyre, H., & Turner, S. (2021). Lengthy unpaid placements in social work: The impacts on student well-being. Social Work Education, 40(6), 787–802.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1736542

Holcomb, D. (2024). Social work departmental leadership attitudes on formal mentorship: Impact on field directors. Field Educator, 14(1).

https://tinyurl.com/35zzh5vs

Huhman, H. R. (2024). The evolution of the internship. Undercover Recruiter.

https://www.theundercoverrecruiter.com/internship-evolution/

Jerrim, J., & de Vries, R. (2017). The limitations of quantitative social science for informing public policy. Evidence & Policy, 13(1), 117–133.

https://doi.org/10.1332/174426415X14431000856662

Johnson, N., Archibald, P., Estreet, A., & Morgan, A. (2021). The cost of being Black in social work practicum. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3).

https://doi.org/10.18060/24115

Judge, T. A,, Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376

Lager, P. B., & Robbins, V. C. (2004). Guest editorial—Field education: Exploring the future, expanding the vision. Journal of Social Work Education, 40(1), 3–12.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2004.10778475

Lynch, M., Stalker, K., & McClain-Meeder, K. (2023). Emerging best practices for employment-based field placements: A path to a more equitable field experience. Field Educator, 13(2).

https://tinyurl.com/6dwhb2r4

Lyter, S. C. (2012). Potential of field education as signature pedagogy: The field director role. Journal of Social Work Education, 48(1), 179–188.

https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2012.201000005

McHugh, P. P. (2017). The impact of compensation, supervision, and work design on internship efficacy: Implications for educators, employers, and prospective interns. Journal of Education and Work, 30(4), 367–382.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2016.1181729

Moran, T. (2013). Study of interns’ perceptions of satisfaction with experiential learning (Publication No. 3611373) [Doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED565969

Morgado, F. F. R., Meireles, J. F. F., Neves, C. M., Amaral, A. C. S., & Ferreira, M. E. C. (2017). Scale development: Ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crĭtica, 30(3).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0057-1

Morris, L. (2023). Looking a gift horse in the mouth: Working students under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Washington & Lee Law Review, 80(1), 445–538.

https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol80/iss1/9

National Association of Colleges and Employers (2019). The 2019 student survey report: Attitudes and preferences of bachelor’s degree students at four-year schools.

https://tinyurl.com/y83a4ecj

National Association of Colleges and Employers (2023). NACE internship survey and compensation guide.

https://www.naceweb.org/store/2023/internship-survey-compensation-guide-combo/

National Association of Social Workers—Illinois Chapter (2024). NASW-IL policy position statement on compensated practicum education.

https://www.naswil.org/post/nasw-il-policy-position-statement-on-compensated-practicum-education

National Association of Social Workers—Massachusetts Chapter (2024). SUPER Act.

https://www.naswma.org/page/SUPERAct

National Association of Social Workers—Ohio Chapter (2024). Campaign for paid internships.

https://www.naswoh.org/page/paidinternships

National Survey of College Internships (2021). National Survey of College Internships (NSCI) 2021 report.

https://ccwt.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/CCWT_NSCI-2021-Report.pdf

Porter, R. (2019, August 26). How important are internships and co-ops? College Recruiter.

https://www.collegerecruiter.com/blog/2019/08/26/how-important-are-internships-and-co-ops

Roggow, M. (2014). Strengthening community colleges through institutional collaborations. Jossey-Bass.

Rothschild, P. C., & Rothschild, C. L. (2020). The unpaid internship: Benefits, drawbacks, and legal issues. Administrative Issues Journal, 10(2), 1–17.

https://tinyurl.com/5n6nfbsd

Shethji, P., & Mayo, L. (2011). Perspectives: Reducing internship inequity. Diverse: Issues in Higher Education.

https://tinyurl.com/yvk4d4a3

Skeen, A. (2022). The conversation: Paid versus unpaid field placements. Field Educator, 12(2).

https://tinyurl.com/45tvedj8

Stack, K., & Fede, J. (2017, Aug. 1). Internships as a pedagogical approach to soft-skill development. National Association of Colleges and Employers.

https://tinyurl.com/bdf6n7wj

Svacina, L. S. (2012). A review of research on unpaid internship legal issues: Implications for career service professionals. Journal of Cooperative Education & Internships, 46(1), 77–87.

https://wilresearch.uwaterloo.ca/Resource/View/1703

Waxman, O. R. (2018, July 25). How internships replaced the entry-level job. Time.

https://www.time.com/5342599/history-of-interns-internships/

Wayne, J., Bogo, M., & Raskin, M. (2010). Field education as the signature pedagogy of social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(3), 327–339.

https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2010.200900043

Wertheimer, M. R., & Sodhi, M. (2014). Beyond field education: Leadership of field directors. Journal of Social Work Education, 50(1), 48–38.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.856230

Yamada, D. (2016). The legal and social movement against unpaid internships. Northeastern University Law Journal, 8(2), 357–396.

https://tinyurl.com/4r3jd9ff

Zilvinskis, J., Gillis, J., & Smith, K. K. (2020). Unpaid versus paid internships: Group membership makes the difference. Journal of College Student Development, 61(4), 510–516.

https://www.doi.org/10.1353/csd.2020.0042